The Reductionist

ROM photographer Paul Eekhoff on shooting Mobile Palace and his beetles side hustle.

Published

Category

After a series of stops and starts

After a series of stops and starts during the pandemic, Paul Eekhoff is now finally settling into his role as a photographer for the Museum.

While most artists insert themselves into their work, he sees himself as a “reductionist”—stripping away everything extraneous from dust and debris to noisy backgrounds, so objects are captured at their purest. Over an hour in March, we talked about everything from his artistic philosophy to his side hustle photographing beetles.

This is Paul Eekhoff.

On Shooting Mobile Palace

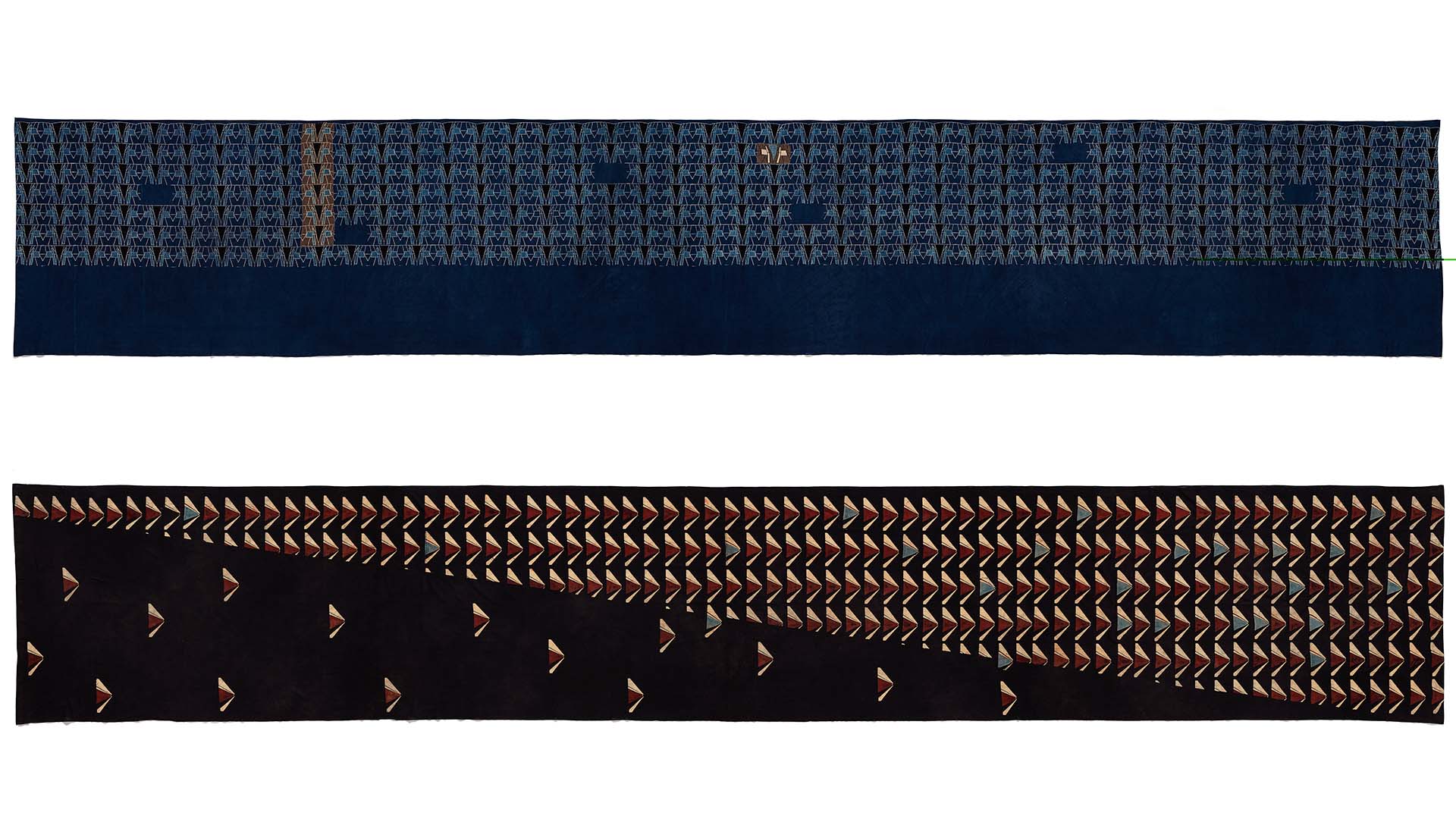

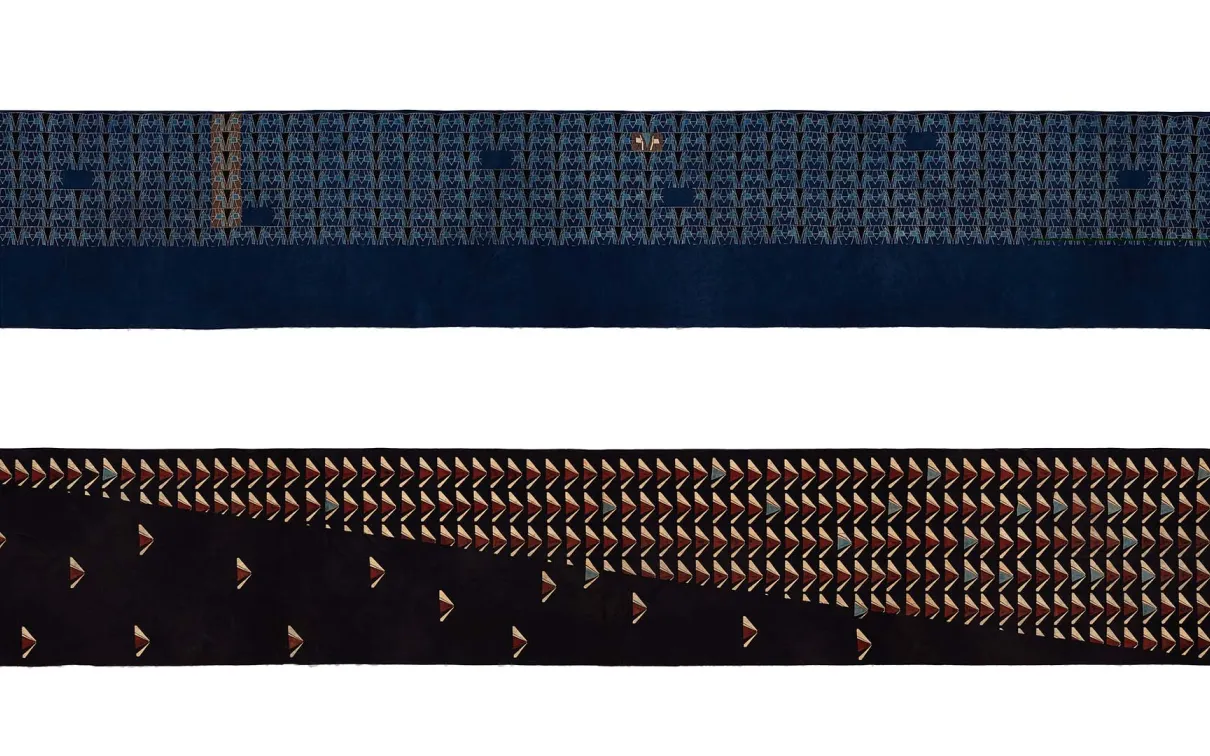

In a Museum with hyper-delicate fossils and giant works of art, there is no shortage of tricky technical problems when it comes to photography. Case in point: Swapnaa Tamhane: Mobile Palace, an exhibition of large, ornately patterned swaths of fabric that ripple like waves and form majestic tents. For two entire days, Eekhoff photographed the details using focus stacking—a technique he’s employed for 12 years.

“Think of it like a stack of paper,” Eekhoff explains. “When I’m photographing an object at an angle, I have one part of the object that is close to me and one that’s further away. My focus stacking creates a series of photographs with the camera lens focused on different points. Then we use software to stack photographs together, and it produces one final image in focus from front to back.”

After photographing the details

After photographing the details, Eekhoff shot Tamhane’s pieces from the ROM mezzanine with a camera mount suspended from the ceiling to capture them in their entirety.

“We rolled out the panels and sections, photographed each section, and then stitched them together with software.”

On Typology

One of the cornerstones of Eekhoff’s artistic philosophy is what he calls typology—a consistent aesthetic across a body of work that explores ideas of “similarity and difference, of familiarity and discord.” Like a brand’s visual identity, he wants each group of objects to have their own look and feel. Take the Willner Madge, Gallery of Life as an example. To give the millions-year-old fossils the heft they deserved, Eekhoff pushed for a solid black background for every object.

