Drawing the Holocaust

Publié

Catégorie

Few Survived Auschwitz. Even fewer survived, then escaped only to be recaptured—and survive again. Jan Komski was one of them.

Few survived Auschwitz. Even fewer survived, then escaped only to be recaptured—and survive again. Jan Komski was one of them.

Komski was born on February 3, 1915, to a Catholic family in the town of Bircza, Poland. His parents, he told the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1990, were “hard-working people” struggling like everyone else in their small town. As a young man, Komski moved to Kraków to study art and art history at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts. The large Polish city was, in the budding artist’s eyes, “a beautiful place to live in” with a multitude of landmarks, churches, and synagogues. But not long after Komski graduated in 1939, war broke out—and everything changed. “The Germans were everywhere,” he told the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Then of course, the persecutions started immediately.

By 1940, Komski was a member of the Polish underground, resisting the Nazi occupation. But he was soon arrested near the Slovak border while carrying forged identity papers. And on June 14, 1940, the very day the concentration camp opened, the young Polish painter under the alias Jon Baraś—arrived in Auschwitz as one of its first prisoners.

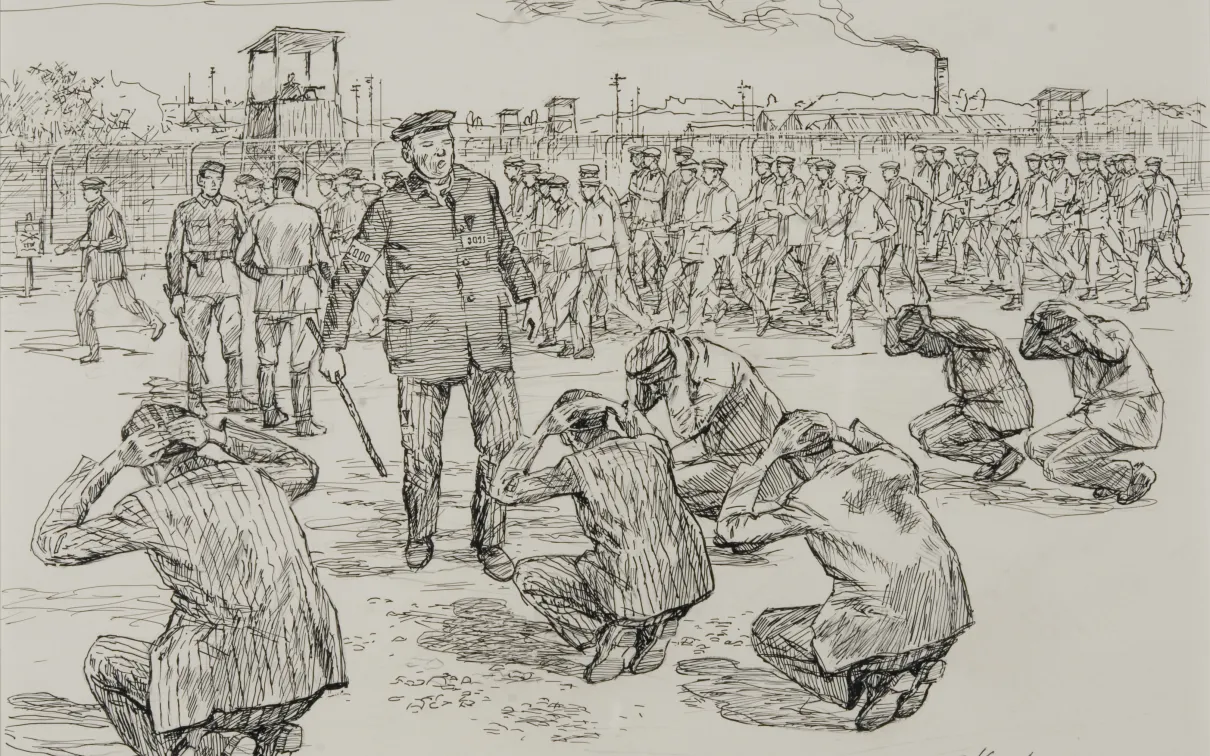

There, Komski drew designs for new buildings in the fast-expanding camp complex. And while his skills and non-Jewishness spared him from the gas chambers, Komski bore witness to the violent cruelties of daily life: hangings and beatings and masses of naked, emaciated bodies that would, many years later, materialize as detailed artworks.

