From ROM volunteer to Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Publié

Catégorie

First

When Beckett Robertson’s email about volunteering came through in 2022, Antonia Guidotti, a seasoned ROM entomology technician, had every reason to say no. First, there was no official volunteer position available. Second, he was 14 years old—an age when maturity is scarce and passions are fleeting.

However, the note had been passed along by Dr. Christopher Darling, then Senior Curator Emeritus of Insects and Arachnids, to her and fellow technician Brad Hubley. Plus, Beckett Robertson was no ordinary teenager.

Instead of comics, he read 700-page insect field guides. Instead of dogs or cats, his pets were arachnids—specifically giant whip spiders, which “appear to have been formed in the deep recesses of a human nightmare,” according to Orin McMonigle, who literally wrote the book on them: Breeding the World's Largest Living Arachnid. But, perhaps most impressive at all, Robertson was willing to do whatever was needed for the collections.

“He was really, really keen,” says Guidotti.

So, she and Hubley created a position for the 14-year-old. And that summer, Robertson joined them at ROM, where he was put to work checking the collections for pests.

It’s the kind of mundane activity that even Guidotti admits is one of the less interesting parts of the job, but Robertson was thrilled to be at ROM—and happy to put in the work.

“We were really impressed with him,” she says.

Second

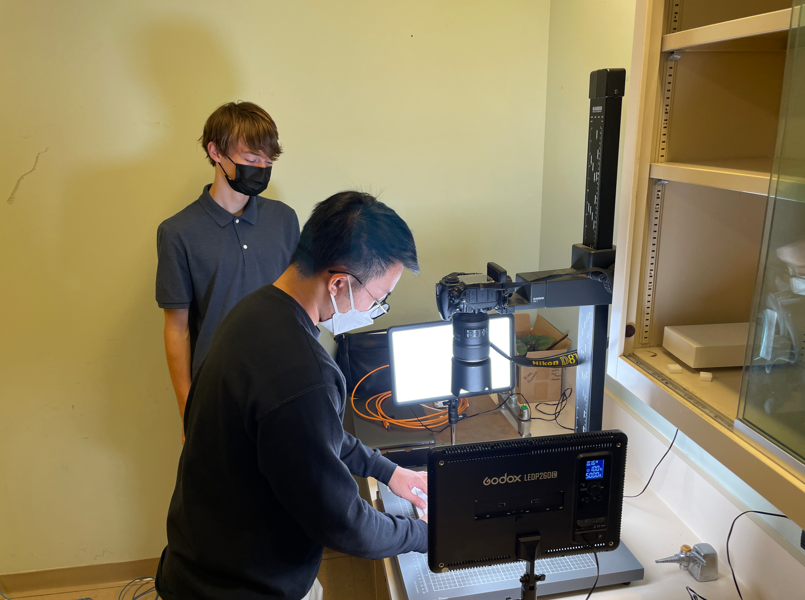

The next year, Guidotti and Hubley tapped into a provincial program for funding so they could recruit summer students for collections imaging. Unsurprisingly, Robertson was the top candidate. And by summer 2023, he was back at ROM—this time photographing moths, cicadas, and beetles.

It’s delicate, painstaking work that cannot be rushed. Each specimen must be handled with care, each data point entered into Excel with exactitude.

“It’s important to take the time you need to do the photos because it can get repetitive,” explains Robertson. “But it was kind of a dream job for me.”

Third

As Guidotti and Hubley soon learned, not only was Robertson meticulous, he was talented—especially at photography. He had already won First Place in the Junior Category for the ROM Wildlife Photographer of the Year Contest in 2022 for a stunning photo of a jumping spider. And when Robertson showed some of his other photos to Hubley, Hubley encouraged him to compete in the global version of the competition.

“We were confident he had the skills and the eye to do well on the international stage,” says Guidotti.

She was right.

Into the spider cave

Forget beautiful beaches. On a family vacation to the Dominican Republic, Robertson was drawn to the caves.

These caves are, as he learned from his extensive reading, home to some of the world’s largest whip spiders, so named because their “front pair of legs have evolved into long, whip-like limbs they can use as sensors.”

