Tattooed Heroes of Edo Period Japan

Tattoos: Ritual. Identity. Obsession. Art is an exhibition in the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) coming from Museé du quai Branly, Paris. It explores 5000 years of tattoo tradition around the world. The traditional and contemporary tattoos of Japan are featured prominently in their own section of the exhibition. This article introduces several tattoo images, some of which are not covered in the exhibition.

After the establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1603, years of civil warfare in Japan came to an end. As peace settled over Japan the samurai class no longer performed the same roles they previously held. During the reign of the fifth shogun Tsunayoshio (1646-1709) military inspection could not be held because the samurai no longer habitually carried weapons. The samurai class that was once highly regarded for its chivalry and moral code was now seen as corrupt by the people. The samurai class had fallen from grace in the eyes of the public and Edo period Japan needed a new group of heroes to fill the void. Otokodate or ‘street knights’ readily filled the physical and conceptual role. Otokodate were usually heavily tattooed young men aiding people who were dealt with unjustly by the samurai. Edo period warrior prints, notably the One Hundred and Eight Heroes of Popular Suikoden by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), were widely circulated. Suikoden, a Japanese translation of a Ming Dynasty classical novel revolves around the brave accomplishments of 108 Robin Hood-type heroes. This theme was popular in Edo for the same reason it was popular in Ming China - public dissatisfaction with the government. The characters in Suikoden often portrayed the otokodate, spurring a surge in the popularity of warrior prints during the Edo period.

Figure 1: “Shōsharan Bokushun and Byōtaichū Setsuei” from The 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden; Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861); Oban format paper; woodblock printed; Edo period; c.1827-1830; 2009.124.58; Gift of Professor James King; Length 36.5 cm; Width 24.7 cm (ROM Photography)

Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s One Hundred and Eight Heroes of Popular Suikoden is arguably the most popular series of warrior prints of the Edo period. Kuniyoshi’s fascination with the imagery and symbolisms of tattoos and heroism can be seen in the notable difference between the novel and Kuniyoshi’s images: only six of Suikoden’s characters are described to have tattoos but fifteen heroes are depicted with tattoo by Kuniyoshi. For example, in his work Shosharan Bokushan and Boytaichu Setsuei (Figure 1), Setsuei’s tattoos were not mentioned in the tale. Setsuei is depicted with tattoos because his character fits the ideal of an otokodate. In this print, Setsuei is engaged in a fight with Bokushan. The story tells of Setsuei, a medicine peddler who unintentionally disrespected Bokushan, a martial art master from an influential and wealthy family. Bokushan retaliated by forbidding the townsmen from purchasing medicine from Setsuei. One day, a man named Song Jiang pays Setsuei for his service and in doing so infuriates Bokushan. Bokushan’s intent to harm Song Jiang was prevented by the heroic Setsuei. With his physical appearance, story of humble origins, and bravery in standing up against a higher authority Setsuei exemplifies the venerable otokodate. If the character of Setsuei represents the otokodate in Edo period society, then Bokushan’s character would represent the samurai class.

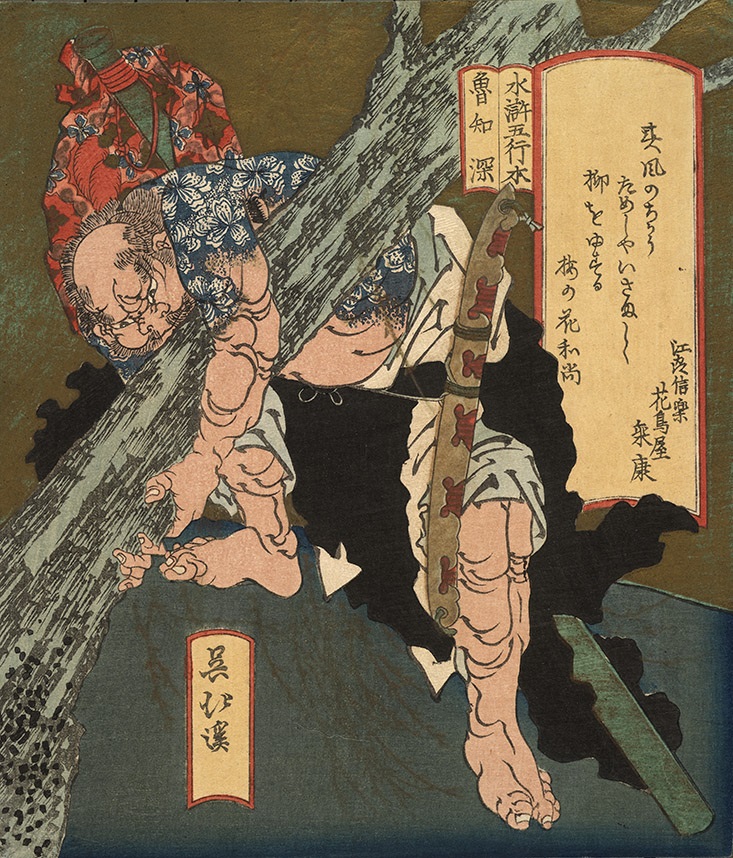

Figure 2: “Group A Copy” of Kaosho Rochishin from The Five Elements in the Suikoden; Totoya Hokkei (1780-1850); Shikishiban format paper; surimono; woodblock-printed; Japan: 19th century; ca. 1890s; 2009.124.43; Gift of Professor James King; Height 21.0 cm; Width 18.0 cm (ROM photography)

