Love and Fungi

Published

Category

N/A

Forget swooning songbirds. Ditto for red roses and pink-cheeked cherubs slinging arrows. This Valentine’s Day, I wanted to showcase something unexpected, something weird, something fungal.

I reached out to my frequent collaborator Simona Margaritescu, a collections specialist and mycology expert, asking her to surprise me with some specimens in the spirit of season. Her selections, which run the gamut from folkloric wonder to fungal horror, are a reminder that love takes many forms – some gross, some gorgeous, all fascinating.

Cœur de sorcière (Clathrusr ruber)

Latticed stinkhorn (Clathrusr ruber)

The latticed stinkhorn begins “like a little white egg” on the forest floor, feeding on dead plant material. “This whole complex, lattice-like structure, which represents the fruiting body of the fungus, is right inside,” says Margaritescu. “And when the fungus is ready to bloom, it pops up like a jack-in-the-box.”

For her, the ruby-red fungus is akin to a little basket of interesting gifts, much like a Valentine’s Day present. But, true to its name, the lattice stinkhorn stinks—and of rotting flesh, no less. However, as Margaritescu reminds me, “not everyone likes the same thing.” And while the stinkhorn’s smell might repel people, it’s “actually extremely yummy and loveable for insects,” who, enticed by the smell, later spread the stinkhorn’s spores.

If that’s not true love, what is?