Gallery 1

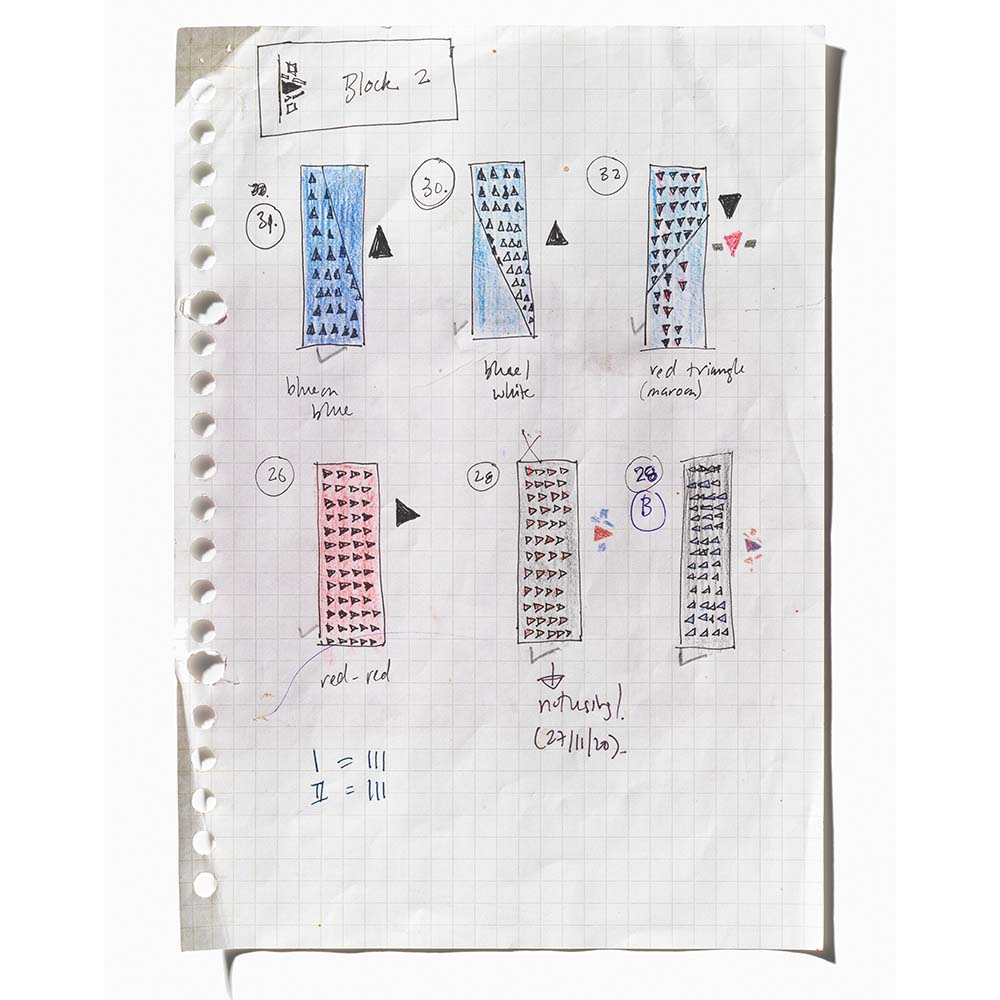

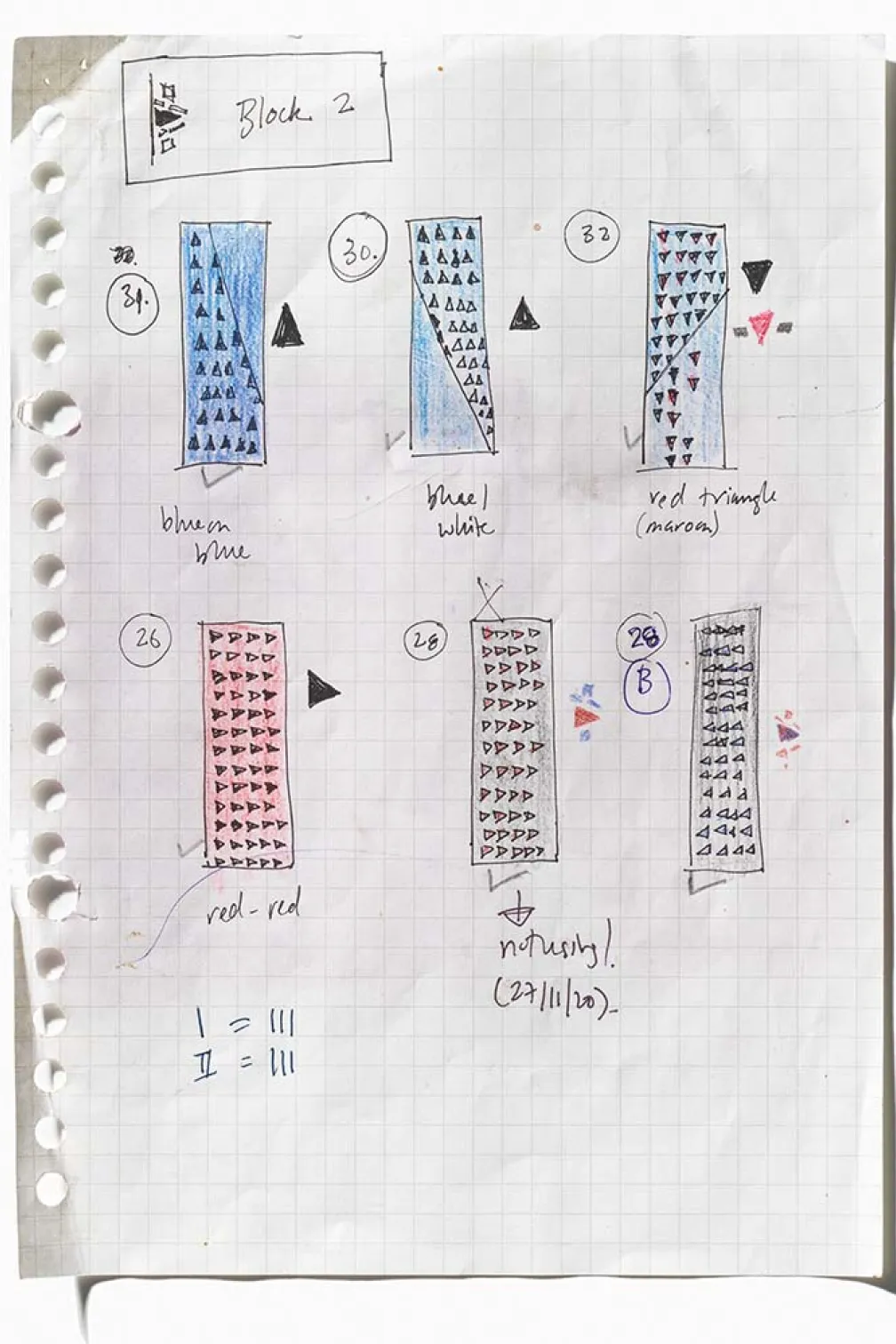

But with Mobile Palace

But with Mobile Palace, Dr. Deepali Dewan, the curator of the exhibition and the Dan Mishra Curator of South Asian Art & Culture, needed something different. So, Eekhoff used white backgrounds instead of black, and added shadow to pages from Tamhane’s sketchbook, which “set the foundation for how some of the other work would look.”

