What Do Our Collections Do

Published

Categories

Author

Mass Extinctions. Pandemics. Climate change

Mass Extinctions. Pandemics. Climate change. Today, Earth faces an array of interlocking crises with potentially devastating consequences. But for humanity to respond effectively, we must first understand these problems in all their vast complexity.

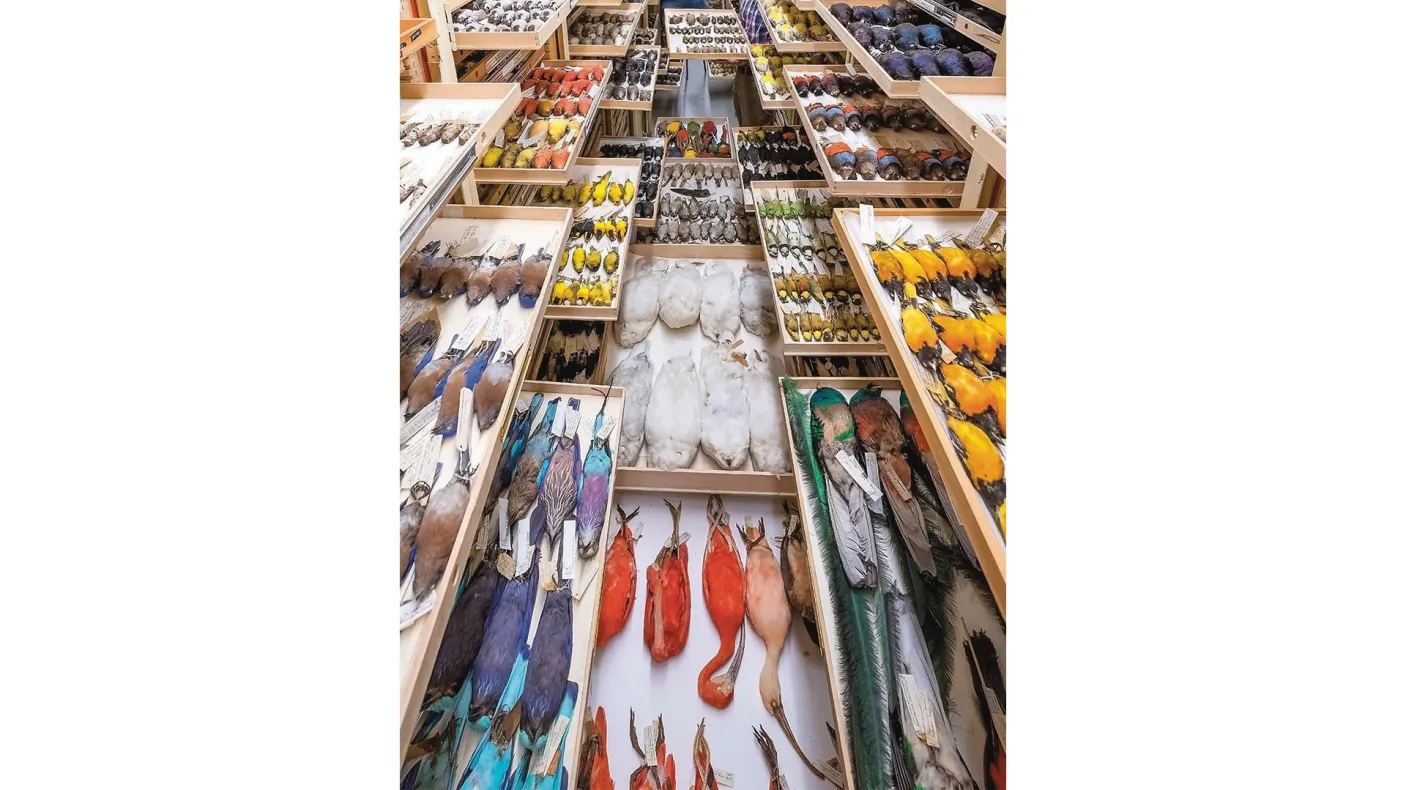

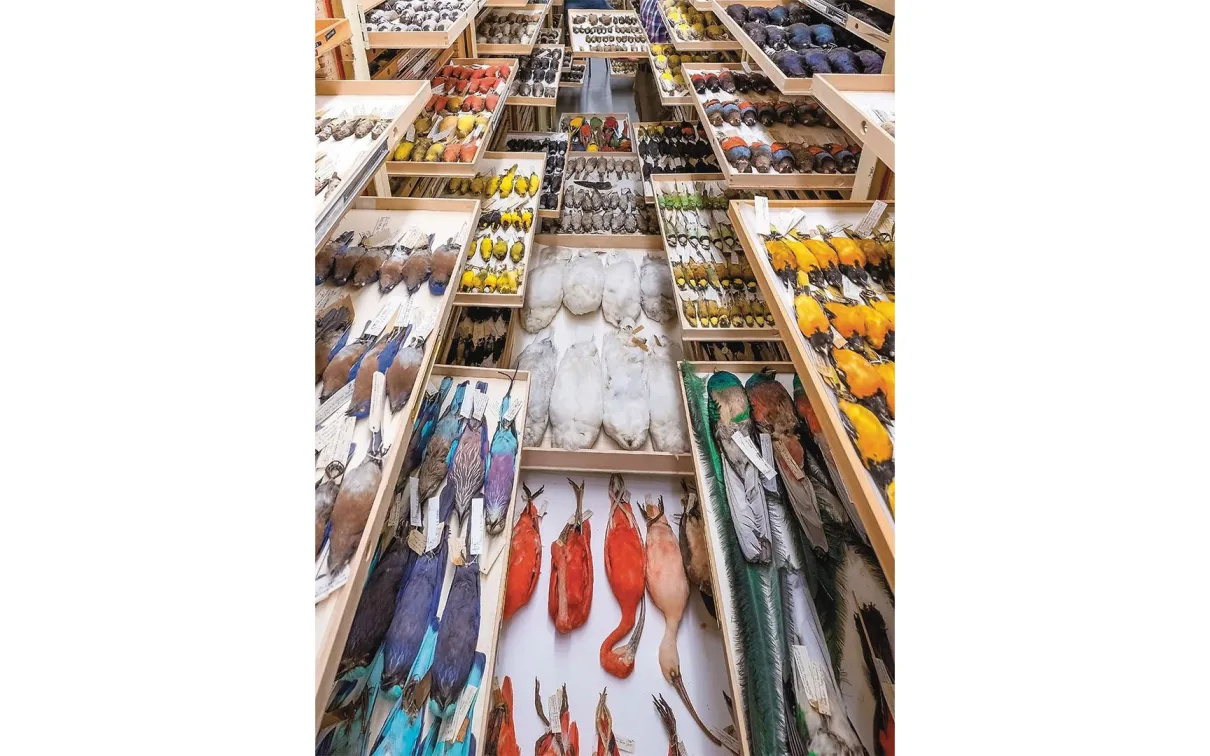

That’s where natural history collections come in.

Combined, these collections inform much of what we know about the natural world—and our place in it. Take pandemic preparedness, for example. Museums, including ROM, are home to myriad species of bats. Some of those specimens are being screened for coronaviruses like SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19. When found, those viruses can be extracted and studied, so we can stop the next pandemic—before it even starts.

Natural history collections are also essential for understanding and protecting biodiversity. As Earth warms and more and more habitats are destroyed, museum specimens act as a baseline of biological and ecological health, informing everything from local conservation efforts to global policy.

But there’s a problem. As a group of contributors—including Josh Basseches, ROM Director and CEO, and Dr. David Evans, Co-Chief Curator of Natural History and the James & Louise Temerty Endowed Chair of Vertebrate Palaeontology—noted in a recent paper in Science, “The information embedded in the collections housed in these museums is largely inaccessible.”

So, a group of 73 major museums with natural history collections, led by a core of 12 public-facing museums including ROM, established a framework that can “map the aggregate holdings of the global collection.”

Between the 73 museums, more than one billion objects spanning billions of years and every continent on Earth were inventoried, Revealing “many gaps, challenges, and opportunities.” The database is now available online, where anyone can easily download and filter the data.

“Work now needs to happen at a pace and magnitude that will meet the urgency of the Anthropocene,” the authors of the Science paper wrote, “with the understanding that there are more species at risk of extinction than are currently known to science.”