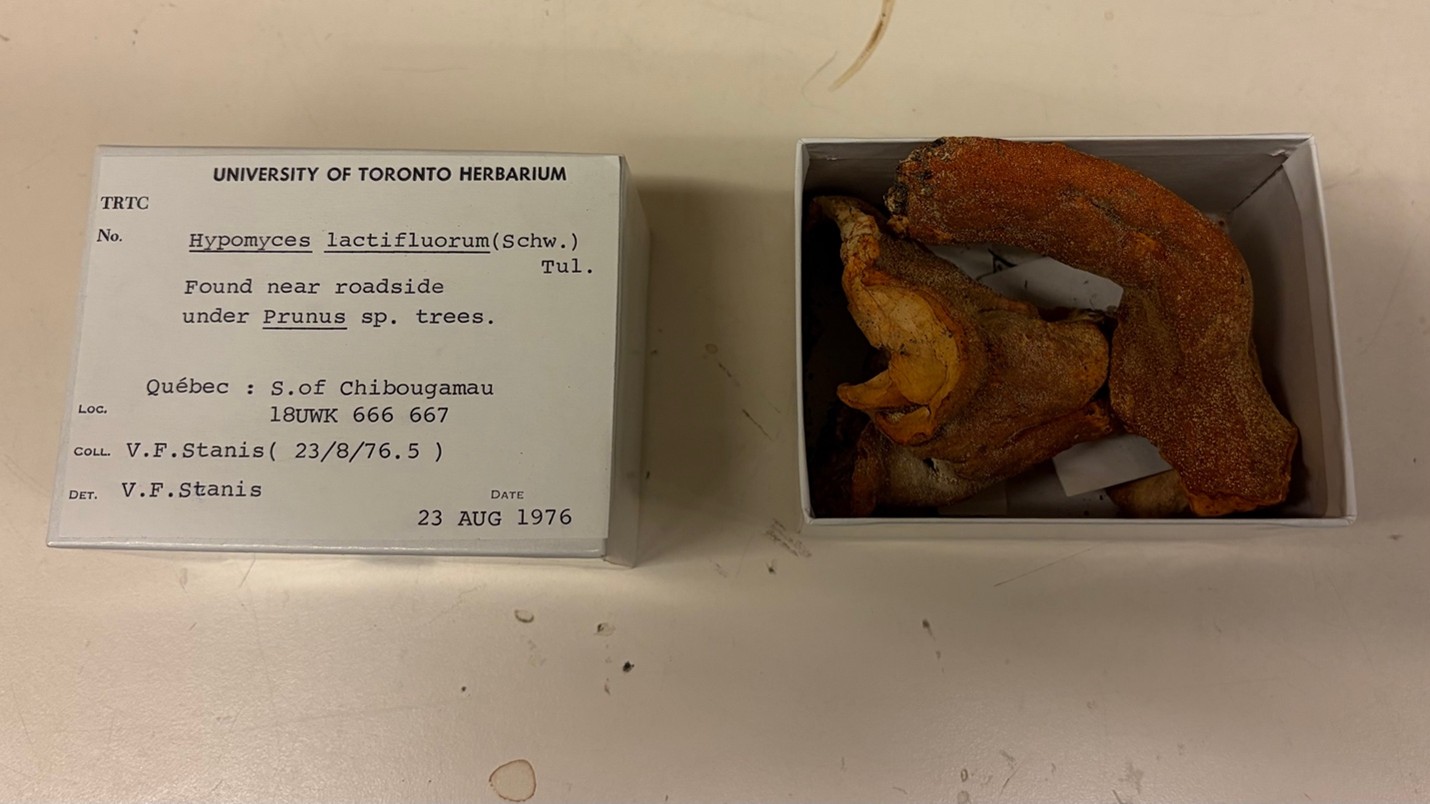

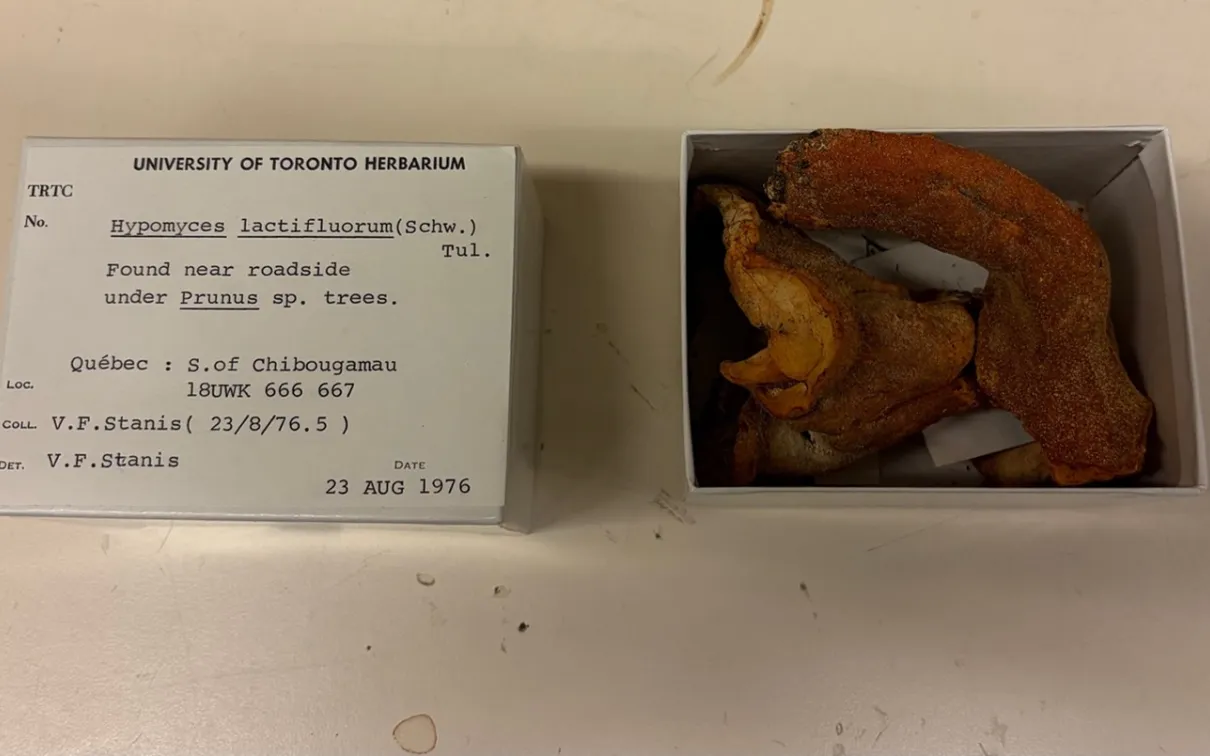

Champignon homard (Hypomyces lactifluorum)

Lobster mushroom (Hypomyces lactifluorum)

Unlike stinkhorns, lobster mushrooms—named after their fishy flavour and the colouring of a boiled lobster—do make for a nice Valentine’s Day meal, especially when fried in butter. But the romance doesn’t stop there.

“This fungus is actually two fungi in one,” Margaritescu says. More precisely, Hypomyces lactifluorum is a microfungus that parasitizes a bigger mushroom like Russula or Lactarius. “That beautiful red you see on the outside is the parasite taking over and slowly consuming the mushroom.”

The microfungus’s all-consuming love doesn’t just change the appearance of the organism—it alters its very DNA. In fact, as Margaritescu explains, scientific studies found that when “trying to look at the DNA makeup of this union, most of the time what you find is the DNA of the parasite.”

N/A

Scarlet elf cup (Sarcoscypha coccinea)

Margaritescu’s third and final pick is pure fairy-tale whimsy, without so much as a whiff of death or parasitism. In fact, scarlet elf cups are so named because, according to European folklore, they’re where fairies bathe and elves drink.

But she picked this species, which grows on trees, mostly because they’re one of the few fungi that produce fruiting bodies in the late winter and early spring. Margaritescu invites us to imagine spotting brilliant-red elf cups on a low-hanging tree branch against a backdrop of untouched white snow.

That’s more beautiful than a bouquet of roses.