Interview with Dale Chihuly

Guest blog by Douglas Thomson, Content Manager ROM Magazine

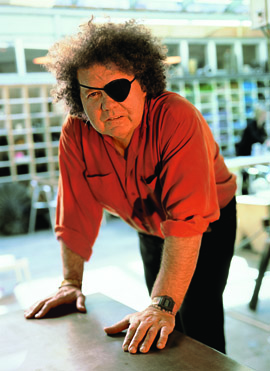

Sculptor Dale Chihuly pushes artistic boundaries, using heat, human breath, gravity, and glass as his creative tools.

CHIHULY, an exhibition by American sculptor Dale Chihuly, is set to open at the ROM on June 25. As an artist, Chihuly is renowned for transforming glass-blowing from a craft to a fine art and is regarded as the “Tiffany” of our day. Chihuly is perhaps best known for his ambitious architectural installations in public spaces and exhibitions that have been presented in more than 250 museums and gardens worldwide. With heat, gravity, human breath, and centrifugal force as his tools, Chihuly continues to push the boundaries of the medium of glass in terms of colour, form, scale, and light. We recently had a chance to meet the artist as he prepared for his ROM exhibition and ask him a few questions about his spectacular work…

There are several spectacular pieces coming for the ROM's CHIHULY exhibition, do you have a favourite?

I don’t really have one particular favourite series or installation. I’m an avid collector and do have a rather large collection of northwest woven baskets and woollen trade blankets, several of which will be on display in one of the installations we call the “Northwest Room.”

Does the technique of creating a work differ from work to work? Or are they all made using the same basic technique?

I don’t use a lot of tools. Just human breath, centrifugal force, gravity, and fire to make the glass. This wondrous event of blowing human air down a blowpipe and out comes this amazing form.

If you weren't creating with glass, what alternative career might you pursue?

If I hadn’t become an artist I think I would have liked to have become an architect. I’ve always been an admirer of architecture. It’s something that as an artist, when assessing a space or landscape for an installation of my work, I always take into consideration.

What drew you to working with glass? Do you enjoy other type of creative work?

While incorporating glass into weavings in a course at the University of Washington, I also developed a way to melt and fuse the pieces of coloured glass together with copper wire, which I could then weave into the fabric. One night, I melted a few pounds of stained glass in one of my kilns and dipped a steel pipe into it. I blew into the pipe and a bubble of glass appeared. I had never seen glass-blowing before. My fascination with it probably comes in part from discovering the process that night by accident. From that moment, I became obsessed with learning all I could about glass.

As far as other creative types of work…somebody once said that people become artists because they have a certain kind of energy to release. That rings true to me. It must have an outlet. That’s why I draw. I originally started drawing as a means of communicating ideas to the team, and now they have evolved into a creative and energetic release for me.

Has the technology of glass-blowing changed since you began your career? To an outsider it looks like a pretty ancient art.

I was the first glass-blower, I think, from the United States to go work in Venice. I wrote letters to all the factories in Italy and got one favourable letter back from Ludovico de Santillana from the Venini Factory on the Island of Murano. It was there, when I immersed myself in the Italian tradition, that I really learned about glass-blowing and working with a team. The basic skills and tools have not changed very much; it’s more a matter of how you apply the techniques. I then returned to the United States and started the glass program at the Rhode Island School of Design, which is the oldest and largest art school in the United States. In 1971, through the generosity of patrons Anne Gould Hauberg and John Hauberg, we co-founded the Pilchuck Glass School, which has since grown into the world’s most comprehensive centre for glass-arts education in the world. The fact that there are now more glass-blowers in the Northwest than in Venice because of these historic milestones is wonderful and very gratifying—something I could have never imagined.

How much time do you spend in an average week creating? Do you have set work periods, or are your creative sessions a response to inspiration?

I’m always creating or thinking about what I want to create. I respond to inspiration as it comes and, fortunately for me, I am inspired by many things.

Do you have any favourite works on your agenda? is it something you might be able to tell us a bit about?

Who knows what’s next. When people say what are you going to do next, I always say, “If I knew what I was going to do next I’d be doing it.”

Are there works coming to Toronto that haven't been shown before?

I design all of my shows for each location, so in a sense every installation will be seen in a new light; however, I am doing an installation of icicles that has never been seen before. I’m also creating a new large-scale work for the Museum atrium.

Have you ever designed a project that just didn't work out? That is, it was impossible to actually build.

I’m always pushing the boundaries of the medium in terms of colour, form, scale, and light. The whole idea of making art, as far as I’m concerned, comes from doing it over and over and over. You have to make a lot of mistakes. Mistakes made in glass-blowing can become some of the most beautiful artworks. For me, it’s about following your gut and creating something no one has seen before.

Tell us more about the inspirations for your work.

I work from my gut. I just work, and out it comes. I don’t know what it is until it’s finished, and I often title a piece after it’s done. Call it chance, call it fate. I want to make something that has never been made before, something no one has ever seen, something with power that inspires everyone who sees it, creating an unforgettable experience.

What is your ambition for the art of glass-blowing? Where would you like this art/craft to go?

Glass has a lot of durability, but it’s also fragile and can break at any moment. I’ve always tried to push the medium as far as I could in terms of shape and scale. There are very few materials that react as much as glass does.

What would you like people to take away after seeing your work?

My hope with my artwork and exhibitions around the world is that people have the opportunity to experience and enjoy them.

Originally published in the Summer 2016 issue of the ROM Magazine.