Re-enactment, Archaeology, and the Ancient Rome & Greece Weekend III of IV: The Dagger

Published

Categories

Author

Blog Post

So in my project to recreate the equipment of a 3rd century Roman soldier from Dura-Europos, following the creation of the sword, I next moved on to the dagger. Little seems to be known about the daggers used by soldiers in the Roman World of the 3rd century AD. The well-known dagger of the Early Roman Imperial period, the "pugio" , was a very broad dagger with a central ridge. It is well represented in finds and is often shown in contemporary depictions suspended vertically from the military belt on the left-hand side. However, by the time of Dura-Europos in the mid-3rd century we find very few "pugiones", there is only one fragment from the site itself, and they are not depicted on soldiers of the period. There was a find at Künzing, Germany of about 50 pugiones in a cache dated to about 250, but it is thought that these may actually be outdated equipment by some authors (the broad blade would probably not be ver effective against the heavily-armoured horse-man, or cataphract). However, one of the reasons they might not be depicted is because soldiers of the time are always shown wearing the military cloak, which often drapes over the left shoulder (the wall-painting of Julius Terentius from Dura-Europs being a typical exampe), and the sword is now also hung on the left-hand side from a shoulder-strap. The cloak and sword would thereby obscure the pugio if it was hanging where it had traditionally been worn. But still, given the archaeological scarcity of the pugio, it seems another type of dagger should be considered (it seems to me unlikely that any soldier would ever do without this last-ditch defence).

A replica of a 3rd century Künzing-style pugio, above (acquired from Armamentaria), and the hypothetical reconstruction of the Budapest dagger, below (made by Tod) - photo by Kay Sunahara.

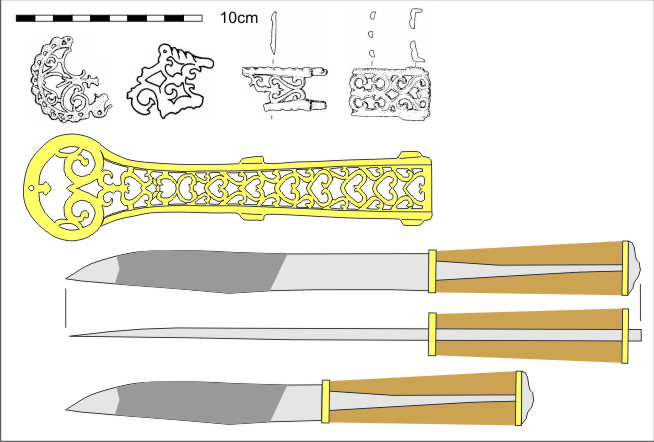

On a number of later sites in the Roman Empire, copper-alloy plates for dagger or knife scabbards of a very different nature are found, more complete examples showing a spatulate (spoon-shaped) end. Four fragments were found at Dura-Europos, shown in the drawing below, with my own drawing of a very similar but more intact scabbard plate from Budapest in Hungary. The Budapest find came with other fittings and the fragmentary remains of a blade. Unlike the wide two-edged pugio, the Budapest blade is single edged and narrow, with an angled back and a curved edge. It has been suggested by others that the Budapest blade would have been quite short and most of the dagger, including the grip, would fit inside the scabbard, much like the daggers of Northern Europe beyond the frontier at this time. However, although the blade is of course corroded, and probably thicker than it was originally, it is quite thick, thicker than a small knife would need to be. Also, the scabbard plate is flat, suggesting it would be intended to contain something that is equally flat, like the blade alone, which would indicate that if this was a knife scabbard the blade would be as long as the plate. For people studying Roman weaponry and accustomed to the pugio it may seem like a very narrow blade indeed, but this would be about the size and thickness of a Mediaeval fighting knife. In the drawing below is a reconstruction of a short dagger, and the longer dagger that I am proposing actually went in these scabbards. The grip is based on finds of Roman daggers from a bog deposit at Nydam in Denmark which had been preserved in the waterlogged conditions. The reconstructed longer blade is very interesting, as it would seem to be descended from the curved "sica" dagger which was widespread in the Balkans in the 2nd-1st century BC, and it also seems ancestral to the Navaja of Spain. This point interests me because of my interest in the Middle East, and background reading I did when I was an ambassador for the ROM's Dead Sea Scroll exhibition some years ago, when I travelled Ontario talking about the scrolls and their context. In the Roman period, the sica was a notorious weapon, and "sicarii" were assassins and bandits. The historian Josephus used the term in 93 AD to describe a group of Zealots that used assassination for political purposes. Little seems to be known of what these sica actually looked like, although because they were concealed they are sometimes hypothesized to be "small" or "short" by present writers. But if this knife from Budapest is a sica, it makes more sense, as it is a very effective and deadly fighting knife.

