Every Thursday at 10 am on Instagram we chat with a different ROM expert ready to answer your burning questions on a different subject. This time on Ask ROM Anything we are talking to Arlene Gehmacher, curator of Canadian Art at the ROM. Arlene’s research at the ROM is primarily collections-based, with several interrelated projects: the history of building the ROM’s Canadian collection, depictions of colonial and settler Canada, and the function of popular imagery through works by illustrators such as Rex Woods.

While working from home during the Museum’s closure, Arlene is completing the critical essay and catalogue of ROM’s collection of Canadian watercolours and drawings, as well as acquisitions. She will soon shift her focus to Forster’s Canadian national portrait gallery.

Q. Does Canadian art also include Indigenous art, and if so, what proportion of the collection?

A. At the ROM, artwork by Indigenous, Metis, and Inuit artists historically has been collected and curated by the Anthropology section of the department of World Art & Culture, and that approach has largely continued to the present time. At the ROM, “Candian art” has been understood more in terms of cultural production by colonial and settler societies. That said, with their permission, I did include in the Sigmund Samuel Gallery of Canada “All Magic is in the Will,” a work by Cree/Metis artists Rebecca and Kenny Baird. It is in the “Canada Reimagined” section. I was struck by the implicit tensions between the ethereal, transparent qualities glass, and the reality of the four feathers' weight, also the complementaries of “will” and “magic.” To my mind the piece assumes an eloquent expression of complexities within Canadian society today, including Truth and Reconciliation.

Q. What makes Canadian art unique?

A. I would say context is everything! Early artists in Canada (starting 1700s) had been trained in Europe, so they were adhering to styles of art, e.g. baroque, with which they continued to engage. Artists from Canada in the mid- to late-nineteenth century started to go to Europe, primarily Italy, then France, for their artistic training at academies or private studios. What we as art historians of Canadian art study is not just the subject matter, but also the socio-political forces that drive Canadian artists to think and produce in the way they do. This would be true for the works produced from colonial times to the contemporary.

One relatively recent example would be the work of Joyce Wieland. She spent time in New York City in the 1960s but was much informed by her political and cultural environment while retaining her perspective of what it means to be Canadian. Here is a recent informative, but quirky, take on Wieland: it addresses some of those aspects of her work.

Q. What artist or collection would you like to bring to the ROM next?

A. Would love to be able to tip my hand to specifics, but cannot. Broadly speaking though, I am looking to diversify the collection. The ROM’s Canadian collection was from inception collected on the basis of understanding image making in terms of being “documentary.” That’s a complex term, but basically as the collection was being built, it meant empirical reality as evidenced in images — portraits, landscapes, scenes of daily life, and history. Almost exclusively, those images were produced by white artists supported by the ideals of imperialism. So, we have a lot of work to do ensuring that the stories and perspectives of many more Canadians are included. Karin Jones’ work, “Worn” (2015), a Victorian mourning dress, was purchased after its installation in the Wilson Canadian Heritage Room during the ROM’s “Of Africa” program, was a key acquisition. It addresses, in the artist’s own words, the “presence and absence of Africans in Canada’s historical narrative.” I’ll be interviewing Karin on August 19th through the ROM website, but in the meantime, here’s a link to her website, which includes detail photos of the dress.

Q. What is your favourite from the works of the Group of Seven?

A. I’m going to cheat here a bit, and include Tom Thomson, as he was key to the eventual founding of the Group. (He died in 1917, and the Gof7 was formalized in 1920.) Like so many people, I’m pretty enamoured with "Northern River" (National Gallery of Canada). I find the combination of graphic (the relatively flat “screen” of trees in the foreground) qualities and thick, impasted paint really appealing, because I find I'm always trying to reconcile the one with the other. It keeps me moving through the painting. Apart from that, there may be a sentimental reason: a reproduction of “Northern River” hung in our school art room, so I saw it every day and was intrigued from the start. Apart from Thomson, almost any one of Lawren Harris’s “Above Lake Superior” (Art Gallery of Ontario) is not just visually stunning but resonates for me in its air of transcendence. For this painting, too, I have a clear memory of George Elliot Clarke “reading” this painting. It was as transfixing as the painting.

By the way, the ROM needs a Tom Thomson or Group of Seven work! While their paintings generally speaking work well on the eyes and soul, many of them are also relevant to discussions of Canadian culture. It would be terrific if we could “land” one (pun intended ?).