The character of Kaosho Rochishin from Suikoden is popularly known as the ‘floral monk’ because of the cherry blossom tattoo that adorns his upper body. The ROM’s collection has two prints depicting this character: a print by Totoya Hokkei and another print by an anonymous artist. Group A copy of Kaoshō Rochishin (Figure 2) shows a famous scene from Suikoden where the floral monk is uprooting a willow tree to scare off crows that were harassing his gang of thieves. Kaoshō Rochishin (displayed in Tattoos: Ritual. Identity. Obsession. Art) illustrates an example of an erotic print inspired by warriors from Suikoden. According to the preface to a 17th century erotic book, Amusements of Warriors on the Eve of Battle, the relationship between making love and making war is closely linked. The text on this print reads, “He was a strong and lecherous man. He has raised many eyebrows by attacking a woman with willow-shaped hips.” As mentioned, Rochishin was known for uprooting a willow tree. The interplay of poetry between a woman’s body and a tree provide a glimpse to the culture of the Edo period dominated by the middle and lower class of society.

Figure 3: “Roshi Ensei” from The 108 Heroes of the Popular Tale of Suikoden; Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861); Vertical Oban format paper; woodblock-printed; Japan: Edo period; ca. 1827-1830; 926.18.1032; Sir Edmund Walker Collection; Height 37.5 cm; Width 26.2 cm (ROM photography)

Another print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi illustrates Roshi Ensei, a character from Suikoden with his body adorned with peonies and Chinese guardian lion motifs. In this print (Figure 3) Ensei is depicted holding a thick pole that is covered with cloth at the very moment he defeats a champion wrestler, seen here underneath Ensei’s feet. The champion wrestler is described as a large proud man filled with arrogance due to his status as undefeated champion for two years. The arrogant wrestler could be seen as the impregnable upper class of Edo-period Japan, namely the samurai class, while Ensei’s character represents the underdog of society unveiled to be the true hero.

Figure 4: “People of Three Occupations Got Drunk” from Ansei Ni Otsu-u nen Daijishin-e; Anonymous; Ink and colour on paper; Japan: Edo period; ca. 1855-1856; 2004.38.1; Acquisition with the Louise Hawley Stone Charitable Trust; Height 37.3 cm; Width 28.0 cm (ROM photography)

Figure 5: “Tug-of-War Between Namazu and the God Kashima” from Ansei Ni Otsu-u nen Daijishin-e; Anonymous; Ink and colour on paper; Japan: Edo period; ca. 1855-1856; 2004.38.1; Acquisition with the Louise Hawley Stone Charitable Trust; Height 30.2 cm; Width 35.8 cm (ROM photography)

The Ansei Edo Earthquake woodblock print is a unique album in the ROM’s collection. It is one of a kind as the original collector bound the prints himself and added his own preface to it. There were positive and negative outcomes of the 1855 earthquake for those in Edo, depending on one’s occupation. After the disaster, occupations like fire fighting, construction, and news publication thrived while the prostitutes whose brothels in the Yoshiwara Entertainment District were destroyed by the earthquake found themselves on the receiving end of the short end of the stick. The social conflict between the two groups is illustrated in these earthquake prints. In People of Three Occupations Got Drunk (Figure 4), a prostitute and the man on the left are depicted as distressed and angry while the tattooed man in the middle appears to be laughing joyfully. The association between tattooed men and fire-fighters are not uncommon as fire-fighters without tattoos were a rare occurrence in that time. An Edo fireman even had a phrase tattooed on his body illustrating the relationship, “Although it may be considered as a preposterous motto, the union of firemen must be tattooed.” Tug-of-War Between Namazu and the God Kashima (Figure 5) illustrates the tension between the two groups of occupations. According to legend, the god Kashima is believed to control namazu, the catfish believed in folklore to avert earthquakes. In this print, the group of people supporting god Kashima includes the samurai class and prostitutes while one of the supporters of namazu is a tattooed man, presumably a fire-fighter.

This blog was prepared by Su Yen Chong, an Art History undergraduate student at the University of Toronto and an intern at the ROM, edited by Josiah Ariyama and Joachim von Rosen under the supervision of Dr. Asato Ikeda.