Drawings of the four fragments of dagger scabbard plate from Dura Europos (top - after Simon James' book on the finds from Dura ) and a reconstruction of a more complete plate from Budapest, Hungary (after a drawing by Sellye Ibolya). Below are two hypothetical daggers based on the fragment from Budapest (darker part of blade), one that fits almost entirely in the scabbard, one in which only the blade fits in the scabbard.

Finds of these scabbard plates from Intercisa (modern Dunaujvaros, Hungary) and Augusta Raurica (modern Augst, Switzerland) seem to indicate that the scabbard was suspended horizontally from two points on the left hand side. The pugio was also suspended by rings attached to the side of the scabbard, although in this case there are two on *each* side allowing it to be hung vertically from the upper rings, or hypothetically from two side rings allowing it to be worn horizontally (there is much discussion amongst Roman military historians about why the pugio has so many rings, although it is only depicted as hung vertically, and studies of wear by use indicate vertical hanging).

A replica of a 3rd century Künzing-style pugio, above (acquired from Armamentaria), and the hypothetical reconstruction of the Budapest dagger, below (made by Tod), both in their scabbards - photo by Kay Sunahara.

I sent the published drawings of these finds, and my drawings of the hypothetical dagger, to "Tod" Todeschini who made the replica Dura sword, and the result may be as seen above (the wooden grip is actually made of Roman wood - from pilings preserved in the waterlogged Thames). The horizontal hanging being explored by this construction now makes a lot of sense. The spoon-shaped end counterbalances the grip and allows it to balance perfectly at the suspension rings. Assuming that the user is right handed, the scabbard would be hung on the right hip, or on the back. This would mean that the knife is out of the way of the saddle when riding, very important for the horse-riding soldiers of the time. Of course, if this knife is hung on the back, it would explain why it is never depicted, being always concealed by the cloak, but even if it was on the right hip it would not be obvious in the painting of Julius Terentius. The term "concealed" of course now becomes very interesting if this dagger was called a sica by the Romans. If this hypothesis is correct, this narrow but deadly fighting knife might have been carried out of sight by its very nature.

.

Here the scabbard and knife are suspended by a cord, showing how the spatulate end acts as a balance to the dagger if it is of the longer blade type that I have hypothesised. I would question that a short blade would create this balance, which would be important if, as the evidence suggests, the scabbard was worn horizontally - photo by Kay Sunahara.

So if you come to Ancient Rome & Greece weekend on June 15th you can see the hypothetical reconstruction of the Budapest knife in person, or not, if I have it concealed! Since the scabbard plate is so elaborate, it is highly unlikely that this object was made to be hidden. However, as often happens in the archaeological record, these scabbard plates may be the preserved examples of a class of objects more typically made of materials less resistant to corrosion or rot - for instance iron. The scabbards of the Künzing pugiones, for instance, would be poorly regarded fragments of rust if they were as fragmentary as most of these copper-alloy scabbard plates were.

The knife is certainly the most contentious of the recreations, but as Simon James says in his book on the Dura-Europos finds: "no simulation or visual reconstruction, at least of any complexity, may ever be regarded as 'correct' or 'definitive'; they are always provisional and, to some extent, wrong: the only issue is, how wrong are they?"

This assemblage of reproductions shows a Künzing-style pugio, above (acquired from Armamentaria), a mediaeval fighting knife - known as a ballocks dagger, and the hypothetical reconstruction of the Budapest dagger, below (both made by Tod). The mediaeval dagger is quite large for its type, but you can see it is much closer to the Budapest reconstruction. These narrow knives may be considered rather small to anyone accustomed to the pugio, but the pugio similarly looks large and unwieldy to a mediaevalist! It is possible that the narrower knives would be more useful getting into the chinks between the greater coverage supplied by the armour of their periods - photo by Kay Sunahara.