On December 29, 1942, Komski and three friends, one of whom was disguised in an SS uniform, made their great escape. Although Komski was reportedly able to turn over intelligence to the underground, he was soon arrested on a train to Warsaw. Since he was originally arrested using the alias Jon Baraś, the Nazis never clocked him as an escapee—and his life was spared. But he was sent to Montelupich Prison, then back to Auschwitz.

“Then began a kaleidoscope life as Komski was herded from camp to camp: Birkenau, Buchenwald, Grosse Rosen, Hersbruck, Dachau,” the Washington Post reported in 1979. “The SS regarded him as a mystery man, for his credentials didn’t check out. He was tortured. He was cajoled into painting portraits of the guards. He became head cook at one place, serving 2,000 prisoners.”

Finally, on April 29, 1945, in Dachau, Komski was liberated by the U.S. Army. After marrying a fellow Auschwitz survivor, he moved to the U.S., where he joined the Washington Post as a graphic artist.

More than a decade later, on a trip to the Museo Nacional del Prado in Spain, Komski saw Francisco Goya’s series Disasters of War: a collection of 82 realistic prints, rife with carnage and terror. Inspired, Komski began to paint his memories from his life as a prisoner—memories that, decades later, would become an essential throughline in the exhibition Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away.

In Auschwitz, Komski bore witness to the violent cruelties of daily life that would, many years later, materialize as detailed paintings.

As the exhibition’s curators began selecting objects for what would become Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away., they knew they needed some kind of pictorial evidence of life inside the Auschwitz camp complex.

As the exhibition’s curators began selecting objects for what would become Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away., they knew they needed some kind of pictorial evidence of life inside the Auschwitz camp complex.

This led them to the Auschwitz Album, a collection of Nazi photographs Auschwitz survivor Lily Jacob found in an abandoned SS barracks on the day she was liberated. According to Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, the album contains, among its many startling images, “the only photographic evidence of Jews arriving in Auschwitz or any other death camp.”

Many of the album’s photographs appear in ROM’s exhibition. But for Luis Ferreiro, the Director and CEO of Musealia, who first conceived of the exhibition, the photographs from the Auschwitz Album, as well as others taken by Nazis, were insufficient. “There’s always the view of the person who takes the picture in a photo,” he says.

What they needed was a different perspective: images that emerged from the prisoners’ experiences, not “the lens of the perpetrators.” Something, Ferreiro adds, that would “balance the toxicity of the other pictures.”

Because no such photographs existed, Ferreiro, the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum, and the exhibition’s curators turned to art. But this too presented a problem. “Most of the survivors,” explains lead curator Dr. Robert Jan van Pelt, “made very expressionist images … that force you to come to a conclusion.”

What Ferreiro, van Pelt, and the other curators were looking for was something more journalistic. That brought them to Jan Komski. “He’s very precise, almost as if he’s reporting as an outsider,” says van Pelt.

What Ferreiro, van Pelt, and the other curators were looking for was something more journalistic. That brought them to Jan Komski. “He’s very precise, almost as if he’s reporting as an outsider,” says van Pelt.

Komski depicts a whole range of situations inside the Auschwitz camp complex, from the mundane to the murderous. “When he shows the hanging of a person or the beating of a person, he doesn’t change his visual language,” says van Pelt. “It’s exactly the same.”

This consistency, van Pelt continues, is like a bassline in a piece of music, gently guiding the listener. And in the case of Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away., that consistency is also a reminder that these images are not some artist’s fantasies or interpretations. They’re the memories of Jan Komski.

Colin J. Fleming is Senior Communications Creative Strategist at ROM

Colin J. Fleming is Senior Communications Creative Strategist at ROM.