The Year of the Dragon

Two new paintings by Wu Lan-Chiann mark the start of the Lunar New Year, showcasing the popularity of the dragon motif in Chinese art and culture.

Published

Category

The Lunar New Year

The Lunar New Year is a significant annual festival in traditional Chinese society. Marking the first day of a year in the lunar calendar based on the monthly phases of the moon, the holiday is widely celebrated among Chinese communities worldwide, as well as in various Asian countries, including Korea, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia. This festive occasion is marked by family reunions, joyous feasts, and meaningful rituals aimed at bringing luck and prosperity for the year to come. The Lunar New Year of 2024 marks the beginning of the Year of the Dragon, the fifth in the 12-year cycle of Chinese zodiac animals.

The dragon holds a revered status as one of the most popular mythical creatures in Chinese culture. The ancient Chinese imagined dragons as supernatural beings, with the power to bring thunder and rain to nourish the earth. Revered for their sublime status, wisdom, and benevolence, dragons also became the symbol of royalty in imperial China. Images of five-clawed dragons adorned a myriad of royal possessions, ranging from ceremonial garments, vessels, and daily utensils to furniture, architecture, and burial artifacts.

Enduring symbols of power, luck, and prosperity

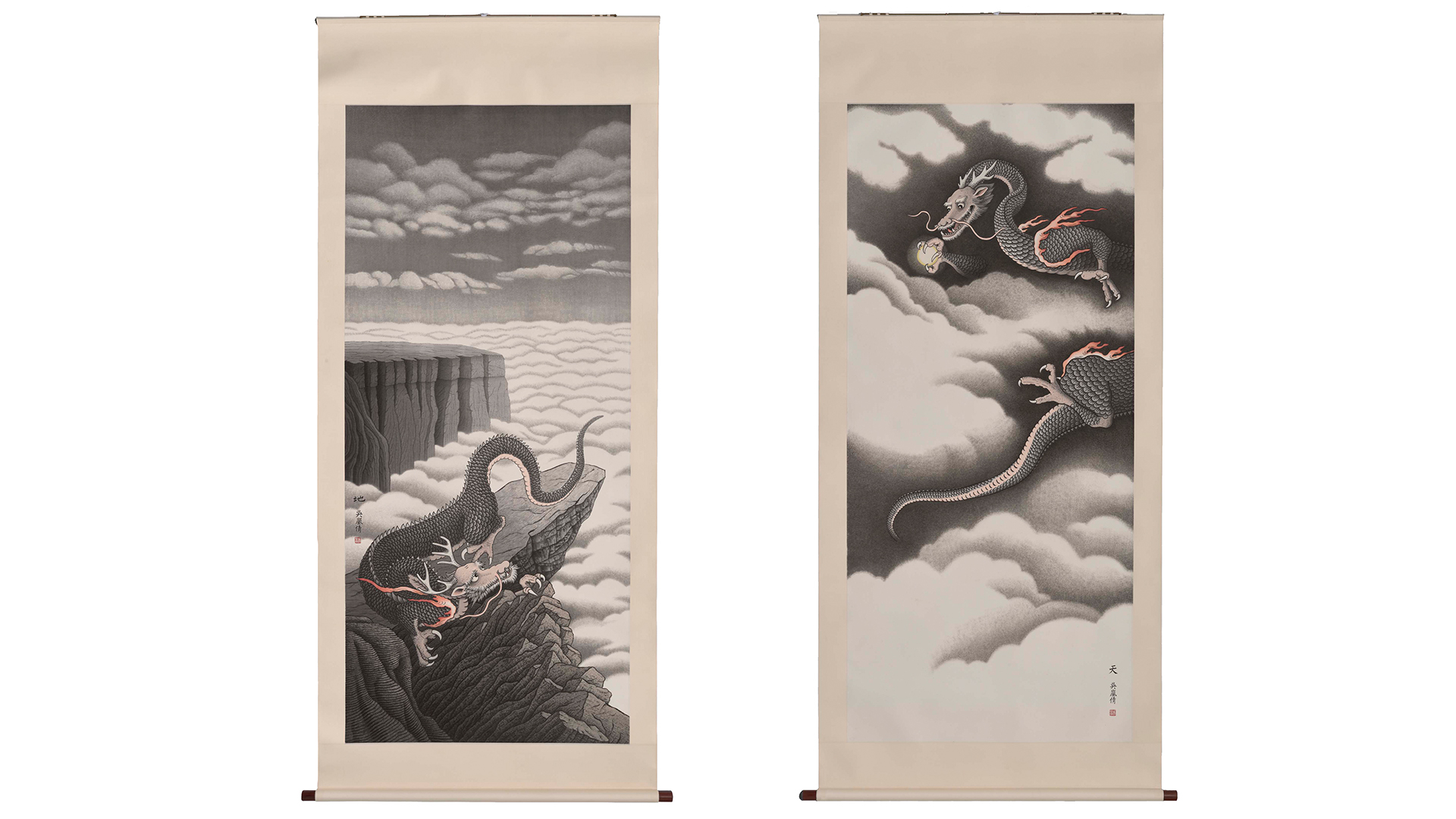

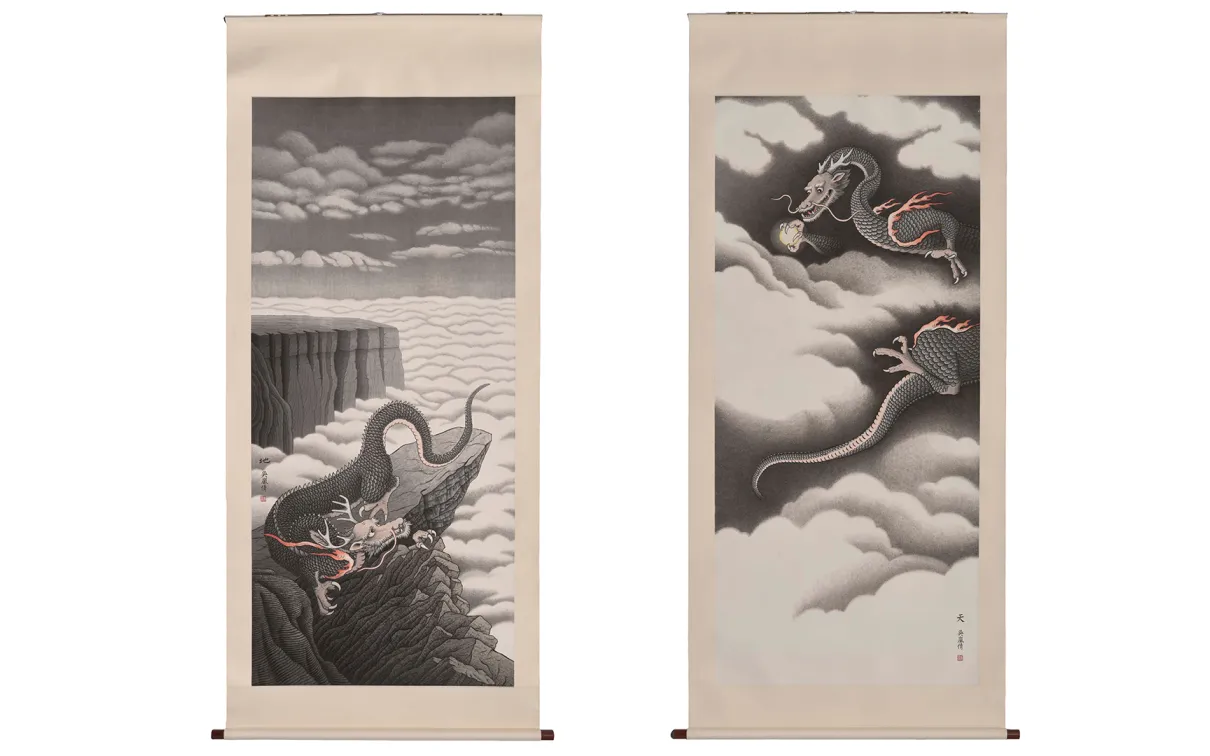

