To X-Ray an Egg: Behind the Scenes of Empty Skies

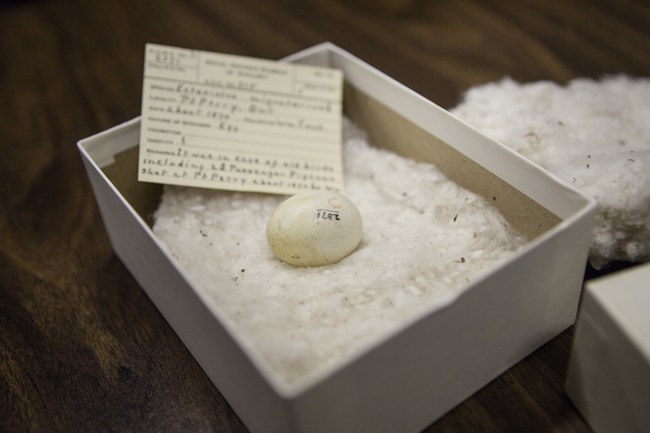

“That egg is approximately one hundred and forty-four years old,” says Brad Millen, a technician who works in the ROM’s Natural History collections. Suddenly the large speckled shell that sits in the palm of my hand feels just a little bit heavier. I feel the weight of its place in the world - it is the egg of a passenger pigeon, and its species has been extinct for a hundred years. Brad plucks it gently from my hand, holds it between finger and thumb, and shakes it. Something rattles loudly inside, and everyone in earshot perks up.

The egg’s ROM collections tag tells of its origins - donated to the museum along with a couple of adult male passenger pigeons that were shot and killed in Port Perry, Ontario circa 1870. It was around that time that the massive and unstoppable decline in the species’ population began. It was also only a couple of decades before Martha, the last passenger pigeon, was born. This little egg has some gravitas, and today we are going to see what secrets it holds.

The ROM was the first cultural institution in Canada to go digital with its x-ray department. As we all pile into the x-ray room, the senior conservator of paintings, Heidi Sobol, tells us that what we’re doing today would’ve taken hours on a traditional x-ray machine, whereas our digital x-ray view into the egg will take mere minutes. In her work with paintings, Heidi uses the machine to look deeper into works of art, and discover things about them that might be hidden to our eyes - like other paintings underneath the topmost layer, or different creative decisions the artist decided to abandon and paint over. Today, she is helping us look beneath the egg’s shell to figure out what exactly is rattling around inside of it.

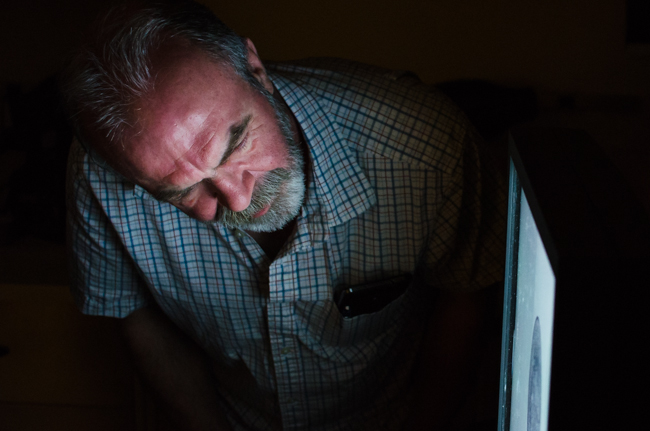

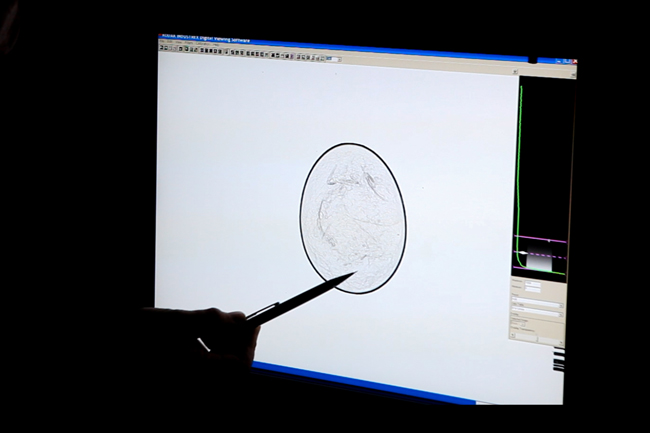

Once the first scan is completed, the lights in the room are dimmed. Everyone waits for the x-ray image to appear on a computer screen, their faces lit by the blue glow of the monitor. When the first white oval image appears, we all crowd in closer, searching for signs that something pigeon-shaped might have been starting to grow inside, before the egg was collected. Photos are snapped, tweets sent out to the interwebs, and Brad tells us the news: there’s no little mummified pigeon embryo inside - just dried egg contents rolling around in there. Brad tells us he can use the x-ray images to help him drill a hole in the egg, to take samples of the material inside. “It’s rather cool that we found this and can share it with everyone,” he says, “because once I get the contents of this egg removed, I can save it for DNA and we can do barcoding of the specimen. This is so great for a Friday afternoon!”

For more information about passenger pigeons and their extinction, visit the new exhibit Empty Skies: The Passenger Pigeon Legacy. If you're interested in a conversation about the possibilities of their de-extinction, check out our exclusive event on September 26th, De-Extinction Dialogues with Dr. Joel Greenberg (@joelgreenberg) from the Chicago Field Museum, and Dr. Ben Novak of Revive and Restore.