Inside a journey through the Ecuadorian Amazon to find the largest freshwater scaled fish

Forget fishing for a second.

Because when it comes to bringing big fishes from Ecuador to ROM, catching them is only the beginning. Much more work is needed to keep each specimen from rotting under a blazing sun or being snatched by predators like the black caiman crocodile. Plus, there’s always the risk of losing small but critical tissue samples needed to sequence the species’ DNA and understand their ecology.

Preserving big fishes is especially hard. In fact, Nathan K. Lujan, ROM’s Curator of Fishes, had to spend much of his last trip to the Amazon building various improvised “embalming baths” for specimens too large for their jars, buckets, and barrels. This involved gathering logs, nailing boards, and digging ditches, then lining the pools with plastic and filling them with formaldehyde and river water. That’s to say nothing of all the other gory work with guts, blood, slime, and chemicals needed for preparing a specimen for travel.

All of which begs the question: Why bother? Why risk heat exhaustion, bugs, disease, and chemical burns to bring some dead fishes to a museum?

For Lujan, the answer is simple: scientific discovery—and conservation.

The mystery of the Arapaima

In the struggle to conserve endangered freshwater fishes, knowledge is half the battle. That means understanding the myriad threats fishes face, from dam-driven habitat disruption to overfishing. But it’s just as important to understand the species themselves. And yet, there are many gaps in our collective scientific knowledge, especially of large fishes, many of which weigh over 100kg, making them difficult to transport to places like museums, where they can be classified and studied.

The Arapaima—Earth’s biggest scaled freshwater fish—is the perfect example. Known to locals as paiche in Spanish and pirarucu in Portuguese, the air-breathing Arapaima is a true river monster, which can grow over three metres long and up to 200kg, and lives exclusively in the lowland rivers and lakes of the Amazon and Essequibo river basins in northern South America. While highly desired for food and sport, very little is known about diversity within the genus Arapaima. In fact, for 145 years Arapaima was thought to contain a single species: Arapaima gigas—an assumption that was shattered in 2013, when a new species was described and two old, invalidated species names were resurrected for two morphologically distinct populations. Still, so little is known about Arapaima that its conservation status is listed as "data deficient."

One of the reasons we know so little about this threatened species is because so few specimens and tissues exist. In fact, only one large whole specimen of Arapaima has ever been collected from Ecuador, which scientists from Chicago’s Field Museum found in the 1980s, then returned to Ecuador at the Museum of Biology of the Escuela Politécnica Nacional in Quito. But when Lujan and project leader José Vicente Montoya went to see the specimen earlier this year, it couldn’t be located.

So, as Lujan and Montoya began planning their trip to the Ecuadorian Amazon, they resolved to catch at least two Arapaima: one to leave in Ecuador, another to bring back to ROM.

Exactly if or how they would do this wasn’t certain at the outset. But they prepared as well as they could and set off into the rainforests of eastern Ecuador with colleagues from Ecuador’s Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (INABIO), Universidad de las Americas (UDLA), and Ministry of the Environment.

