An Innovative Approach to a Puzzling Problem: The Conservation Treatment of an Indian Chintz Cope

Category

Audience

Age

About

After many months of preparation, the ROM’s latest exhibition, The Cloth that Changed the World: India’s Printed and Painted Cottons, has opened in the Patricia Harris Gallery of Textiles and Costume.

Among the many objects chosen for the exhibition one posed a particular challenge to conservators.

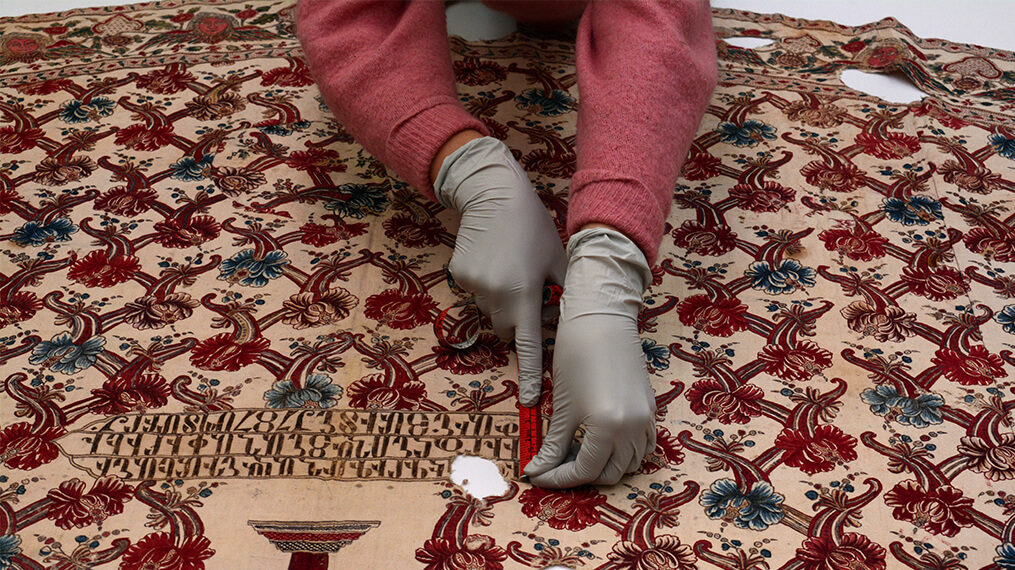

Created in India in the 18th century, for a Christian priest working in Armenia, this liturgical garment, known as a cope, was a gift from the priest’s parents and is included in the exhibition as an example of the wide dissemination of the Chintz artform.

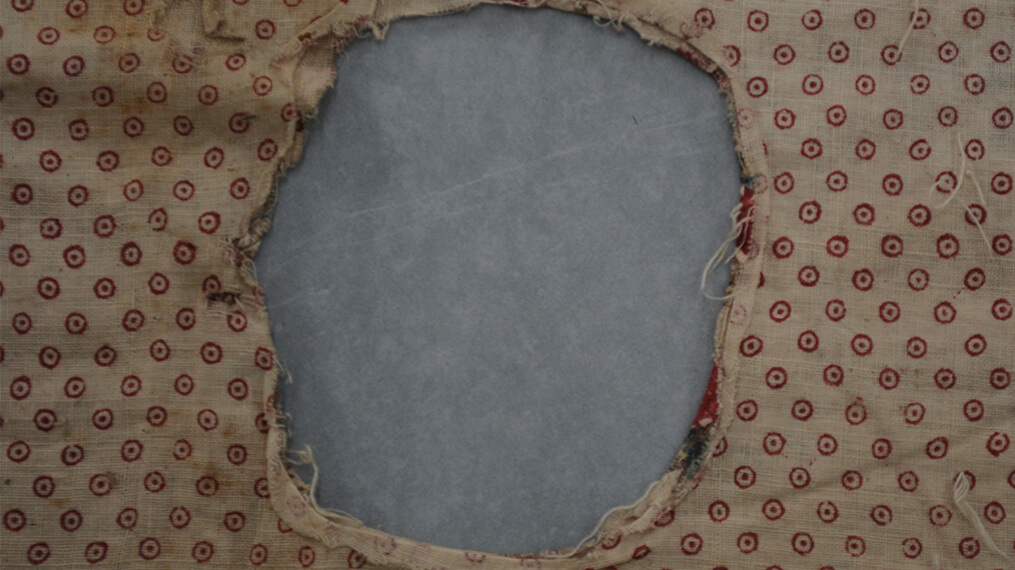

The cope was brought to the Textile Conservation lab for a preliminary examination in the fall of 2018. Despite its considerable age, the fabric of the cope was still in sound condition though with some scattered staining and signs of wear; the colours still vibrant. There were however several large holes which appeared to be cut out of the fabric.

Most areas of loss included both the outer layer of the cope as well as the lining. Some holes had been previously repaired (no record exists of when this may have occurred or by whom) with patches applied to the lining layer only.