As enduring symbols of power, luck, and prosperity, the dragon motif remains extremely popular in Chinese art and decor. The red lacquer box from the Qianlong period (1736–1795), Qing dynasty, currently showcased in ROM’s Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Gallery of China, is a nice example of a vessel decorated exquisitely with the motif of dragons. The box lid features an energetic serpentine dragon rising from rolling waves, with four profile-view dragons chasing flaming pearls and circling the central dragon. This remarkable box is one of the inspirations for contemporary artist Wu Lan-Chiann’s 吳嵐倩 (b. 1972) creation of a pair of dragon paintings titled Heaven and Earth, currently on view in the ROM’s China gallery.

Intriguing Contrasts

The two dragons reveal intriguing contrasts: one appears energetic, while the other emanates calm. One is younger, the other older (with longer mustaches). As one raises its claws, the other seemingly lowers its body in response, Wu captures a snapshot of an uncertain moment between their alert gazes, leaving room in the viewer’s imagination about the nature of the dragons’ interaction.

“The interaction between the dragons echoes the tension of our world. Life is full of opposites. Good and evil. War and peace. Hesitation and action. Love and hate. These exist in every society, old and new. Contradictions define life itself—with life comes death,” says Wu. Employing traditional ink brush painting as her medium, she explores universal themes that transcend cultural, temporal, and special boundaries.

There are specific contemporary circumstances behind Wu’s portrayal of dragons. “The global turmoil caused by the pandemic, wars, mass migration, and extreme weather events, combined with the Chinese zodiac’s Year of the Dragon, are the contexts in which I created Heaven and Earth,” she says. She views her dragons as benevolent guardians who could protect human existence in the space between heaven and earth.