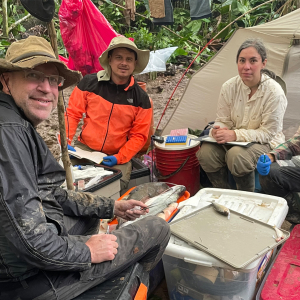

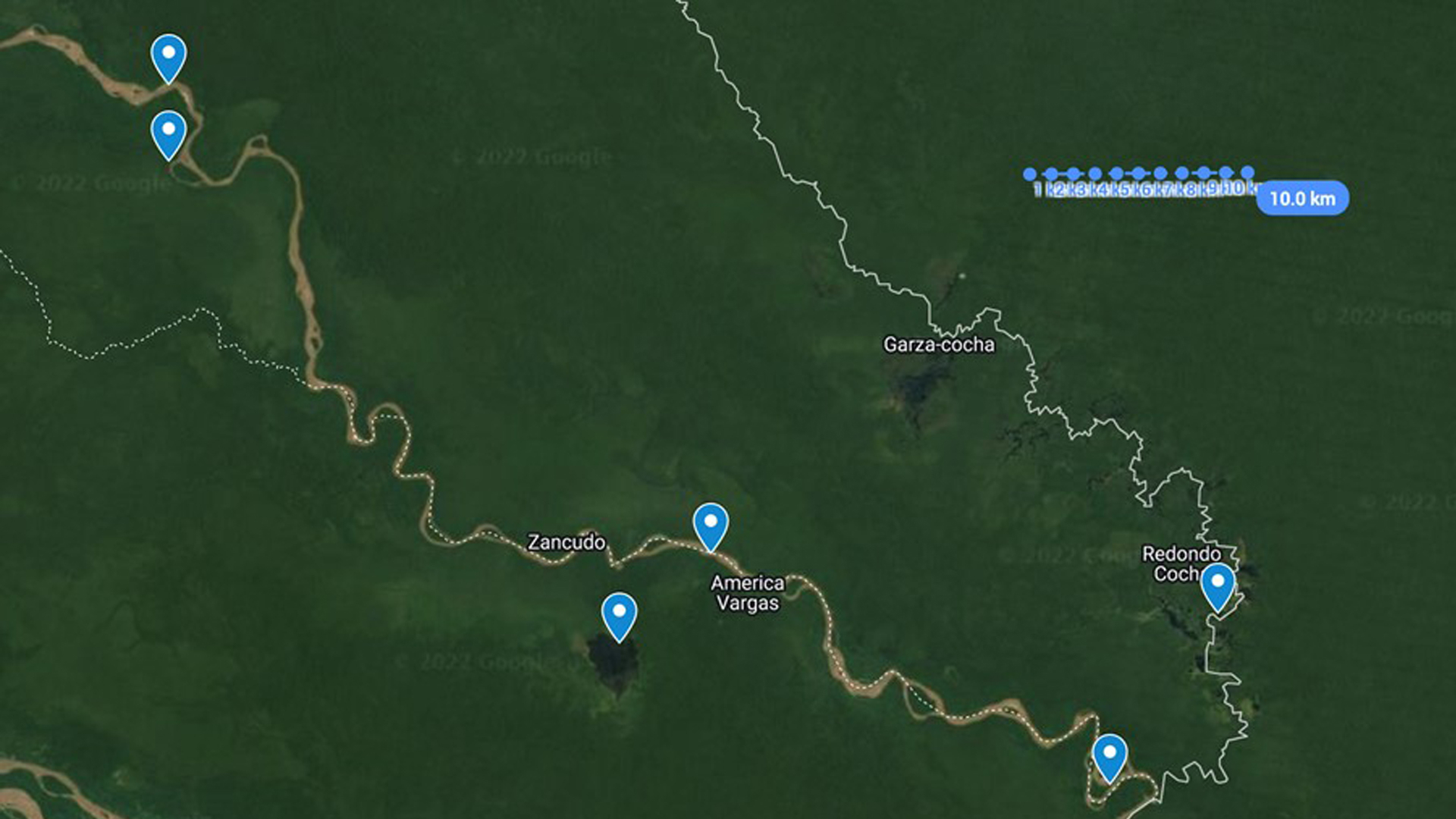

Left: A GoogleEarth satellite view of the team’s various field sites along the Pastaza River. Centre: Sitting on buckets and boxes, Lujan and colleagues process an array of fresh specimens. Photo by Ruben Shakay. Right: Daniel Zambrano from the Universidad de las Americas extracts a tissue sample from a freshly caught Auchenipterus specimen. Photo by Nathan Lujan.

Mud and mayhem on the Pastaza River

March 25–30, 2022

One of the first stops of the trip was the Pastaza River, where there are no Arapaima, but many other little-known fish species. And while the fishing was ideal, the living conditions were anything but.

“It was just a world of mud,” said Lujan. “And we didn’t have a particularly good water supply.” Still, the team persisted, turning their muddy campsite into a makeshift laboratory and operating room, where they took tissue samples, DNA samples, soil samples, water samples, and more. As part of their research, which is administered by the UDLA and funded by UDLA and World Wildlife Fund-Ecuador, the team mapped the distribution of heavy metals and mercury in the environment, tracking how they move up the food chain.

“Heavy metals and mercury are fat soluble,” Lujan explained. “As a result, they bioaccumulate, so when you eat them, you’re taking in the fat of the prey item, assimilating it into your own, causing it to concentrate up the food chain in top predators, ultimately threatening them and the people who depend on these fishes as a food source.” Resolving the distributions of heavy metals and mercury in the environment and food chain was primarily the responsibility of Montoya, who is an expert in the sediment ecology of Neotropical rivers.

The crew also set up gillnets (big walls of netting) in remote lagoons and main channels of the lower Bobonaza River. These nets are great for catching fish, but if left unchecked, those fish become easy prey for piranhas and black caiman crocodiles. So, the nets must be inspected every few hours—including at night.

All that nonstop work, combined with disruptions to the team’s plan for clean water, left several sick with dysentery. Lujan, who got it the worst, lay curled at the bottom of the boat during the rain-soaked eight-hour trip to their final site. Feeling sick and exhausted, all he could do was try to ‘hold on’ and hope the antibiotics he took worked quickly.

The first Arapaima

April 2–15, 2022

After a few days of rest and sun, Lujan was back to himself—and back to work in the Napo and Aguarico river drainages in northern Ecuador. For two weeks, Lujan, Montoya, and their crew travelled and sampled these headwaters of the Amazon, eventually making their way to the Zancudo Cocha lagoon near the border of Peru, which has a healthy, well-protected population of Arapaima.

Accompanying the team was Francis Boily, a Canadian sport fishing and ecotourism guide living in Ecuador. And in Zancudo Cocha, they met up with Enrique Moya, president of the nearby Kichwa indigenous community and another avid sports fisherman. Boily and Moya are partners in the new, nearby Tukunari ecotourism lodge and, together, they are an unstoppable fishing team.

