The Versatile Vampire

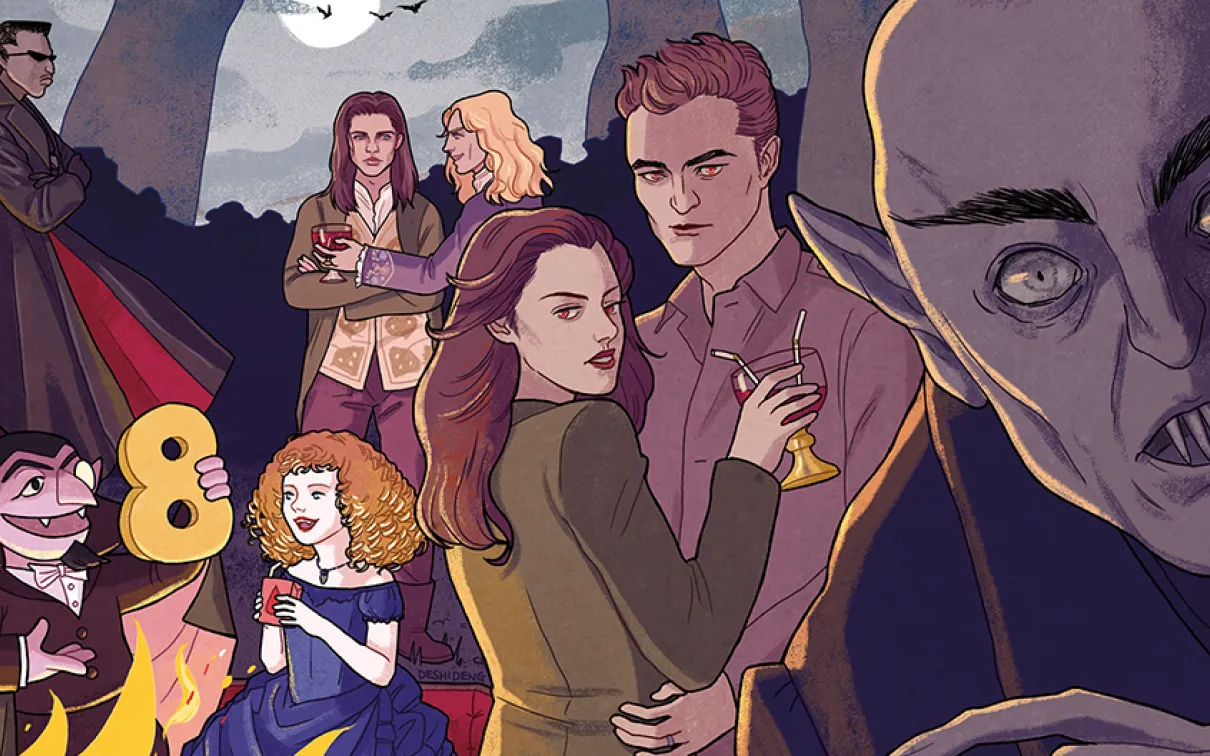

From Count von Count to Edward Cullen, a look at the immortal bloodsucker that has evolved alongside us.

Published

Category

Author

With brooding good looks

With brooding good looks, a hypnotic gaze, and enough charm to raise the dead, vampires have come a long way from their primordial origins. Early iterations of vampires portray nightmarish entities driven by the need to drain the life force from the veins of their prey to replenish their own unnatural strength—as much monster as man.

Today, however, the vampire has become one of the most versatile members of the supernatural. While Frankenstein’s monster, mummies, zombies, werewolves, and even sasquatches have stayed confined within the framework of their original mythology, vampires have morphed from mere bloodfeeding monsters to the suave undead at the top of the food chain. Vampires in popular culture are not only immortal bloodsuckers. Throughout their literary history, they have picked up powers of hypnosis, shape-shifting, Herculean strength, super speed, mind reading, and many others. The vampire has marched from a one-dimensional creature of the night past the brooding Byronic hero to an age where it sits among superheroes and villains. Now, there is Vampirella, a superheroine battling intergalactic and supernatural forces on Earth; Blade, a part-vampire vampire hunter; Dracula and his coven as frequent antagonists to the X-Men; and the universe of Stephenie Meyer’s young adult Twilight novels, in which certain vampires develop unique powers upon “turning.” Our changing beliefs, politics, and ethoses over generations have influenced the characteristics traditionally ascribed to vampire lore. Now, we have vampires that are no longer susceptible to the destructive power of crosses, silver, and garlic, as we witness a shift in storylines away from Judaeo-Christian rules and Victorian social norms.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula

In Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, Dracula, the Professor Van Helsing character suggests that the vampire made a pact with the devil for his immortality through a Transylvanian school of black magic known as the Scholomance. Since then, vampire legends have evolved such that the focus is not on the prize of eternal life, but rather on the cost that comes with the never-ending night.

Stoker’s novel, firmly rooted in Victorian England’s Gothic tradition, is a morality tale with an antagonist who chose not to live by Christian doctrine, essentially avoiding heaven and hell altogether. The name Dracula comes from the Megleno-Romanian word “dracul,” which is derived from the Latin term for dragon but has come to mean “devil.” The mortals who oppose him have to make moral choices to reject and, ultimately, defeat evil.

