Mystery of conical fossils solved, after 175 years

Published

Categories

Author

Blog Post

My name is Joe Moysiuk, I am a 20-year-old undergraduate student at the University of Toronto enrolled in both the departments of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology and Earth Sciences. I am excited to announce that a research paper which I am lead author of, titled Hyoliths are Palaeozoic lophophorates, has recently been published by the journal Nature This paper was based primarily on newly discovered fossils housed in the ROM’s invertebrate palaeontology collections.

Adding a new branch to the tree of life

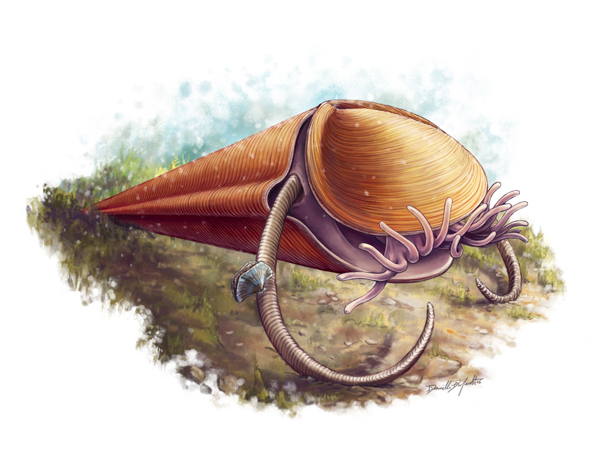

For the past year and a half, I have had the opportunity to collaborate with Dr. Martin R. Smith of Durham University and Dr. Jean Bernard Caron of the ROM. The subject of our research was an extinct group of cone-shaped marine organisms called hyoliths. Hyoliths were some of the first animals to evolve a mineralized external skeleton – comprised of upper and lower shells and curving spines – during the Cambrian Explosion (starting about 542 million years ago). Fossilized skeletal remains of hyoliths are abundant around the world, and demonstrate that these animals existed for about 280 million years during the Palaeozoic Era, but they became extinct around 20 million years before the appearance of the first dinosaurs. Despite their excellent fossil record, little was previously known about where hyoliths fit in the tree of life – a palaeontological mystery that persisted for over 175 years since their discovery. In our paper, my coauthors and I present exceptionally preserved hyolith fossils from the Burgess Shale, complete with their internal soft anatomy preserved. Newly described features, in particular a band of feeding tentacles, reveal a surprising evolutionary relationship between hyoliths and a group of animals called lophophorates (whose living representatives include brachiopods and phoronid worms). For more information about hyoliths and our research, see our press release.

How I got involved in palaeontology at the ROM

I have been captivated by palaeontology from a young age. My interest began when I first noticed the abundant marine invertebrate fossils preserved in the rocks of Toronto’s ravines. My parents indulged my curiosity with frequent trips to the Rock, Gem, Mineral, Fossil and Meteorite Identification Clinics at the ROM, where I could bring in the fossils I found and learn more about them from the ROM’s experts. These early interactions with ROM invertebrate palaeontology researchers – in particular (now retired) Assistant Curators David Rudkin and Janet Waddington – were my earliest inspiration to pursue a career in this field, highlighting the vital role that museum outreach can play in nurturing young researchers.

During high school, I was able to secure a co-op education placement in the ROM’s awe-inspiring invertebrate fossil collections, working closely with Technician Peter Fenton on a wide variety of projects relating to collection upkeep and research. Since then, I continued learning about invertebrate palaeontology and the ROM’s collections, first as a volunteer, then as a contract employee and eventually as a student researcher. In all, I have been involved with the ROM’s Invertebrate Palaeobiology Section for about four and a half years.

Burgess Shale research

As a result of my work at the ROM, Dr. Caron, ROM Senior Curator of Invertebrate Palaeontology and an expert on the Cambrian Explosion and Burgess Shale fossils, recruited me to participate as a volunteer in the 2014 summer field expedition to this world-renowned fossil deposit in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia. The Burgess Shale is remarkable for its exceptionally preserved fossils of soft-bodied marine animals, which lived approximately 508 million years ago (see the ROM Burgess Shale website for more information on this amazing fossil treasure). The 2014 expedition was to the recently discovered Marble Canyon locality, about 40 km from the original Burgess Shale site, in Kootenay National Park. See Dr. Caron’s ROMblog post to read about the discovery of Marble Canyon.