Innovation within the confines of a traditional medium—the Chinese brush ink painting in Wu’s case—is always a complex artistic discourse. Now a California-based painter, Wu originally hails from Taiwan, where she received her BFA with the highest honours from the Chinese Cultural University in Taipei. Her proficiency at Chinese traditional ink painting is exemplified in Hare and Magpies after Cui Bai, dated 1994. The work is a faithful copy of the master painter Cui Bai’s (active ca. 1060–85) Shuanxi tu (Hare and Magpies) in the collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

Directly copying masterpieces

Directly copying masterpieces from the past is a fundamental and traditional approach to learning Chinese ink painting. As a part of her undergraduate study, Wu meticulously copied numerous paintings spanning from the Song dynasty to the late Qing dynasty. Among them, she was deeply drawn to Cui Bai’s Shuanxi tu in its dynamic composition which captures a moment of two magpies calling out to scold a hare below, who ventured too close to their nest. The diagonal compositional scheme of this masterpiece is echoed in Wu’s Heaven and Earth.

Adopting a naturalistic approach, Cui Bai utilized images to evoke a sense of motion and sound—the viewer could almost hear the rustling of leaves in the winds and the sharp calls of the magpies. Wu’s skills in recreating meticulous, yet vivid brushstrokes were already outstanding. The primary distinction between her reproduction and Cui's original lies in colour. Faced with the challenge of a greatly darkened painting due to the passage of time, she had to rely on her imagination to reconstruct the supposed vibrant colours of the original masterpiece.