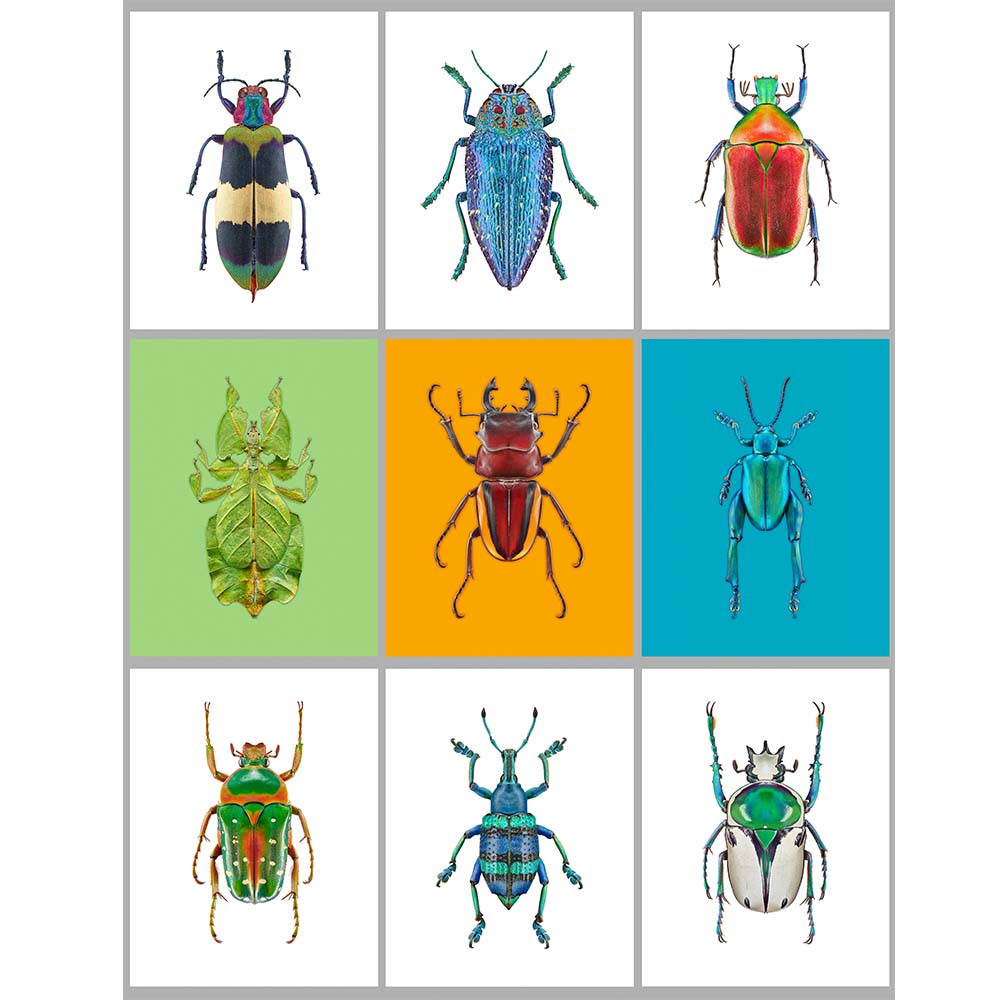

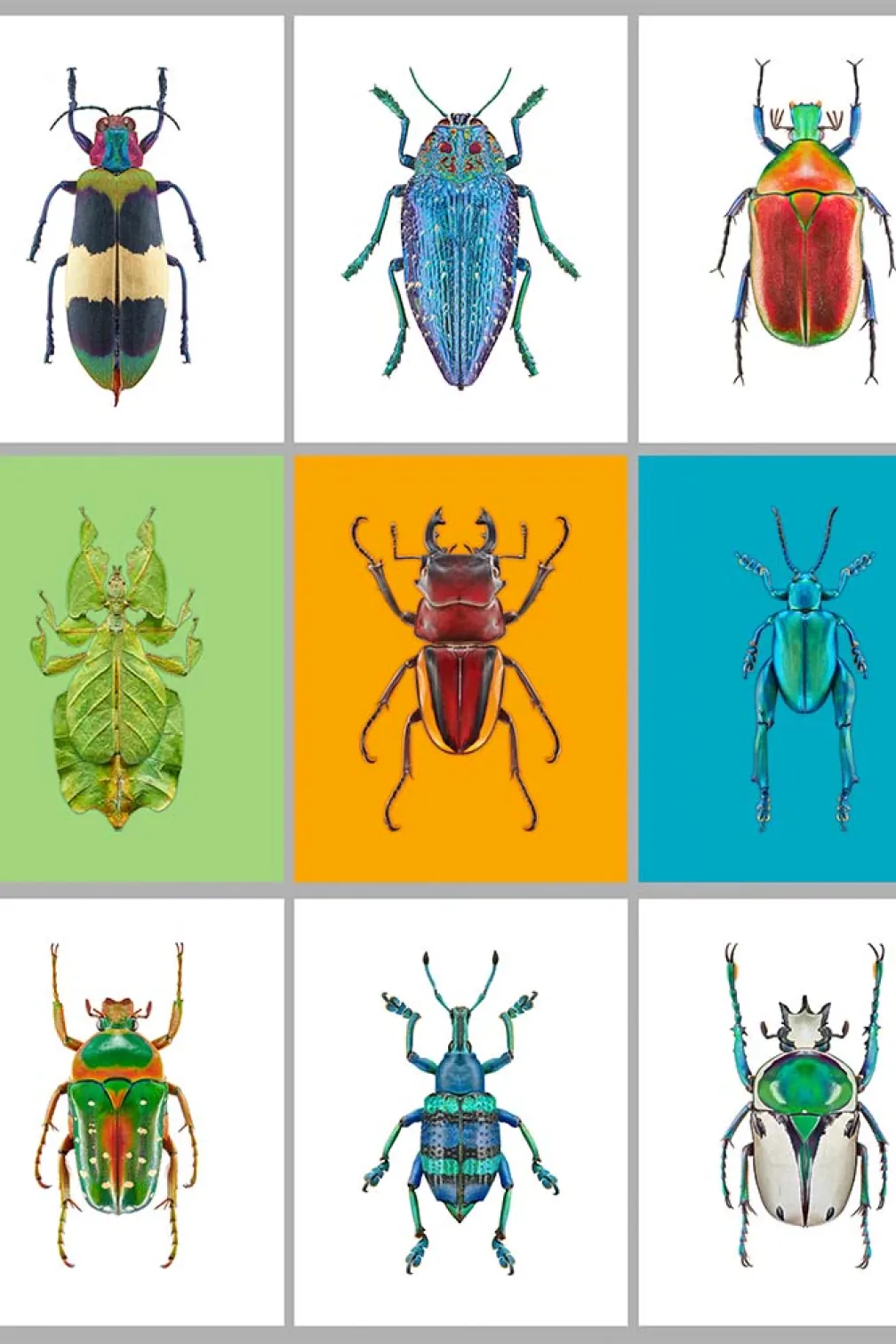

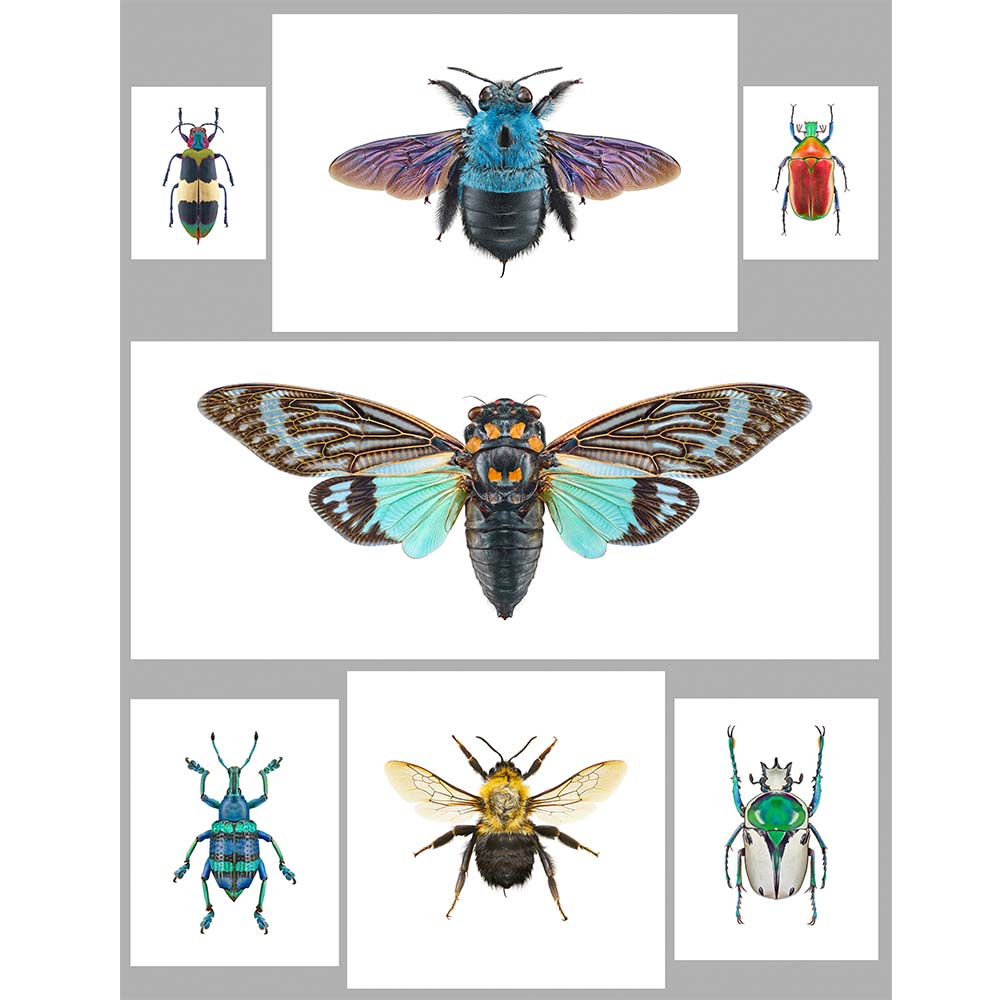

On His Side Hustle Photographing Beetles

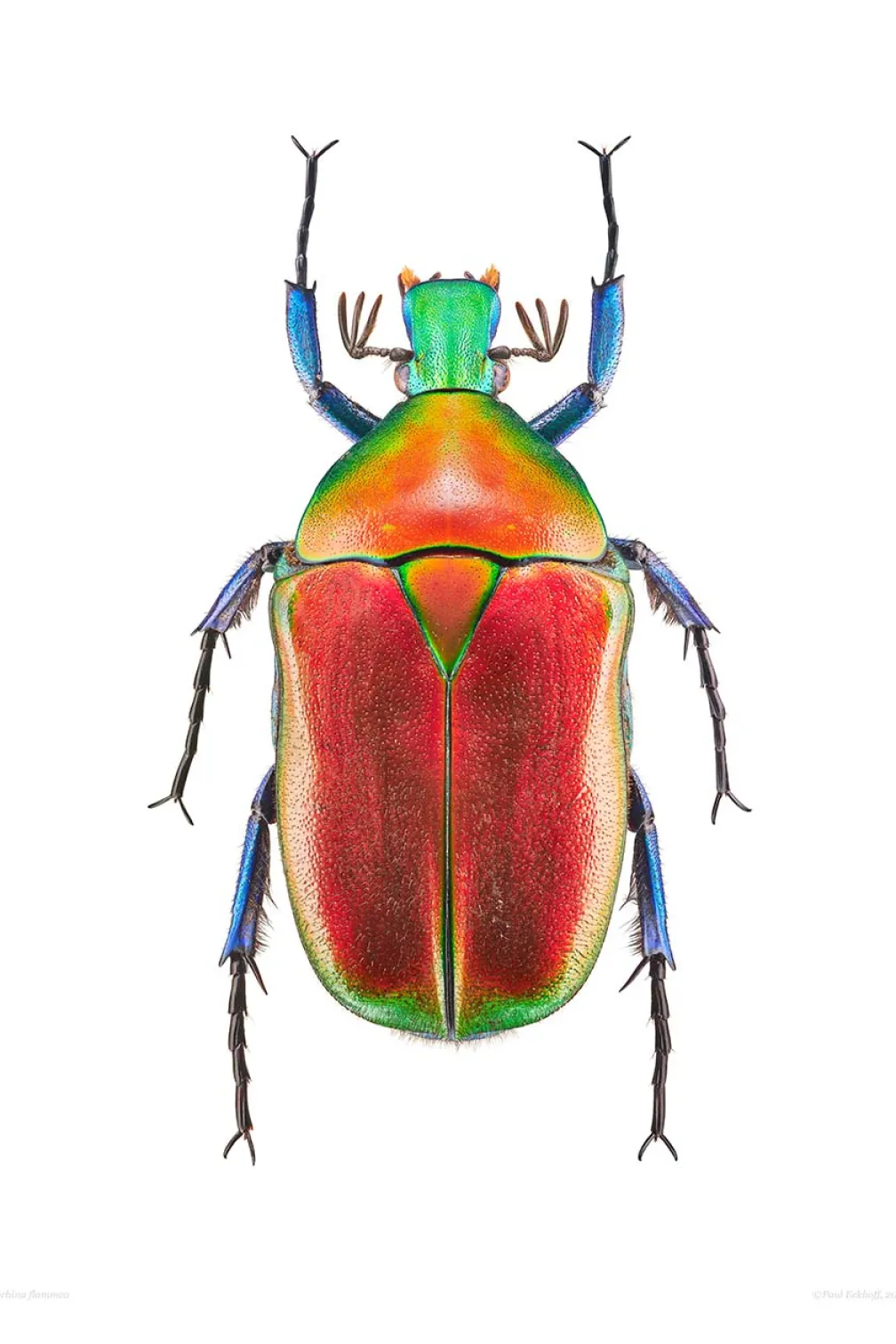

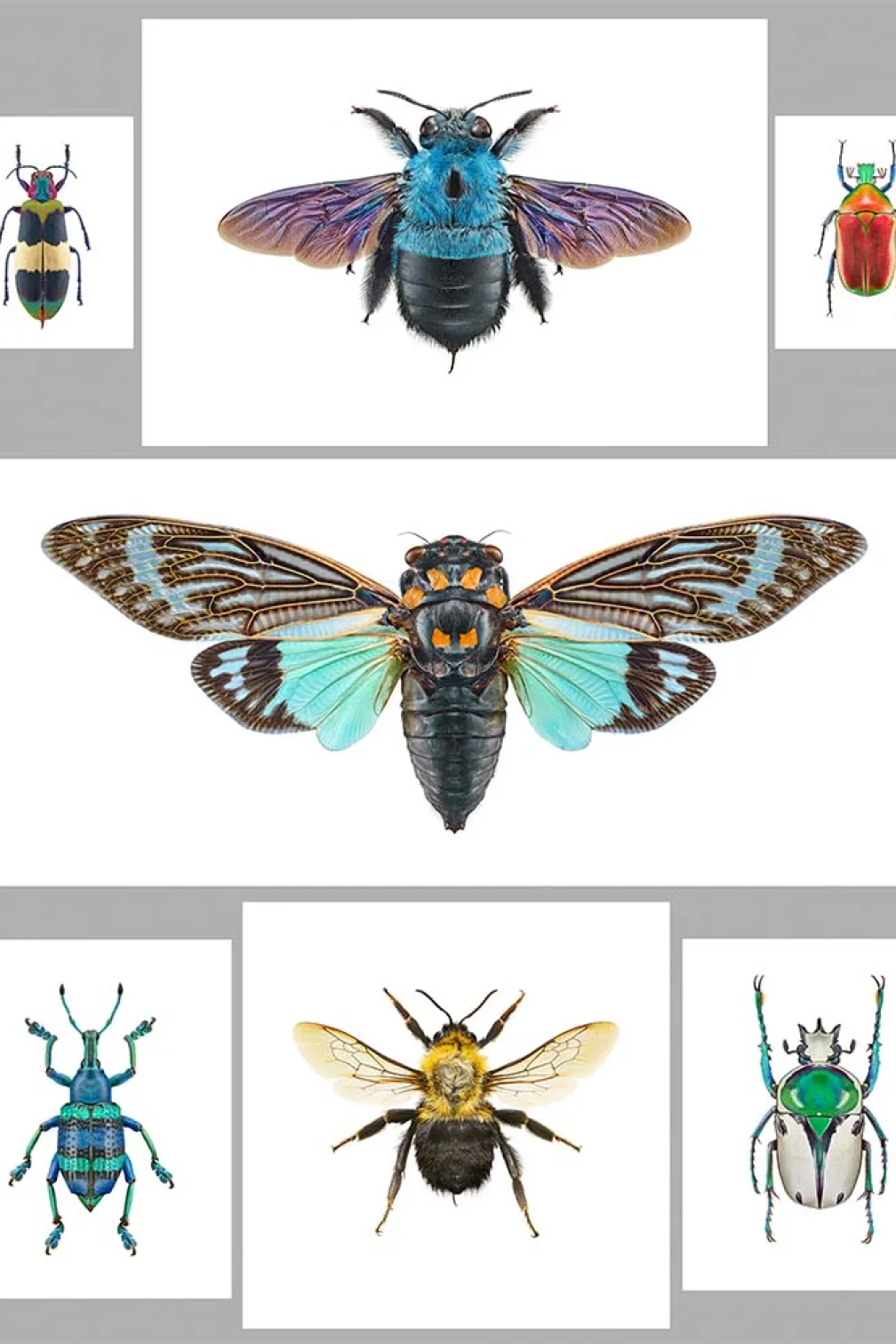

Back in the 2000’s, during the early days of digital photography, Eekhoff worked as a consultant for the camera company Olympus. On a work trip to New York City, he happened upon a shop in Soho called the Evolution Store, which sells everything from taxidermied skunks to 3D gorilla puzzles. Inside