At Marble Canyon, we opened a quarry to access the richest fossil-bearing shale layers, continuing from work at this site in 2012. The rock does not give up its secrets easily, but the payoff is well worth the effort. The sheer abundance of fossils at Marble Canyon is staggering, with hundreds of specimens uncovered on the best days. On top of that, extraordinary discoveries that reveal new aspects of extinct organisms, or even entirely new species, occur with surprising frequency. The thrill of splitting open a piece of shale to reveal a 508 million-year-old fossil, the likes of which may never have been seen before, is incredible and addictive. This atmosphere of excitement, along with the beautiful setting in the mountains of Kootenay National Park, drew me to return to the Marble Canyon area with Dr. Caron in the 2015/16 seasons of field work.

The many spectacular discoveries that have already been published as a result of the fossils found at the Marble Canyon site represent just the tip of an iceberg, with many years of additional work expected to come. See the following links for details on other Marble Canyon research: Metaspriggina; Yawunik; Oesia; Surusicaris.

Last spring, I completed a year-long credited U of T research project (Research Opportunity Program – EEB 299) with Dr. Caron as my project supervisor. Hyolith fossils, particularly the new specimens which I helped to collect, were the focus of my project. When I started this project, my aspiration was to eventually present the results as a peer reviewed paper, in collaboration with Dr. Caron and Dr. Smith. Over the year, I studied all of the more than 1500 hyolith fossils at the ROM. This included mechanically preparing some specimens. Preparation is a delicate task that involves working under a microscope while using a small pneumatic chisel to expose still buried portions of the fossil, and it forces one to observe the smallest preserved details. Dr. Caron also trained me in the techniques of light and electron microscopy used to observe fossils.

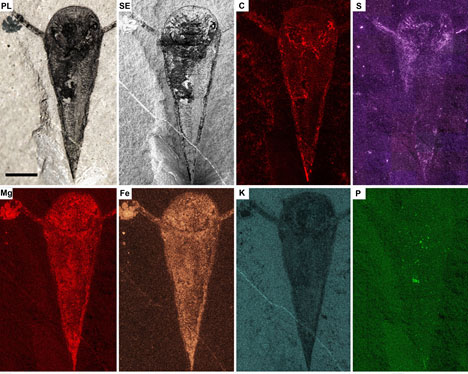

I was privileged to have had the assistance of Sharon Lackie of the University of Windsor, who was able to produce maps of the distribution of elements in our hyolith fossils. I also had the opportunity to collaborate with talented palaeoartist Danielle Dufault at the ROM, who produced some incredible hyolith reconstructions. At the end of the Research Opportunity Program, I drafted a manuscript, which became the foundation for our paper. I spent much of my summer and fall working with Dr. Smith and Dr. Caron to refine the paper and prepare it for submission, and after peer review, for publication.

Next steps

In December, I presented our new hyolith discoveries at the Palaeontological Association Annual Meeting in Lyon, France. Our poster was the recipient of the Annual Meeting Council Poster Prize. I will soon be highlighting our study to the public at this year’s ROM Research Colloquium in February (stay tuned for more details on the ROM website). I look forward to further sharing our amazing new findings in the upcoming months!

I have been fortunate to have had many opportunities to develop my interests in invertebrate palaeontology, but I’m not the only one who has benefited from such interactions at the ROM. Dr. Caron has supervised a number of U of T graduate and undergraduate students (including my co-author Dr. Smith, a number of years ago). The high level of professionalism, enthusiasm and world-class expertise displayed by Dr. Caron and my fellow students in his lab at the ROM is inspiring to be a part of. I look forward to continued research interaction at the ROM, as I begin a new project with Dr. Caron on yet another group of intriguing fossils from Marble Canyon.

An exciting initiative in development at the ROM is The Dawn of Life Gallery, which will publicly display a unique showcase of fossils and research discoveries from across Canada, and the world – ranging in time from the beginning of life on Earth to the first dinosaurs. The work of my colleagues and I is one aspect of this larger story, and I hope that it can contribute towards making this the best gallery of its kind, and to cultivating the next generation of palaeontologists.

Publishing a research paper has been my long-term goal for many years and it is very gratifying to have been able to bring the hyolith project to a published conclusion. I am thankful to my coauthors and collaborators, to the ROM and the U of T (Victoria College and the Departments of EEB and ES) for helping to facilitate my research and to family, friends and professors who supported and encouraged my passion over the years. I would also like to thank NSERC (though Dr. Caron), the U of T Arts & Science Student Union and the Palaeontological Association for conference travel funds.