Douglas Coupland: Everything Man

Artist, writer, thinker

Douglas Coupland is a man of many talents

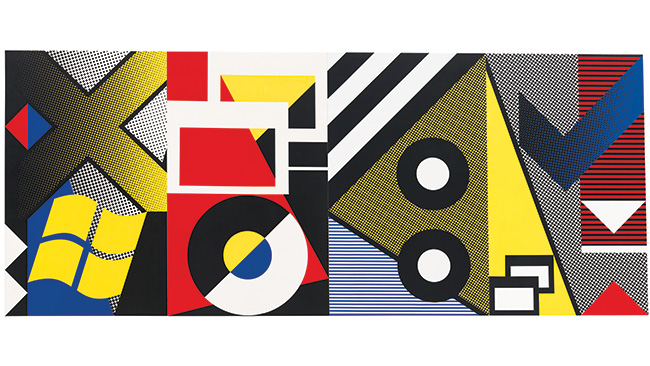

Douglas Coupland is a Canadian novelist and artist. Although it was his work as a fiction writer that Coupland was first recognized for, his writing is complemented by his work in design and visual art, which arises from his early formal training. His first novel was the 1991 international bestseller Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. He has published 13 novels, two collections of short stories, and eight non-fiction books. The exhibition, entitled everywhere is anywhere is anything is everything is a major survey of Coupland’s visual art.

AW: Hi Doug, we can’t wait for your show to open at the ROM and MOCCA [Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art].

Most people are not aware that before you embarked on your writing career, you studied art and design. In the 1990s you focused on your writing, and in 2000 you returned to visual art. You have just published your recent non-fiction book Kitten Clone: Inside Alcatel-Lucent. How do you juggle a busy writing practice with making art?

DC: Art takes place in space and writing takes place in time. In writing you have fiction and non-fiction, and in art you have private art and public art. Those are the four quadrants of my creative life. I find that I am happiest when I have something happening in all four quadrants, which means that all parts of my brain are getting used. At the moment the only thing I am not doing is working on a novel, and I can really feel that. For me, it’s trying to make the most of being alive, in those four forms.

AW: It sounds like a balancing act, but it’s something that you obviously need to do as a creative thinker, something you need to do on a daily basis.

DC: Oh—I agree, and also each aspect informs the other. For example the book Kitten Clone—writing it opened an astonishing number of doors—creative doors, fiction doors, non-fiction doors. These activities are not necessarily isolated from each other. They all feed into it and from each other. It’s not like each exists on a separate asteroid and they are not in communication with each other.

AW: Why did you return to making art? At one point in your life—it seems the two practices were quite separate—and now they seem to be quite integrated. So, what made you return to artmaking?

DC: Looking back, I am very fortunate that UBC keeps all my archives. I look across the 1990s, and while yes I was writing, there was actually an astonishing amount of visual work going on then. I was at the right time in the right place, starting with Wired magazine in 1992. I worked in downtown San Francisco and in Palo Alto, where it was all happening. Back then there wasn’t any Flash and Photoshop. It was all very, very primitive, and so any of the visuals that we used online had to be made in hard copy first—collaging, sometimes using Letraset. There was definitely a zine aesthetic going on.

You can look at the archives from the 1990s and you can see that there was a visual evolution, which is definitely the Doug sensibility that sort of mirrored the rise of the technology. And then there were all those book tours I was doing. Part of staying sane on the road is that I was also doing a daily diary and daily collages—making hundreds and hundreds of them. It was not the complete abandonment of the visual. It was pioneering the essence of the new way of looking at things. It was not a complete negation.

AW: I think that’s important for people to know, because I think most people know you as a writer and perhaps are less familiar with your art practice. I believe this exhibition of your artwork is important because it reveals and brings all facets of your practice and thinking together in a really nice way.

I know you said that art takes place in space and writing takes place in time. But, how would you describe the difference, if you think there is a difference, between writing a novel and working with materials and objects to make art?

DC: Each activity creates a certain sensation in the brain. When writing is going well, it’s like a high, it’s like a drug, and it makes me feel a very certain predictable way, the way alcohol does. And, when making things with my hands and being in the studio, it’s like another very, very reliable sensation. It creates a very specific and repeatable sensation in my brain.