Q. Have maps been used in Canadian art? Are there any examples in the ROM’s collection?

A. Yes, certainly in modern and contemporary art as a way to investigate notions of place, identity, and memory.

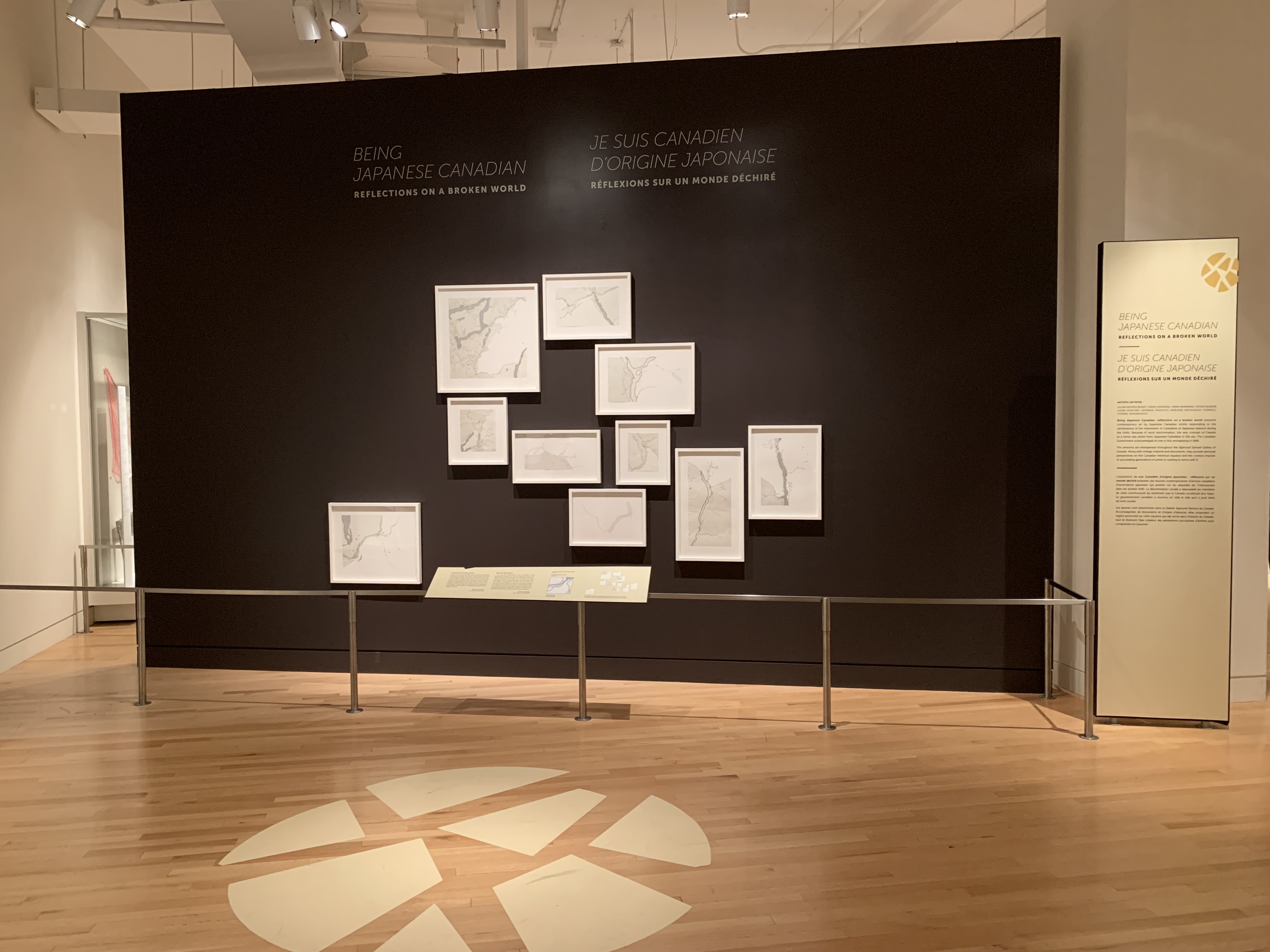

In our exhibit Being Japanese Canadian: reflections on a broken world, one of the works by printmaker Emma Nishimura, a 4th generation Japanese Canadian, used the notion of mapping of delve into and understanding of her own identity as she explored and made sense of her grandparents’ personal history in the context of the unjustified internment of Japanese Canadians in Canada during WWII. In “Constructed Narratives” the artist created maps of the location of Japanese Canadian internment camps, inscribing text from historical accounts of this event to articulate the map markings. The etched series is remarkable, not just for its concept, but also for its presentation, skill, and the deep engagement of the artist so clearly manifest in the work. The ROM ended up purchasing several of the component maps, and Nishimura’s work on this piece continues.

I can direct you to her website, which features a detail of one of the maps. Marvel, enjoy, and reflect.

