Unfrozen in Time: From the Erebus and Terror to the ROM

Guest Blog by Dorea Reeser, Ph.D., Environmental Visual Communication Student, ROM Biodiversity and Fleming College

Special thanks to Tim Dickinson, ROM Senior Curator of Botany, Emeritus

Ahoy there! For 167 YEARS, the search for Sir John Franklin, his crew, and their lost ships, the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, has captivated and mystified many. Throughout this search, most of the attention has focused on the mystery; what happened to Franklin? Where are the bodies? Where are the ships? So when the Erebus was FINALLY discovered and identified by a team from Parks Canada in early October, 2014 the excitement was overwhelming. The story is a rich one, with many exciting discoveries yet to be found. However, consider how many other major contributions this long investigation has made to different fields of study, including archaeology, the social sciences, as well as botany.

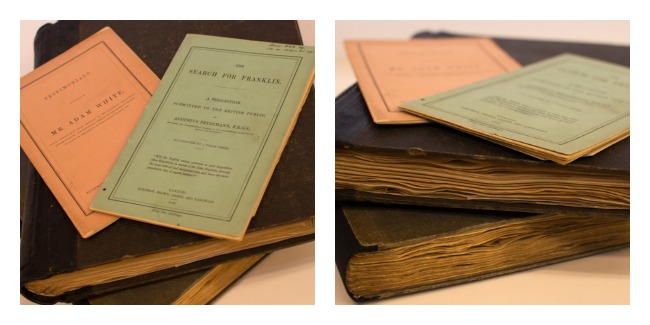

Today’s blog post is a glimpse of a tale that is largely untold. It is the story of the exploration of the Canadian Arctic, as seen by Adam White in his botanical scrapbooks. These scrapbooks were donated to the University of Toronto by one of Adam White’s descendants who settled here, and came to the ROM together with what is now the ROM’s Green Plant Herbarium. What do these scrapbooks have to do with Franklin, the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror? It’s a fantastic story!

First, who was Adam White and what’s so special about these scrapbooks? Adam White worked at the British Museum as an entomologist but had “an eye for flowers.” Because he couldn’t afford to travel far, he travelled vicariously through his friends. His friends just happened to be world-renowned explorers and naturalists, like Sir John Richardson and Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker. These guys would give Adam White samples for his scrapbooks whenever they returned from expeditions.

After the Napoleonic wars ended (c. 1815), England had more ships and men in her navy than were needed for defense. Many men were pensioned off, but many others volunteered to take part in scientific expeditions all around the globe. One objective of these expeditions was to find the Northwest Passage from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. William Parry, shown in the engraving below that was pasted into Adam White’s Arctic scrapbook, came close to discovering the Northwest Passage in 1820. Plants collected on Parry’s expedition were sent to Robert Brown (ever hear of Brownian motion?) at the British Museum.

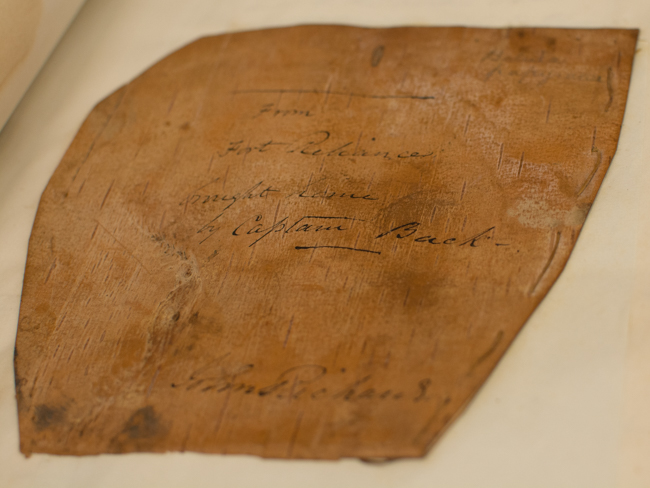

Other expeditions to explore Arctic Canada went overland, and two of these were led by none other than Sir John Franklin, accompanied by Sir John Richardson and George Back. George Back led an expedition 1833-1835 on which one of his specimens, a bat, was sent home from Fort Reliance on Great Slave Lake packed between sheets of birch bark, one of which Richardson gave to Adam White.

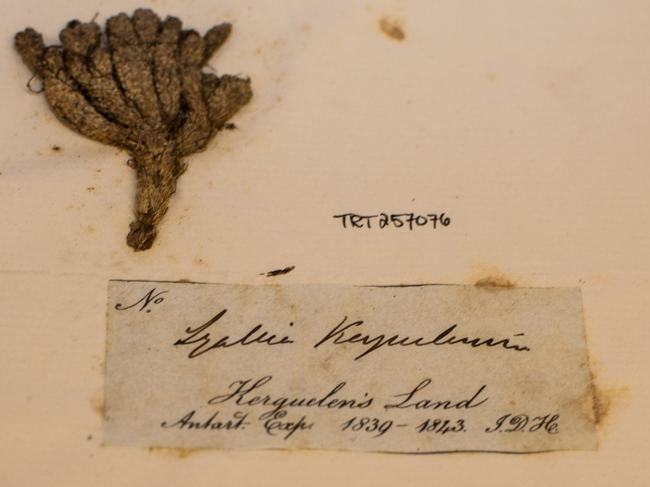

Two of the Royal Navy ships that were outfitted for polar exploration were the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. In 1839 they were dispatched under Sir James Clark Ross to circumnavigate Antarctica. On board each ship was an assistant surgeon who would double as a naturalist. These posts were filled by two 22 year old botanists, J. D. Hooker on HMS Erebus, and David Lyall on HMS Terror. Lyall was to remain in the navy all his life, and botanized all around the world. Hooker sought to emulate Charles Darwin’s voyage on the HMS Beagle and go on to a career in science. He eventually succeeded his father as the Director of the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew.