Short-form fiction, I love, it is my quiet place, my happy place. Every form of creative activity creates its own repeatable brain sensation. I just like that. You can slow it down to brain chemistry or pathology, and that is one of the great questions of our day, where does brain damage begin and where does personality end and vice versa. Where does personality end and brain damage begin—that’s one of the slogans.

AW: Is that one of your slogans?

DC: It is. It’s Marshall McLuhan basically. Which is the riddle of his brain.

AW: I am interested in your connection to pop culture and Andy Warhol. I was reading about Ai Wei Wei recently, in Sarah Thornton’s book 33 Artists in 3 Acts. In the book he mentions that the The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B & Back Again was a big influence on him as an aspiring artist. And, I know it was one of the books that inspired you. So, this reference to Warhol is interesting to me because we recently had Bob Colacello, who worked closely with Warhol, speak at the ROM about Warhol as a change maker. Why do you think Warhol is such an influence on artists and more broadly on contemporary culture?

DC: Before I read From A to B & Back Again, I would have been eight and looking in the World Book Encyclopedia, probably 69th or 70th edition. I guess I was looking at something else in P and found Pop Art, and thought, what’s this? They had a Warhol soup can and a Blam painting by Lichtenstein and I looked at that and said, “That’s it! That’s for me.” And I think what Pop does, what it did for me, for Ai Wei Wei, and for a lot of people, is that it allows you to look at the world in a certain way and suddenly almost everything becomes aesthetic. I think a lot of what art does—even Jeff Wall’s work—he takes certain parts of the world that you’d never thought of as being beautiful or aesthetic before and suddenly it is. I always think it’s one aspect of what any art—visual or verbal can do.

I hope I am not jumping the gun here by saying that in the Vancouver show there are endless numbers of kids in their 20s and 30s coming in. In the catalogue we talked about utopias, what is utopia, and what was happening in the show in Vancouver, and what I hope happens again in Toronto, is that it unwittingly created a utopia. Where all these impressions, sensations, and visual images which people had in their brains suddenly were rearranged in something new in life that wasn’t necessarily aesthetic, and you can look at it as say “wow that actually is kind of beautiful.”

AW: Well to me, that’s what artists do, they show us our world anew. They show us the obvious things in a new way that gives us something to think about. I understand you collect lots of things. A new work in the exhibition is The Brain, which is composed of hundreds of objects you have collected—it’s like a cabinet of curiosities—do you see it as a visual biography?

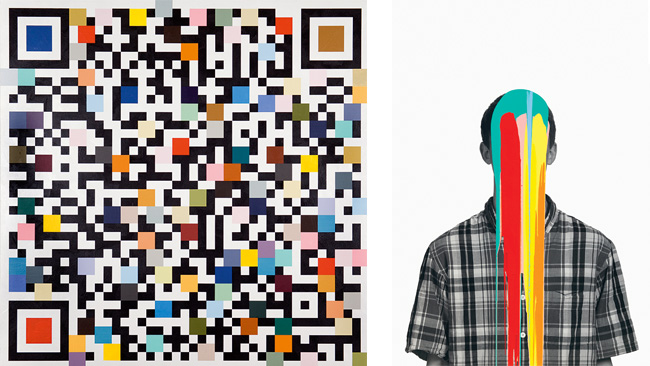

DC: I see it as a work in progress. Anyone’s brain is a work in progress. At any given moment, your brain cells are dying and new ones being formed. Brains can change on a dime; you take a wrong drug, you take a good drug. Our brains are dynamic and always in motion. Of all the pieces in the show, that’s the one that won’t be resolved because my brain won’t be resolved until I die and that will be its final version. I sound like a broken record on the subject. But, if you have an impulse to collect something, whether it is plastic bottle caps or art or books, or whatever, give in to that impulse as much as you can—and do it without over-thinking it and very, very quickly it will probably tell you something about yourself that is very deep and you maybe weren’t even aware of—and that’s the magic of collecting. It’s about learning things about yourself that you’d never otherwise would know.

