Art, Fashion, and Kalamkari Makers

Narratives on untailored cloth.

Published

Category

Author

Cloth in Art, Cloth in Fashion

Folded kalamkari fabrics in dye artist Ajit Das’s workshop possessed an innate ambiguity: when folded, they are pieces of fabric; when unfolded, they reveal themselves as a hanging, scarf or a sari. For generations, kalamkari makers have excelled in the skill to nurture as well as explore this ambiguity of untailored fabric. Folded, packed as cargo, three such contemporary chintz textiles were sent to the ROM to be displayed as part of the Cloth that Changed the World: The Art and Fashion of Indian Chintz, echoing the centuries of interregional movement of the dyed cottons of India (See Barnes 2020, 72-81; Crill 2020, 106-35). Das’s monumental hanging Prosthor along with master kalamkari maker Malipuddu Kailasham’s ambitious Sitamma sari and Kailasham’s guru the late Aithur Munikrishnan’s Sai Baba hanging—a unique amalgamation of temple hanging and comic strips—share the gallery space with historical as well as contemporary textiles celebrating the manufactural and utilitarian multiplicity of the Indian chintz. Das, Kailasham and Munikrishan’s narratives are dyed onto essentially large rectangular untailored pieces of handwoven cotton, moulded into objects of art as well as fashion. How does the untailored cloth allow textile makers to intermediate between art and fashion?

Humble in appearance, plain woven fabric is replete with possibilities and mobility offering artisans to experiment and expand the parameters of their knowledge practice. As Roland Barthes argues, parasitic elements in fashion, circular or tenuous objects of clothing, and tailored goods with “supervised freedom” limit variation and scopes to experiment (Barthes 1990, 176-8). The unstitched cloth challenges all three determinants and endures to transitions.

Transition in the realm of contemporary dyed textile making in India has manifested into an engaging critical discussion. Divia Patel stresses that the artisan-artist/designer collaborations in the last three decades in India thrived on deconstructing community-based patterns, reviving historical imagery design innovation as well as technological interventions (Patel 2020, 265-8). On the other hand, Eiluned Edwards delineates how organizations and dynamic individuals have assisted the Ajrakh block printers of Dhamadka to evolve from making caste-dress to unique items for home furnishing (Edwards 2020, 242-6). Uniqueness in the late twentieth century, as Alexandra Palmer delineates, stood on the ability to respond to, negotiate or reject the norms set by the fashion industry (Palmer 2020, 253-63). Adding to these compelling accounts, I will present narratives in which artisans themselves sook a middle ground to operate between craft/art and fashion.

Narrating on Cloth, Narrating with Cloth

In many ways, Prosthor presents a condensed version of Das’s layered and devoted practice of natural dyeing. This large vertical hanging depicting three meticulously executed balancing rocks against a muted background evokes a strong connection to abstraction as well as the narrative richness of kalamkari. Belonging to a family of washers and dyers in the northeastern Indian state of Tripura, Das worked for thirty-four years with the Weavers Service Centre (WSC) starting in the 1980s which enabled him to travel various towns and cities with rich textile histories such as Ahmedabad, Jaipur and Srikalahasti among others and assimilate the various techniques of natural dyeing into his practice. Abstraction in Das’s practice emerges as a strategy to reveal the sedimentation of varied dyeing techniques from western and southern India as well as to consciously distance himself from so-called traditions. The drive towards abstract imagery gained momentum in the WSC under the supervision of the prolific textile activist Martand Singh—popularly known as Mapu. The calculated patches of dry brush and stippling to build the rock surfaces derives from his long-term experimentation with the density of dyes, block printing and introducing differences in repetitive motifs. The unmistakable balance between the three rocks—as he commented during an interview in his Kolkata residence in January 2021—developed from a keen observation of rock structures in the Deccan plateau reflecting his strive to strike a balance between family life and profession early in his career.

Themes of Das’s hangings and wearables are often overlapped. Das’s recognizable visual elements, such as linear intricacy and balanced compositional arrangement in Prosthor were exercised onto scarves and wearables at least since the 1990s. Myrobalan treated rectangular scarves and saris provided him grounds for visual experimentation—similar to that of the hanging but different in purpose. While recalling a commissioned project of making kaftans, Das stated, “it is impossible to mordant-paint stitched garments. We sewed two dupattas and made openings for neck and hands for each kaftan and then, unstitched them.” I envisioned the unraveled kaftan material on Das’s long drawing table being prepared for mordant painting alongside his celebrated hangings.

In 2020, he created a sari depicting tigers

In 2020, he created a sari depicting tigers in a forest landscape. The sari reflects Das’s eye for detail, a balanced yet playful compositional arrangement complemented by a selective colour palette, also evident in Prosthor. However, Das tweaked the compositional elements keeping the utilitarian aspect of the sari in mind; for example, the jumping tiger (in right) is intended to appear within the pleats in front mimicking a folding screen.