the store, behind glass frames, was an array of beautiful, brightly coloured beetles.

“Oh my god,” he remembers thinking. “I’ve never seen that before.”

After openly gushing over the beetles, Eekhoff was escorted upstairs by the owner to a room with dozens of cabinets filled with beautiful insects. Stunned, Eekhoff asked if they were for sale. They were. So, he bought some beetles and brought them across the border—an “interesting” experience, he said—to his home studio.

At first, he was stymied by his printer’s inability to capture some of the beetles’ red and ochre colours. But he returned to the project in 2008 and soon began to develop a body of work.

Gallery 2

Then I just submitted my work to a couple of art shows,

“Then I just submitted my work to a couple of art shows,” said Eekhoff. “I needed to get a public response to make sure I wasn’t completely wasting my time photographing these insects.”

The shows were an unexpected success. So, Eekhoff began debuting the photographs at galleries and selling prints of his work. Of the many reactions he got, the most common was bewilderment.

“They all asked the same question,” he said, smiling. “What am I looking at? I know it’s a bug, but is it a high-resolution painting or a photograph?”

Eekhoff, who cited the botanical drawings of the “Dutch masters” as an influence, was delighted by the confusion. “I just love it,” he said. “I get so excited that people are bemused by the ambiguity.”

During our conversation, I suggested perhaps that’s because his work lives at the intersection of art and science, between photography and painting.

He paused, thinking.

“I like that.”