Q. What is your favourite piece in the ROM’s collection?

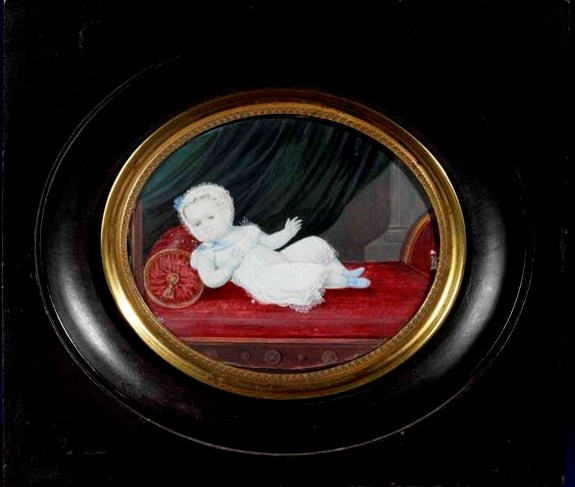

A. As I curator, I often respond to works in the collection from a more distanced position. I am intrigued by so many of the historical watercolours and prints modern illustration art, and contemporary installation works, that my “favourite often becomes what I am immersed in at the moment. But there is one work that I find compelling for so many different reasons: “John McGill Crookshank,” a miniature (watercolour on ivory) from 1824, and thus long before photography was in wide practice. The painting is a portrait of an infant, the epitome of a happy, “gurgling” child. It seems straightforward enough, but research indicates that this is a posthumous portrait. The Crookshank family lived in York (corner of Front and Peter streets) but had business interests in the US (New York and Connecticut). It was during one of their stays in the US that the Crookshank’s first-born died of croup. And suddenly the fascination of research morphs into this painting becoming a “favourite.” The painting is signed “Meucci,” but we don’t know if it’s Antonio Meucci, or his wife Nina, and if gender of artist had an impact on who would paint posthumous portraits. Or what the actual process of commissioning and painting a portrait of deceased beloved child was. When a work raises compelling questions, especially related to intersections of personal and societal histories not just in its own time, but as we can respond to it now, it catapults it into another category for me.

I am also very much taken with the work by Rex Woods. A commercial illustrator, he did much of the cover artwork in the late 1920s, 1930, 1940s for Canadian Home Journal, before moving to Maclean’s in the 1950s. His work for Maclean’s I find particularly compelling to study. I find it laden with irony, and I am currently trying to sort out the hints of subversiveness that I see in some of his work. I have had a visitor pronounce that Rex Woods paintings were better than the Mona Lisa. I respectfully disagree, but his work is of a time, place, and agenda, and he works with his subjects in a way that, if problematic from some perspectives, is nevertheless in terms of social, political an cultural history in Canada, rich, rich, rich.

Q. What is the oldest known piece of Canadian art?

A. I confess, I don’t know the answer to your question! In the context of works produced by colonial and settler societies, though, and in terms of what traditional visual culture studies has brought to the table, it would be the paintings that Roman Catholic religious orders brought over with them starting in the 17th century, not just to keep their own faith, but to try to convert the Indigenous peoples to Christianity. Some of these paintings are votives, often naively-painted images depicting scenes of near-death circumstances or events, such as being shipwrecked: the artist, surviving, would want to give thanks to a greater power through such imagery. Others, such a Frere Luc’s “France carrying the faith to the Hurons of New France” (collection of the Ursuline Convent, Quebec City), are images that were intended to reinforce the agenda of those in power, and as didactic images to explain Christianity. A contemporary (today) reworking/response to this painting is “Les castors du roi” (The King’s Beavers) by Cree artist Kent Monkman. The painting is now in the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

The ROM itself has no paintings of this kind, from this period — it was not an area of interest of Sigmund Samuel, who was the founding collector of ROM’s images of Canadian history.

Q. Who is your favourite contemporary Canadian artist?

A. Honestly, I don’t have a favourite. I’m not just saying that to sidestep the question — as a curator of Canadian art at the ROM, I am looking for different perspectives that address issues relevant to society in Canada. Those issues can run from gender to class to race, but most often within the context of questioning stable concepts of identity.

I find contemporary art that is engaged in those types of questions in creative ways that are thought provoking, is for me a powerful experience. Our recent exhibit Being Japanese Canadian: reflections on a broken world (February-August 2019) opened my eyes to the articulate and passionate work by artists who addressed a very unsettling moment in Canada’s history (invocation by the Canadian government of the War Measures Act to intern/imprison Japanese Canadians solely on the basis of race and ethnic identity). I am aiming to bring more of that into the Canada collection at the ROM.

Q. What do you think the Canadian art scene would look like without government funding?

A. I think art is so deeply embedded in our consciousness that I cannot imagine a lack of funding would do it in completely. I know artists who just feel compelled to create. That said, I know I am grateful that government agencies are in place to help the cause, but also recognize that the art scene relies on a whole complex of organizations and individuals who are learners and appreciators, and they, too, become collaborators to ensure the art scene remains vital.

Q. What happened to Tom Thompson?

A. Your question brings back so many memories! I read “The Mystery of Tom Thomson” voraciously when I was in high school and already on the road wanting to make art history my area of study. I found this CBC blog post hits the nail on the head, in addressing our continued keen interest in Tom Thomson.

Q. How can I get a job working with this collection? I adore it!

A. I am glad you adore the collection. I myself am wholeheartedly engaged with it, and feel really lucky to be able to work with objects day in, day out, researching them, interpreting them from different theoretical viewpoints (which is especially in this era of post-colonial mandates and desires). I think about the collection constantly, how to work with it, how to expand it, how to display it, how to understand the history of its collecting. I kind of live my job as a curator. My own path to this position was through academe — I knew I wanted to be an art historian, and so went for it throughout university. At some point during grad school I knew I wanted to go the full distance, and did do my doctorate in Canadian art (University of Toronto).