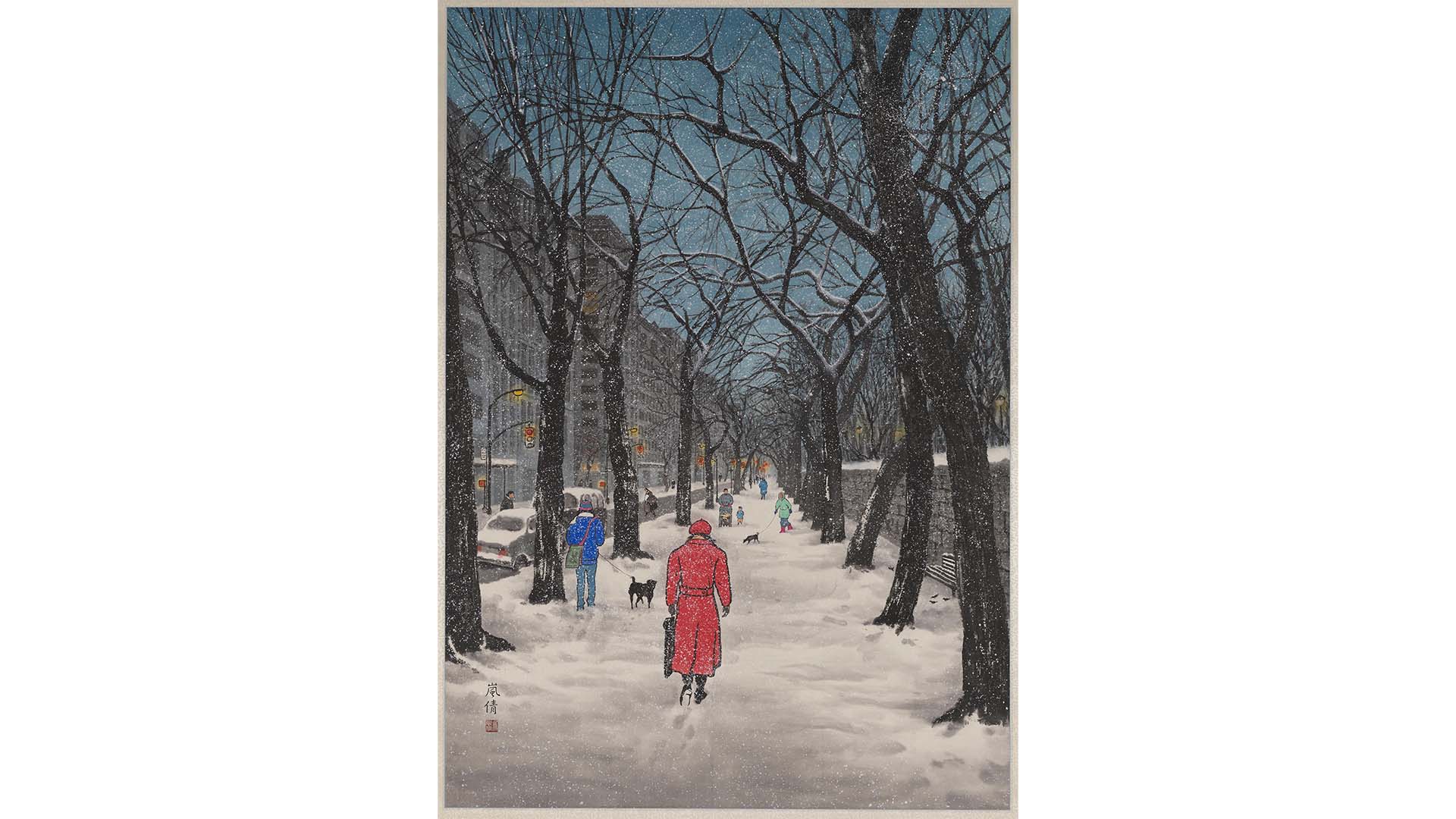

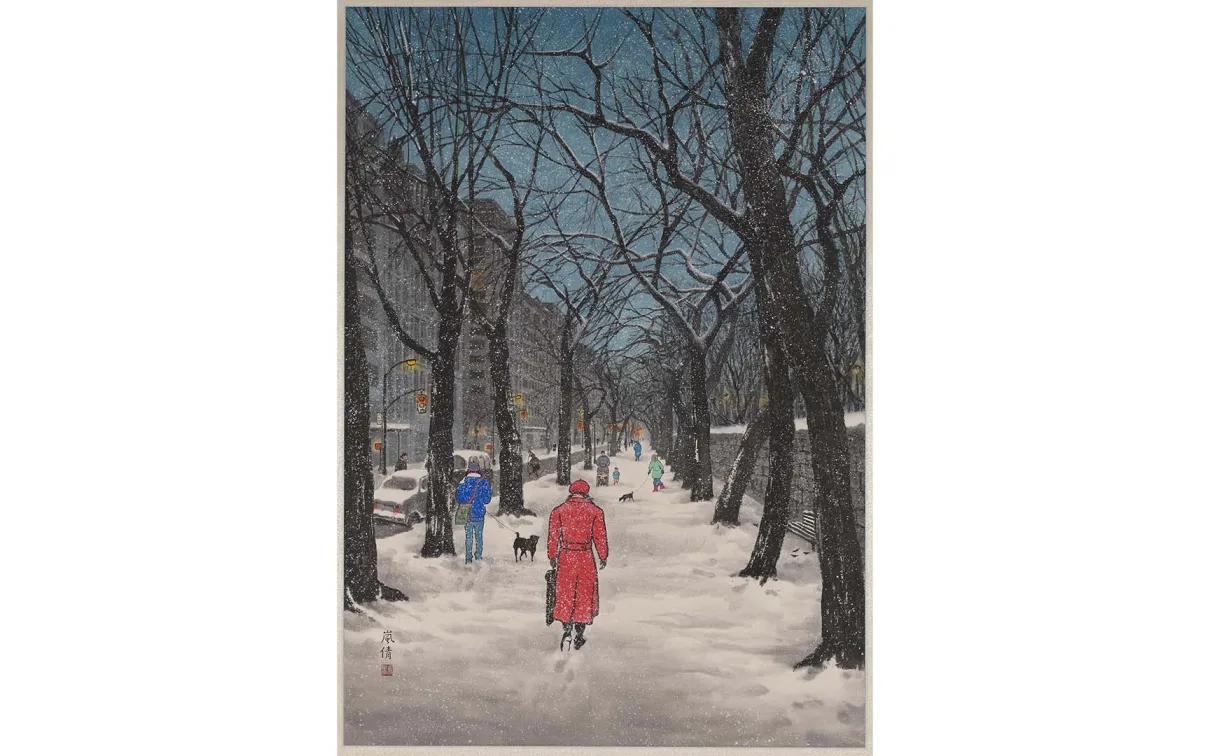

After graduation, Wu decided to pursue her MA in New York University’s Fine Art Department. She has since then immigrated to the United States. Her cross-cultural experience leaves its marks in her art. Wu’s painting Snowflakes Quietly Descending (1999), was created based on the artist’s numerous observations and sketches in situ when she lived in Manhattan, New York City. Illustrating a select view of Fifth Avenue, looking south from the Guggenheim Museum on 89th Street, Snowflakes Quietly Descending captures a quintessential New York cityscape during a snowy night, inviting viewers to walk into the scene. Though painted with a traditional Chinese ink brush, Snowflakes Quietly Descending, deviates from the traditional perception of this art form with its strong colour contrasts, sketch-like quality, and subject matter. The hybridity of eastern and western techniques is visible. While intercultural confrontation certainly plays a role in this work, imbuing local, contemporary life experiences is not a novel concept in Wu’s art. Many of her earlier works from the 1990s feature local Taiwanese scenes—from the night market and streets in old districts, to mountain paths and villages. These paintings reveal a connection to modern Chinese ink painters in Taiwan from the 1980s and 1990s, such as Ho Huai-shuo 何懷碩 (1941–) and Cheng Shan Hsi 鄭善禧 (1932–), whose ink paintings break away from traditional Chinese ink painting subjects and are imbued with a strong local, contemporary flavour of the land and people they live in.

Snowflakes Quietly Descending

In her artist statement for Snowflakes Quietly Descending, Wu addresses the connections her paintings make across time and cultures. “In my work, I delve into universal themes and values, transforming them into imagined realities that link past and present across different cultures,” she says. While the intricate details in the various elements of Heaven and Earth contribute to a realistic effect within an imaginary world, the vibrant visual impact serves as a bridge for the artist to guide her audience beyond the surface toward symbolic meanings. Through these layers, Wu seeks to transcend cultural differences and offer her commentaries on the shared aspects of humanity.

Heaven and Earth by Wu Lan-Chiann are on display at ROM till October 2024.

Wen-chien Cheng

Wen-chien Cheng is the Louise Hawley Stone Chair of Chinese Art at ROM.