The narrative potentials of the sari are also explored in Kailasham’s Sitamma sari. A kalamkari painter trained under A. Munikrishnan of Srikalahasti, Kailasham draws narrative hangings and ornamental dressing material with equal ease.

Renewed direction

Kailasham’s practice found a renewed direction with his move to Hyderabad to work with the WSC, initially situated at Karwan, close to the river Musi. Unlike Das, he only worked part-time with the Centre until setting up his workshop in the Langer House area. As Kailasham stated during an interview in Hyderabad in June 2019, proximity to the river was a prime factor for him to settle in Langer House. The river supported his dyeing endeavours until recent times when the water turned inutile due to increased pollution. When asked to prepare a sari for the ROM, Kailasham expressed interest to transplant an episode from the Hindu epic Ramayana into it, following artist J. K. Reddayya from WSC.

This sari registers a decisive moment of the epic where Guha, a boatman, takes Rama, Sita and Lakshmana across the river Ganges at the beginning of their fourteen-year banishment. While he diligently followed the iconographic details and established commitment to the conventional temple hangings by inscribing the episode in Telugu in the pallu, Kailasham chose to stress on the river, aquatic lives and a forest of Deccani motifs. The river here serves a twofold purpose: it transforms into the wide lower border of the sari and stands as a metaphor for the fluidity that Kailasham has infused into the narrative mix. I also wondered if his association with the river Musi bolstered his creative decision of emphasizing the river and riverine landscape. The rectangular ground of the sari empowered his clever decision to move beyond the framework of the narrative hanging yet staying true to his training.