Hooker gave many of his duplicate specimens to Adam White, among them this specimen of Lyallia kerguelensis, a species that Hooker discovered on the island of Kerguelen in the Indian Ocean and named after his friend Lyall. Because this specimen is part of the material Hooker used to describe the new species, it’s called a type specimen, and is of special importance for biological research. You can find much more about this and other specimens from the Antarctic expedition scrapbook here.

After their return from the southern hemisphere the Erebus and the Terror were fitted out for yet another expedition seeking the Northwest Passage, to be led once again by Sir John Franklin. The expedition departed England in 1845, and was not heard of again. In 1847 Sir John Richardson, now 60 years old, returned to Canada to seek news of the Franklin expedition. He traveled overland, and searched along the coast of the Arctic Ocean from the mouth of the MacKenzie River to that of the Coppermine. Adam White’s Arctic scrapbook contains 13 plant specimens that Richardson collected and gave to Adam White after his return in 1850.

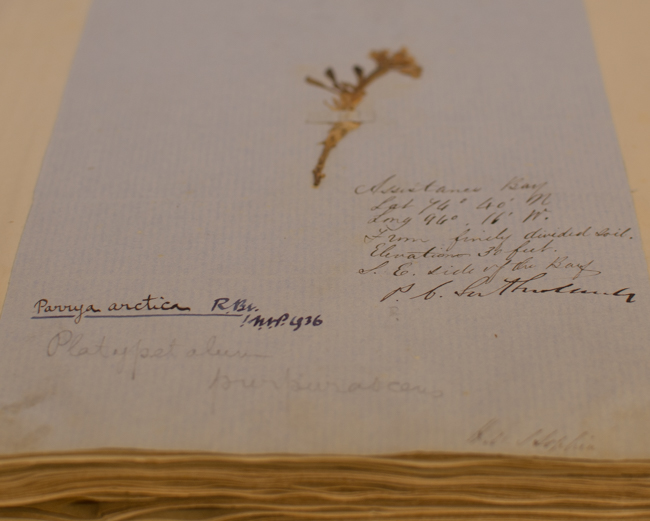

This scrapbook features many more specimens that were given to Adam White by two others who helped search for the Franklin expedition, Peter Cormack Sutherland and Charles Ede. You can find more information about this scrapbook here. As you can see, this scrapbook contains not only botanical specimens, but also beautiful watercolors - and it tells us about an important part of Canadian history.

Robert Brown named Parrya arctica after the Arctic explorer William Parry (remember him?). Adam White was proud to include in his Arctic scrapbook four specimens of Parrya arctica, including one given him by Robert Brown himself, that Brown inscribed as having been collected on the expedition, also in search of the Franklin expedition, that was led by James Clark Ross, 1848-1849.

As we know, none of these 19th century expeditions ever discovered the fate of the Franklin expedition ships, the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. Augustus Petermann, a fellow of the Royal Geographic Society, published “Predictable positions of Franklin’s Expedition” in 1852. We now know that the ships never made it as far west and north as Petermann imagined. Instead, the HMS Erebus has been found off King William Island, more than 600 km further east than Richardson had searched.

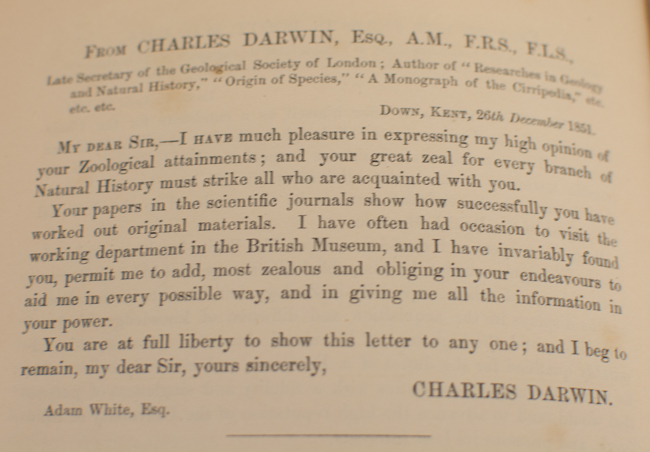

And what became of Adam White? He applied for a teaching position in his native Scotland, and solicited testimonials from many of the scientists whom he knew from the British Museum, including Charles Darwin. He withdrew his application when he learned that a much more successful naturalist had also applied for the same position. Nevertheless, he returned to Scotland, where he advocated for the creation of a Scottish national museum that would be freely accessible to all. Online you can find a touching anecdote about Darwin and Adam White that shows how much White was troubled by the implications of Darwin’s theory of evolution.

The story of Sir John Franklin and his crew, the discovery of the HMS Erebus and the continuing search for HMS Terror is fascinating stuff. Parks Canada and their partners are at the forefront of this and are doing an excellent job inspiring Canadians, and the world, about the history of our lands and waters.