So with The Brain, I was collecting, not over-thinking it for about 15 years. Objects that just happen to have a bit of resonance, it did not have to be much. And then I just put it all in boxes, 165 in the end. And then sorted it all out and tried to make some sense of it. This is what happens with the art I collect. And, with my writing, I have notepads. It drives people crazy, I pull out my notepad and jot down ideas. You can collect ideas, objects, art, you can collect anything really.

AW: Much of your work—both your writing and artwork—deals with the impact of technology on humanity. One of your slogan works is “I miss my pre-internet brain.” What does this say about your relationship to technology?

DC: Well, There are two side effects of technology: the intended effects and the unintended effects. The thing with technology is that you make it, and then it makes you. It’s not like a one-way street. Some people call technology “alienating,” but that is not true because aliens did not come down from outer space and hand all this stuff to us. It was made by humans and as such it can only ever bring out manifestations of our humanity.

You have tribes where everybody has full body tattoos or earrings or whatever; instead of having full body tattoos, we have these tattooed brains that have been shaped by technology, so we are not very different in that way.

AW: You have referred to our contemporary time as accelerated, and in your recent book you wonder what connectivity is doing to our brains and our sense of being as humans. What role do you see a museum such as the ROM playing in contemporary society?

DC: I don’t think it should just be a game of playing catch-up. I think that it would be very interesting and it would be creative for any institution, rather than being passive, to instead be active and try to harness the changes going on in culture. I think we have so many great tools for allowing visitors to the gallery to reinterpret the experience, to remember it, to keep it, to share it. If you can facilitate that progress, it would be a tick in the right box for the institution.

AW: If the museum is about the collection and the preservation of memory, what do you think about how the museum preserves memory in our society? Do you think memory is at risk?

DC: I have a box filled with blue 56J floppy discs from the 1990s in my office. I guess some would be 20 years old at this point. So I got a floppy disk reader and I linked it up by USB cable to my computer, and only half the files on the discs are readable. I guess electrons are evaporating off the magnetic surface, and once they are gone they are gone. This is creating a huge issue in the world of archiving. How do you keep something evanescent, how do you make it concrete and permanent? I remember growing up with a wicker basket filled with bags of snapshots, and it always sat next to the land-line telephone, and while you were talking to people on the phone you’d look at pictures of someone at a party or in a canoe or what have you. We’ve lost that physicality for the longest amount of time. In the course of a day you see thousands if not tens of thousands of .jpgs. You actually see very few, concrete, tangible images.

The older archivists are hoping to retire so they won’t have to deal with it. I know the younger curators and archivists are chafing at the bit to get into it and trying to figure out how this is all going to work. We might not have that much record of it in the end, that’s the strange thing. And now we have the cloud, and wow, what is it? How permanent is it? You know that really bad picture of you at a party, in the old days it would have been a snapshot, but now it’s out there in the cloud. Will it be there forever? Will it get vanished? Will it get hijacked? Who knows? Oh boy.

AW: You refer to your practices of writing and making art as ways of perceiving and experiencing the world. What do you want people to take away from this exhibition?

DC: It might be something along the lines of: “Oh wait, you feel the same way too?” It’s this massive reconfiguration of our being happening in technology now. Don’t forget, we are having more technology thrown at us faster than absolutely ever in the history of history. We are actually doing this with some grace and some intelligence. All these weird perceptions that you thought only you were having, everyone on Earth is having them, everyone. This is the first time since the last ice age we have this commonality of experience, this commonality of data/ the cloud we can tap into. Everyone knows everything. That’s new. Now that we know everything, or now that we can know everything, where are we going to take that? What are we going to do with it? What are we going to create?

AW: You know what I think is so fantastic about your being an observer of contemporary life, your commenting about our technological age, is that through your artwork—which is very tactile and object based—you are using this non-technological form to inform us about our age.

DC: I was recently in Brazil for the Bienal de São Paulo. And, the curator there, Marcello Dantas, said, “Douglas, you are not actually a contemporary artist, as you are more an artist of the contemporary.” It works for me.

Originally published in ROM Magazine, Winter 2015.