In order to stabilize the holes and prevent further damage, these areas of loss would be supported by the application of fabric patches between the outer layer and the lining.

The large size of the holes made them visually distracting and patching with a colour-toned neutral fabric, a common conservation practice, would leave large gaps in the pattern on the textile.

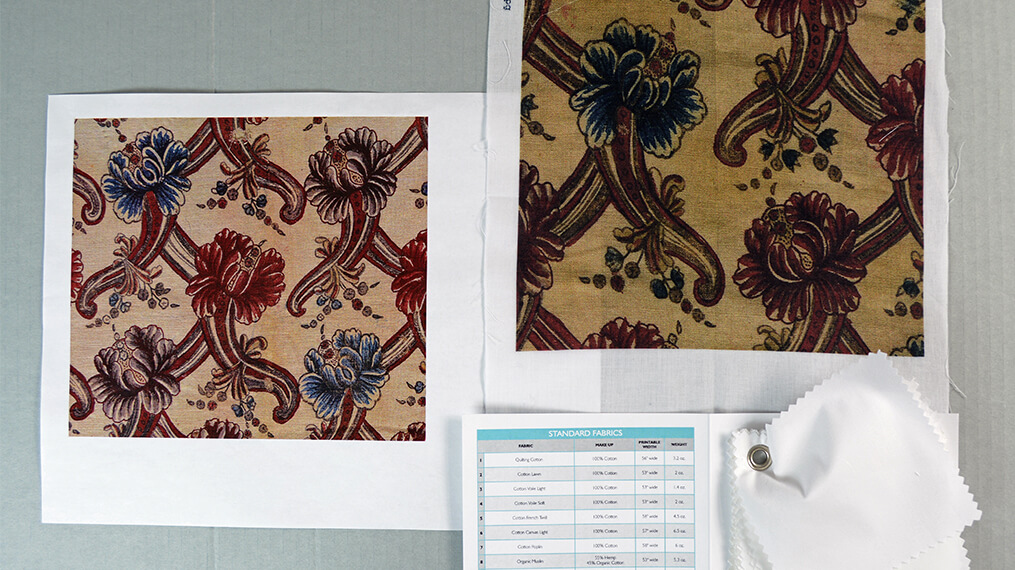

After consulting with colleagues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Canadian Conservation Institute in Ottawa, ROM conservation staff chose digital textile printing to recreate the missing areas of the design.

Inkjet printing recreates an image by propelling tiny jets of ink onto a substrate. In this instance, a digital image or scan of the surface design is uploaded to a computer which operates a wide format fabric printer. The printer uses dye or pigment-based inks.

In order to achieve the most accurate reproduction of the textile surface design the digital image must be manipulated in two ways. The image must be scaled to a 1:1 ratio with the original object followed by a process of colour matching.

The preparation of our images was undertaken by Lara Morrison, a recently graduated Textile major in the Bachelor of Craft and Design program at Sheridan College.

Working with ROM Textile Conservator Anne Marie Guchardi, Lara took measurements of design motifs on several undamaged areas of the cope’s surface.

She then compared these measurements to the size of motifs previously photographed by the ROM’s photography department and adjusted the images to achieve the correct scale.

Achieving an accurate reproduction of the colours of the cope’s design proved extremely challenging and involved calibrating an image using digital imaging software, uploading the images to the printing company website and generating test swatches which were then matched to the original.

This process was repeated several times until an appropriate match was achieved.

Once acceptable images were selected they were reproduced on fabric and the fabric processed to achieve suitable washfastness.

It comes as no surprise that objects age over time and a 250 year old textile is no exception. Producing a printed support patch which could reproduce the staining, uneven discolouration, and individual paint strokes of the original took considerable effort. In some cases, printed patches were further enhanced with fabric paint.

Once the support patches were ready it was time to prepare the cope for repairs. In most cases the edges of the large holes in the cope’s surface had been pressed under.

Controlled humidification of the surface and the application of light pressure coaxed the folds open. In some cases, a remarkable amount of original fabric was revealed.

Patches were prepared from the digitally printed fabric, gently inserted into the holes between the outer surface and the lining, and the pattern was aligned.

The patches were secured around the perimeter of the holes with hand stitching using a curved surgical needle and fine silk thread.

x

The patches were secured around the perimeter of the holes with hand stitching using a curved surgical needle and fine silk thread.

x

Conservation treatment of the cope, from initial condition assessment to final mounting for display involved approximately 500 hours of work over a period of one year.

While the digital replication of the areas of loss in the cope could not completely reproduce the uniqueness of the original chintz artist’s design, the overall results are quite satisfying and allow the eye of the viewer to focus on what is present rather than what is absent.

I would like to thank the following people for their generous contributions of time and expertise to this project:

- Senior Conservator, Textiles, Chris Paulocik, Royal Ontario Museum

- Senior Curator, Global Fashion and Textiles, Sarah Fee, Royal Ontario Museum

- Conservator, Nancy Britton, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Lara Morrison

- Oleg Sokruto, Preparator, Royal Ontario Museum