By 11:00 am on the first day, they caught the first and largest Arapaima of the trip: an incredible two metre, 200-pound female.*

The whole team was ecstatic. It was a big, beautiful specimen that fulfilled a major goal of the expedition. But the fish was also heavy and hard to handle. If not properly preserved, it would soon begin to rot, so they took the giant fish back to camp, where they measured it and checked it for external parasites. It was covered in a few dozen Argulus—a common group of fish parasites, known colloquially as "fish lice"—which Lujan and Jonathan Valdaviezo, a fish biologist from Ecuador’s National Biodiversity Institute (INABIO), preserved for further study.

Then Lujan and Valdaviezo took their various tissue samples (DNA, stable isotopes, heavy metals, etc.). But the Arapaima itself was so heavy it was almost impossible to handle. Lujan figured the fish might be full of eggs, so to open the belly to preservative, reduce weight, and separately preserve the organs, they eviscerated it. Surprisingly, though, the fish’s ovaries were still small and immature, and the weight was simply due to its thick layer of body fat, which the team sampled for heavy metals.

Next came the embalming bath. The team dug a trench large enough to accommodate both the large Arapaima specimen in hand and any additional specimens that might still be harvested. They then lined it with plastic and filled it with a mix of river water and formaldehyde.

“This embalming chemical acts like a molecular stapler,” explained Lujan. “So, you have proteins, which are like balls of yarn, and those break down when flesh putrefies. But the formaldehyde staples each string to the others, stabilizing them and preventing them from rotting.”

The last Arapaima

April 13–15, 2022

After a day-long trip downriver, Lujan’s crew arrived at the World Wildlife Foundation-funded ranger station in Lagarto Cocha, which is perched on the border of Peru. Although far from luxurious, the camp had elevated floors, running water, and functioning washrooms. Plus, it was staffed by Kichwa from the Zancudo Cocha community, who were familiar with the biodiverse-rich area.

Two of the Kichwa, Tedi (Wilson Tedith Guaman Tangoy) and Byron (Byron Wilber Condo Avilés), were true paicheros—fishermen skilled at finding and catching Arapaima. So, Nathan asked them for their help.

The paicheros agreed, venturing off to a narrow passage where Arapaima cross from one lagoon to another. Next, they set up lines hanging from tree limbs on either side of the bank, using cichlid fishes as bait.

Back at the camp, Lujan, exhausted after weeks of travel and long days, worked with Valdaviezo and other team members to process smaller specimens collected that day, then everyone at camp finally crashed around 1:00 am.

Shortly after, around 2:30 am, a holler pierced the quiet darkness of the camp: “FISH!”

Groggy and bleary-eyed, Lujan dragged himself from his tent to the dock. “There were Tedi, Byron, and Francis, standing over two more big Arapaima,” he said.*

One had its tail mangled by a black caiman crocodile, while the other was pristine. But Lujan was too tired and disoriented to share in the excitement. Half his colleagues were still asleep, while Montoya and the ecologists were just waking for a 3:00 am sample of water chemistry and plankton. To make the most of these specimens, they needed to be processed quickly.

Knowing that it would be hard to transport three full-sized Arapaima, Lujan decided to skeletonize the caiman-mangled one, and, with no onsite embalming bath, the team needed to somehow pump the other specimen full of formaldehyde, then transport it back to their previous embalming pool, six hours away.

Under light rain and the glow of headlamps and flashlights, Lujan worked with the paicheros and Francis to skin and fillet the mangled Arapaima—gory, grueling, and time-consuming labour for a fish of this size. Then, the team turned to the other specimen.

“This time, instead of eviscerating it, we made a small incision in the abdomen and pumped straight formaldehyde into the belly,” Lujan said. Ecuadorian fish biologist Valdaviezo, who knew how to sew a wound, then sutured the fish shut.

As the sky pinkened and the camp began to rouse on the morning of their last day in Lagarto Cocha, Lujan felt a tug of relief. They had found and preserved three large Arapaima specimens, two of which would soon be the only whole large Ecuadorian specimens of this species in the world.

With them, scientists could help inform conservation efforts with new knowledge about the Arapaima’s genetic diversity, population structure, and regional uniqueness. There’s even the distinct possibility that one of the Arapaima populations in Ecuador might be recognized as a new species!

*Despite their size and strength, Arapaima are often quite fragile and intolerant of handling or long fights on hook and line. All three specimens harvested in this research died shortly after capture and before being processed and preserved. Collection and transportation of Arapaima specimens within Ecuador was made possible by Genetic Resource Access Permit MAAE-DBI-CM-2021-0152 and collection permit MAAE-ARSEC-2021-1630 issued to Ecuador’s National Biodiversity Institute (INABIO) and administered by INABIO Curator of Fishes Jonathan Valdaviezo. International transit of Arapaima specimen is only possible via institutional CITES authorizations granted to INABIO and ROM.