Like many novels of the era, and horror stories in general, morality underlines the actions and, ultimately, the consequences in Stoker’s story. The solution to the problem is living a virtuous and pious life. But societal values have changed, and the vampire myth with them. No longer is our society so ordered by the philosophy that the choices we make in this world decide whether we achieve eternal life in the next. The shortcut to achieving immortality through unholy magic has lost its poignance, yet that seems to have had little effect on the popularity of vampires.

The distance Stoker’s Count travels from his castle in the Carpathian Mountains to Victorian London pales in comparison to how far the vampire legend has come in popular culture.

Shifting narratives

The narratives have moved past the traditional struggles between good and evil—conflicts of faith and mortality—to explore subjects that search for the humanity within the vampire: inner turmoil, feelings of love, happiness, and grief, and the heavy toll of an immortal existence.

Vampires now are more often cast as antiheroes—or the occasional tragic hero—than as traditional villains. The Swedish novel (and later film adaptation) Let the Right One In probes the isolation and loneliness of a young girl who will forever be an adolescent. By contrast, the character of Claudia in Interview With the Vampire matures to have an adult mind trapped within a child’s body, her story traversing resentment, familial rift, and betrayal.

The vampire has become part of everyday pop culture. There are still lessons imbedded, albeit very different from the Victorian-era ones. Sesame Street’s Count von Count teaches kids math, and a six-year-old vampire demonstrates how to adapt to new surroundings in the Vampirina series. Whereas vampire-human relationships previously signified moral decay and weakness of character, in the Hotel Transylvania animated films we see them reflected as intercultural relationships—a commentary on inherent bias, prejudice, and forgiveness.

The languid bloodfeeding couple in Only Lovers Left Alive capture the magic of an ancient and enduring love in the face of addiction and depression, while a group of New Zealander vampires sharing a flat in What We Do in the Shadowsdispel the conventional hypnotic stare, charming us instead with the banality of their millennial struggles and their human desire to stay relevant in a contemporary society that has largely passed them by.

Vampires have taken many forms

Vampires have taken many forms, acquiring varying strengths and Achilles’ heels along the way. They have been afraid of Christian symbols, and they have been impervious to them. They have been repelled by garlic, and they have been immune to it. In some stories, sunlight can kill them, whereas in others they have developed a resistance. But what continues to define them is their diet of blood, be it human, animal, or synthetic. Perhaps there is something in our fascination with the essence of life coursing through our veins that has made this the vampire’s one consistent characteristic.

The ROM-original exhibition Bloodsuckers: Legends to Leeches traces the various myths and folklore that have emerged out of our fixation on bloodfeeding. There’s Scotland’s baobhan sith, which appears as a beautiful woman who then attacks unsuspecting men, and Ghana’s adzeto, whose bite affects the victim’s business and wealth. Iceland’s draugr rises from the dead if it has unfinished business, while the Dzunukwa out of North American West Coast Indigenous lore devours recalcitrant children.

But Stoker’s Dracula provided the archetype. It codified the vampire for Western audiences, creating a veritable Frankenstein’s monster out of Eastern European history and folklore. It took historical figure Vlad Tepes and merged him with the Romanian strigoi—a type of vampiric entity that could become invisible and transform into animals. Stoker added the connection between vampires and bats, which are now synonymous with the bloodfeeding undead. Yet these immortal exsanguinators from Eastern European folklore could not be more far removed from the New World vampire bats named after them. The distance Stoker’s Count travels from his castle in the Carpathian Mountains to Victorian London pales in comparison to how far the vampire legend has come in popular culture.

As with most folklore, early vampire stories served as cautionary tales, propelling certain beliefs and ideologies. As time passed, and largely due to the influence of Stoker, and later, Hollywood, the creature has been fleshed out from its demonic origins to a being who can be passionate, distraught, and even kind. No longer is the vampire a mere predator or a devil testing his victims’ faith with temptation. The vampire has come to embody traits that echo our emotions, weaknesses, and strengths. And though the vampire’s ability to see its reflection varies by story, it is our likeness reflected back when we look at the modern-day vampire.

Bram Stoker’s Five Rules of Vampirism

Bram Stoker adapted Eastern European lores to make Transylvania the official home of Count Dracula. His novel also introduced certain traits that have since become a vampire’s defining characteristics.

Adapted from Bloodsuckers: Legends to Leeches.

Aversion to Sunlight

This trait first appears in Dracula and may be connected to porphyria—a disease that causes sensitivity to light and blistering as a result of sun exposure.

Weakened by Garlic

Aversion to garlic may have roots in porphyria, symptoms of which include sensitivity to highsulphur foods, like garlic. It appeared as a weakness in Bram Stoker’s Dracula in 1897.

No Reflection in Mirrors

Count Dracula was the first vampire character to appear without a reflection. It is unclear what may have inspired Bram Stoker to include this trait.

A Bite Will Turn a Human Into a Vampire

People believed there were many ways to become a vampire after death, but a bite wasn’t one of them. A vampire’s bite turning a dying person into the undead was introduced in Dracula.

Shape-Shifting Into a Bat

Local tales of shapeshifting did occur in vampire lore, but the first character to turn into a bat was Count Dracula. The name “vampire bat” was first given to an animal in 1810 and may have been an inspiration for Stoker.

Sheeza Sarfraz

Sheeza Sarfraz is Manager of Publishing at ROM.