Compartmentalisation

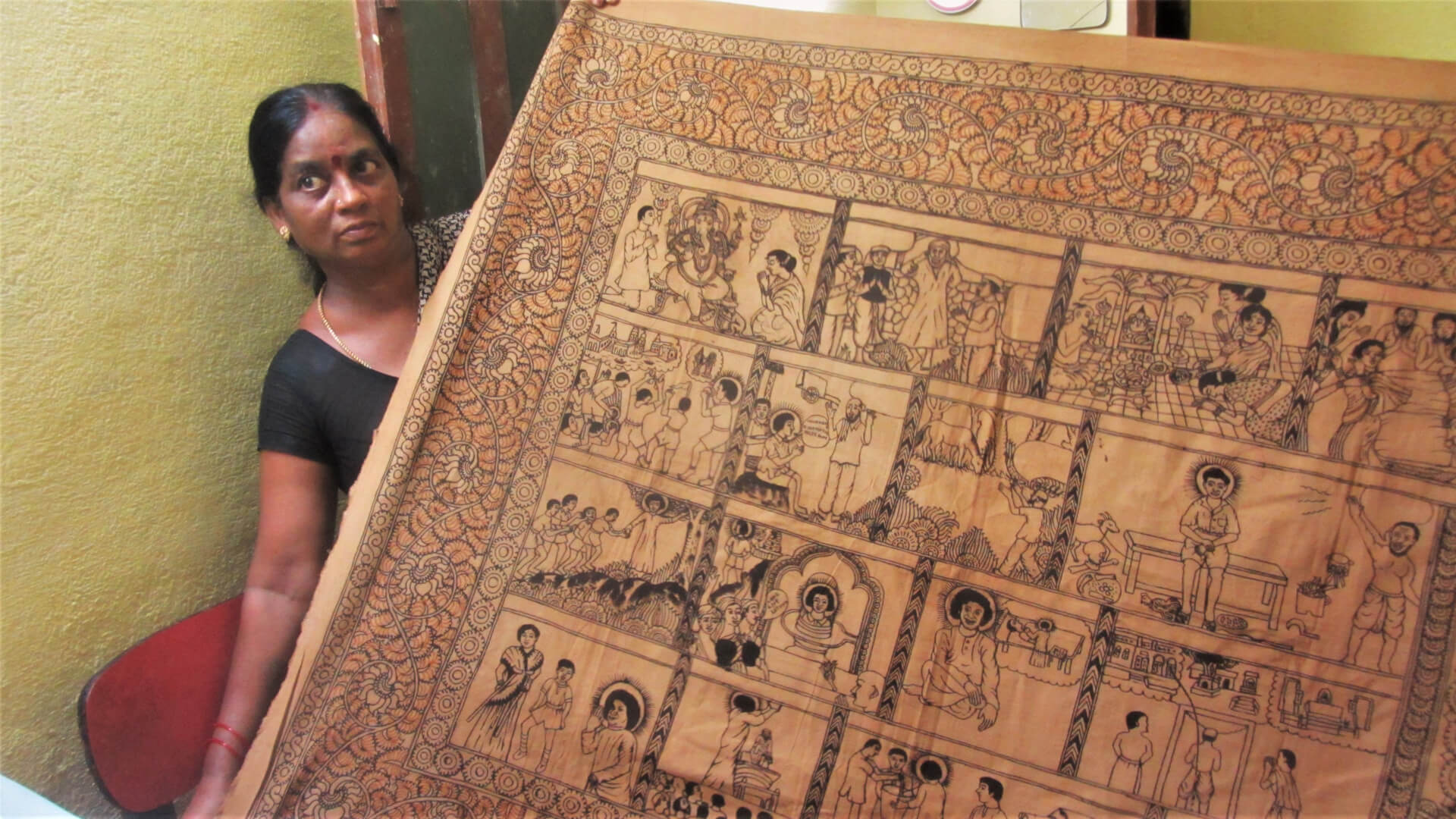

Whereas Das and Kailasham consciously pushed the perimeters of the narrative kalamkari hangings, the late kalamkari maker A. Munikrishnan experimented with compartmentalisation of the Srikalahasti-style temple hangings and infused compositional elements of popular comic strips. He drew two nearly identical narrative hangings on Shirdi Sai Baba and Sathya Sai Baba—two highly revered religious gurus of the Deccan for an unknown patron in the late 1970s/early 1980s. Trained under the legendary kalamkari maker J. Lakshmaiah, Munikrishnan has produced large-scale temple hangings since the 1960s. Most of his works were characterised by densely packed narrative scenes with a high degree of ornamentation except for the twin Sai Baba hangings. In the Shirdi Sai Baba piece, mordant was applied in parts and developed in madder; some of the speech bubbles drawn with black dye do not hold any script. In a traditional setting, usually, all drawings in black are done prior to applying mordant. Only after uniformly applying mordant to the required sections, the textiles are developed in natural dyes. This hanging shows clear traces of partial hanging which is unusual much like its theme. As Munikrishnan turned increasingly forgetful since the 1990s and more after the death of his wife, A. Dhanalakshmi, the riddles about the Sai Baba hanging remains unanswered. The hanging embodies the ambiguity of why a devoted kalamkari temple hanging maker and teacher opted for such compositional experimentation.

Gallery 1

Cloth at Crossroads

The life of a myrobalan-dyed untailored fabric bears many similarities to that of the kalamkari maker: at the crossroads of utility and artistic endeavour; replete with possibilities yet largely undervalued. Artisans’ intrinsic ability to negotiate their responsibility and interests enables them to transcend the fraught disciplinary boundary between art and fashion propagated by colonial education. As many facets of the artisanal histories were systematically suppressed leaving limited opportunities to retrieve them, artisanal skill to accomplish different goals with similar dedication hints at the continuation of perhaps a pre-colonial practice. The sensibility, responsibility and undying spirit of experimentation of the textile makers contributed to the visual and technological complexity of the chintz. Narratives of the cloth and narratives depicted onto them are brought closer through the artisanal interventions. For that, chintz textiles are simultaneously objects of fashion as well as art; they are produced primarily for utilitarian purposes but they have continually provoked thoughts, questions, amazement and confusion for whoever has encountered them.

References

References

Barnes, Ruth. 2020. “Indian Textiles for the Lands below the Winds: The Trade with Maritime Southeast Asia.” In Cloth That Changed the World: The Art and Fashion of Indian Chintz, edited by Sarah Fee, 72-81. Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, distributed by Yale University Press.

Barthes, Roland. 1990. The Fashion System, translated by Matthew Ward and Richard Howard. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Crill, Rosemary. 2020. “A Revolution in the Bedroom: Chintz Interiors in the West.” In Cloth That Changed the World, edited by Sarah Fee, 106-35. Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, distributed by Yale University Press.

Edwards, Eiluned. 2020. “Textiles in Bloom: Block-print Revival and Contemporary Fashion in Northwestern India.” In Cloth That Changed the World, edited by Sarah Fee, 241-50. Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, distributed by Yale University Press.

Palmer, Alexandra. 2020. “Sarah Clothes: Bringing India to Canada, 1975-1996.” In Cloth That Changed the World, edited by Sarah Fee, 253-63. Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, distributed by Yale University Press.

Patel, Divia. 2020. “Fashion: A Future for Printed and Painted Textiles?.” In Cloth That Changed the World, edited by Sarah Fee, 264-76. Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, distributed by Yale University Press.

Interviews

Das, Ajit Kumar. Interview by Rajarshi Sengupta. Personal interview. Kolkata, 2019, 2021.

Kailasham, M.Interview by Rajarshi Sengupta. Personal interview. Hyderabad, 2019.

Rajarshi Sengupta

Rajarshi Sengupta is a practitioner and art historian presently teaching at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology.