Art as Solace

Published

Category

Author

More than a decade after the Afghan war began in 2001

More than a decade after the Afghan war began in 2001, Shamsia Hassani was promulgated to international fame as one of Afghanistan’s first female graffiti artists.

Where the violence of war had scarred Kabul’s buildings, those same abandoned, bombed-out skeletons became a canvas for Hassani to erase memories of war and spray paint dream-like, imaginary worlds with the stylized silhouette of one lone woman at the heart of each mural.

Always depicted with her eyes serenely closed to the world wearing a hijab, a burqa, or other head covering, pressing on the keys of a piano or surrounded by a swarm of bats with cityscapes towering above, Hassani’s murals fast became a humanizing symbol of Afghan women.

Powerful female protagonist

Shown as a contemplative, powerful agent, Hassani’s female protagonist flew in the face of media depictions of Afghan women reduced almost entirely to their sartorial choices or their disempowerment, both by the Taliban and western foreign policy.

On August 15, 2021, after a two-decade-long war, the Taliban reemerged and took over the Afghan government. Since then, Afghan women’s freedoms under the Taliban have eroded significantly. Women have been banned from higher education and government jobs. Beauty parlours have been forced to close. Afghan women have even been banned from visiting the lakes of Band-e-Amir because the Taliban accused them of not wearing their hijabs properly.

Hassani has challenged western stereotypes of Afghan women through her art including western perceptions of the hijab.

“People outside of Afghanistan think that Afghan women are trapped under the burqa, they are not educated, that everyone who puts on a hijab has no freedom. This is simply not true,” she asserts.

Now, Afghanistan is experiencing one of the largest humanitarian refugee crises. Among the many Afghans fractured from their homeland, Hassani presently lives in exile in LA. Her murals have now been destroyed in an Afghanistan radically altered from the one she left.

After I left Kabul, I felt like I died. We Muslims believe that when we die, we go to another world. But your soul is looking for family, friends, and your old life in your home city. I feel like I have died, and I’m searching for my old life.

After I left Kabul, I felt like I died

“After I left Kabul, I felt like I died,” Hassani says, speaking from her LA studio. Unable to return to her home-country for fear of her safety, Hassani’s connection to her beloved Afghanistan is entirely virtual.

“We Muslims believe that when we die, we go to another world. But your soul is looking for family, friends, and your old life in your home city. I feel like I have died, and I’m searching for my old life,” she adds. “Everyone that I know, my friends, my family, everybody is inside my iPad because I’m in touch with them virtually.”

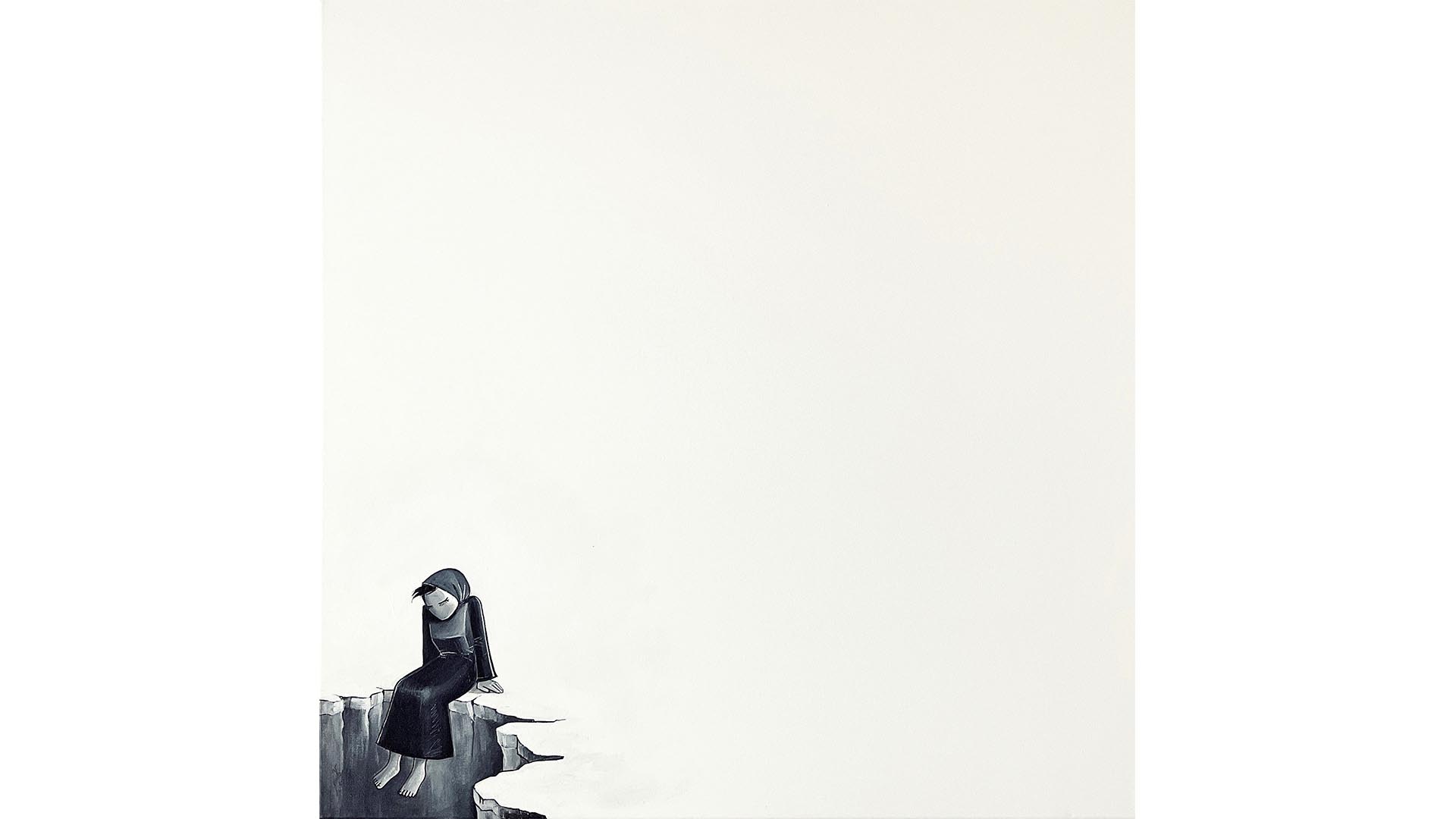

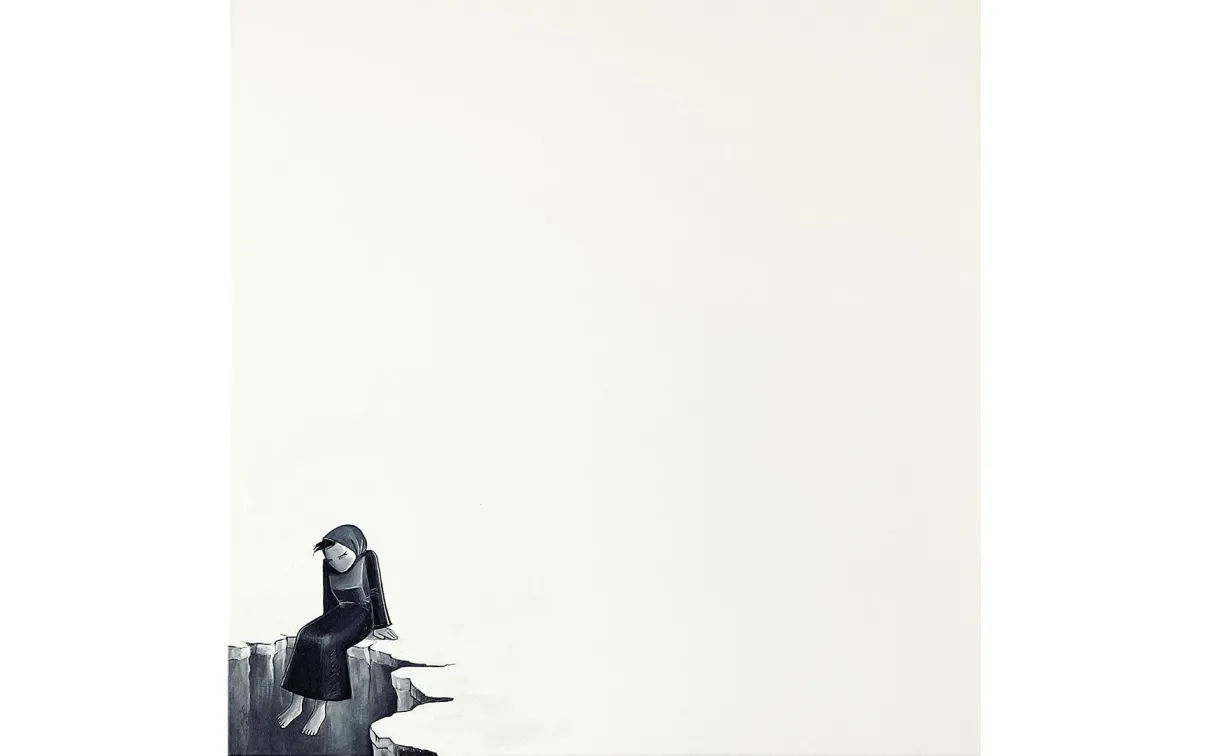

Hassani was specially commissioned to create the work Once Upon a Time/یکی بود یکی نبود (Yeki bood yeki nabood) for ROM’s current exhibition, Being and Belonging: Contemporary Women Artists from the Islamic World and Beyond. The exhibition presents over a hundred works by 25 contemporary women artists born in or connected to a vast geographical region spanning West Africa to Southeast Asia, with many now living in diaspora, including Hassani.

Once Upon a Time is the first artwork the visitor encounters as they walk into the exhibition. The placement was deliberate according to Dr. Fahmida Suleman, ROM’s curator of the Islamic World collections and lead curator of Being and Belonging. “Shamsia’s art encompasses all the themes of the exhibition: being, belonging, space, movement, and power. It also acts as a beacon for visitors who enter the show—imposing in size, contemplative in composition, it asserts that women are formidable agents of change with powerful messages to express,” says Suleman.

In Once Upon a Time, the gravitational force of Hassani’s past pulls her protagonist’s gaze towards a gaping hole in the concrete. Instead of looking towards a vibrantly coloured future, the woman’s gaze is transfixed yearningly towards her roots.

Painted with a pocket made of a Kabul newspaper sheet full of dandelions (symbolizing her hopes and aspirations), the woman can blow on them and make a wish, perhaps to return home someday.

“The figure, she is me, really,” Hassani confesses. “She cannot see her dreams and wishes because she is focusing on her past and looking down,” Hassani says mournfully. “She doesn’t have dreams anymore.”

Gallery

Future Uncertain

The uncertainty of Hassani’s future, and whether she will ever return to Afghanistan has left her drowning in her past, a sentiment reflected in her stylized self-portrait as a figure suspended within a black hole above the concrete.

At the heart of Hassani’s artwork is a female figure depicted without a mouth or nose—a style of illustration adopted by the artist to allow viewers to see themselves in the character. Will she ever paint this woman with her eyes wide open? “I feel this character is a person with her own individual identity,” Hassani says. “If I change her face, she will change into another person.”

Born in Tehran, Iran

Born in Tehran, Iran, to Afghan immigrants, Hassani and her family moved back to Afghanistan in 2004 when she was 16 years old. In her other life as a Fine Arts lecturer at Kabul University, alongside other Afghan creatives, Hassani helped co-found Berang Arts, a contemporary arts organization, in 2009. She also helped launch the first national graffiti festival in Afghanistan. Hassani’s graffiti work has inspired thousands of people around the world, women Afghan artists in particular.

But the despair, longing, and grief Hassani has felt since leaving Afghanistan has provided ample creative fuel.

Being far away from her beloved Kabul, Hassani’s studio in LA has blossomed into an artistic sanctuary where art has become a source of healing, solace and catharsis. Her murals can be found all over the world. Social media, international exhibitions, and workshops have become new vehicles through which she shares her artwork to global audiences.

Creative Process

For Hassani, her creative process always begins by transferring an image she envisions in her mind onto a seemingly insignificant, piece of paper where she focuses all her artistic energies.

“For me, the real artwork is that scrap of paper, because that is the moment in which I pour everything from my heart and mind onto that piece of paper,” Hassani says. “It’s as though I have a big library in my brain, I don’t know which book to take, and then suddenly, I can pick the one that I was always looking for,” she explains.

In the years she lived in Afghanistan, Hassani was optimistic for the country’s future. But her indefinite exile to LA has created a physical separation and yearning—not just between her and her parents, her sister and her friends, but the very walls of Kabul she once painted.

“Although Hassani’s experiences may be specific to Afghan politics and history, her work represents a universal message about how human beings grapple with the concepts of home, belonging, the trauma of forced migration, and the pain of separation from loved ones,” asserts Suleman.

Inspiration and hope

Hassani’s murals and art have infused inspiration and hope into fellow women artists around the world. One wonders, through all her struggles, has she retained some hope for herself?

“I’m trying to maintain hope for myself,” Hassani says, “and to the people of Afghanistan who have migrated to different places and, like me, yearn for their roots and feel hopeless. Even if it’s just for a few seconds, they can look at my art, and briefly forget about their trauma and suffering.”

Aina J. Khan

Aina J. Khan is a London-based freelance journalist who has been published in Al Jazeera English, The Guardian, Vogue Arabia, and VICE.