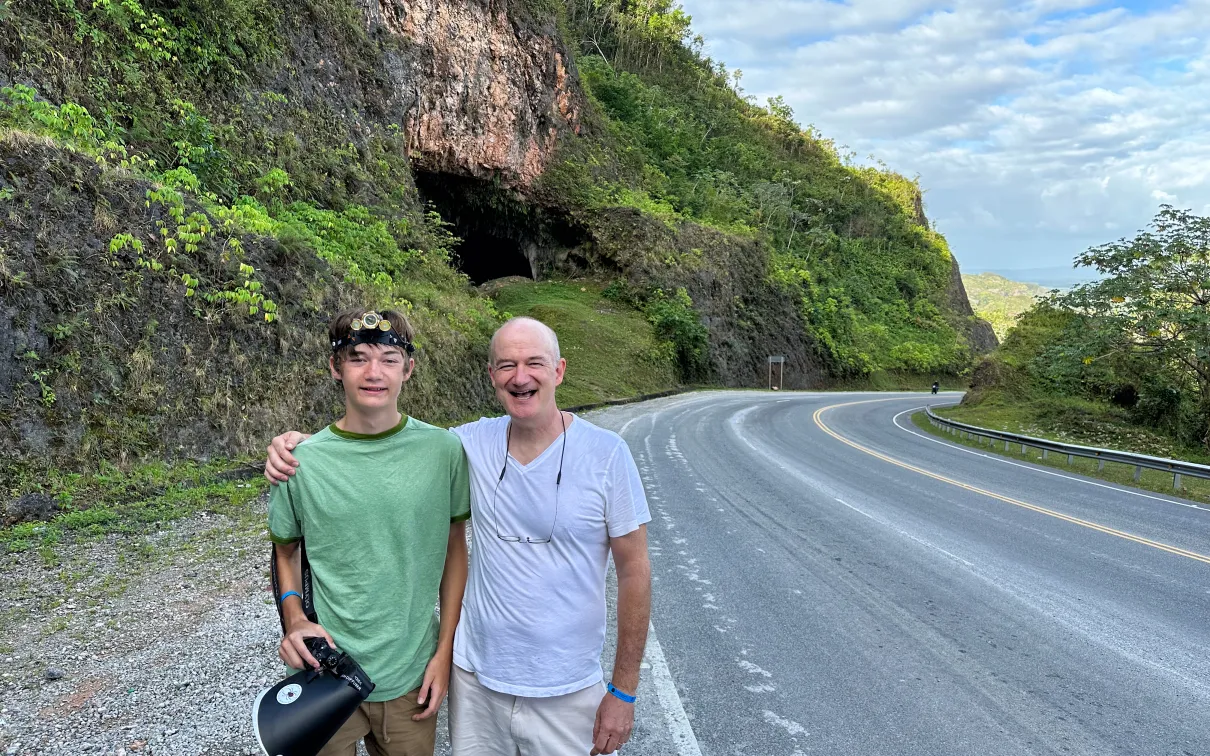

But at age 15, Robertson was unable to drive himself around the Dominican Republic. So, he did what many teenagers do—he got a ride with his dad.

fourth

Together, the pair drove along a scenic highway, parked, and hiked to their final destination: Cueva Boulevard del Atlántico, a cave full of stalactites, stalagmites, and spiders. As his dad hung back near the mouth of the cave, taking photos of his own, Robertson, with his camera gear in tow, ventured deeper inside.

It was dark, the cave floor slippery with guano. So, Robertson trod carefully, lest he fall or kick up dust potentially laced with disease. There was also the issue of recluse spiders—whose bites can sometimes cause dermonecrotic lesions—crawling along the rocks and walls. Robertson, however, was unconcerned.

He’d been bitten by ants and stung by a scorpion before. Plus, recluse spiders aren’t aggressive and unlikely to bite unless provoked, he says.

Robertson kept moving, kept climbing. Then, on the ceiling at the back of the cave, he finally found what he was hunting for: a massive whip spider, as alien and nightmarish as almost any creature of Earth. Robertson steadied himself, raised his camera, and started shooting.

Fifth

The best of the bunch—a terrifying closeup of the momentarily still creature—is now on display at ROM in Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2025, the most prestigious competition of its kind in the world.

The next chapter

Robertson, now 18, is currently living in Costa Rica. He’s enrolled in a Spanish course and, by his own admission, “starting from a very beginner level.” In his downtime, he’s photographing bark scorpions around the city—an activity that worries his mom to no end.

“She calls me every 10 or 15 minutes to see that I’m still doing well,” he says.

Once the course wraps up, Robertson is off to the Osa Peninsula—“a wild and remote corner of Costa Rica, which happens to be home to one of the most biodiverse places on the planet” to volunteer with the local non-profit Osa Conservation, which, in addition to planting trees and releasing sea turtle hatchlings, is focused on “rebuilding habitat connectivity.”

For Robertson, it’s a chance to combine his love of conservation and fieldwork. After his year in Costa Rica is over, he’s planning to study zoology at the University of Guelph.

“I’m really thrilled for Beckett,” says Guidotti. “It always pleases me when one of the students we were able to hire goes on to do things that they're passionate about. Of course, if it's entomology, we're even more pleased about it.”

While he hasn’t even begun his classes, Robertson is already toying with the idea of a master’s and a PhD in entomology. He might even return to ROM one day—perhaps this time as a technician or a curator.

Book your ticket to Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2025—on now at ROM.

Sixth

Colin Fleming is the Executive Writer & Creative Communications Strategist at ROM