The ROM Mummies

How ongoing research is pushing the boundaries of Mummy Studies and teaching us about the lives of these ambassadors from the past.

Published

Category

Author

Why do people flock

Why do people flock to exhibits that feature Egyptian mummies? Mummies are people. We can look at some mummies face to face, such as Antjau, while others, like Djedmaatesankh, are cloaked in mystery by her cartonnage, just beyond our gaze. These are the people who made the pots and sculptures and lived in the ancient settlements when they were vital, bustling communities—very different from the ruins we see today. They are ambassadors from the past who reach out to tell us about their lives, and as such, they demand our respect.

The ROM has nine human mummies in its collection, four of whom are on display. These mummies cover the entire span of the Egyptian Empire, from Predynastic times to the Roman period. They were part of the core collection gathered by Charles Trick Currelly, upon which the ROM was founded in 1914.

Gallery 1

The ROM mummies

The ROM mummies have played an important role in the development of mummy studies. Nakht, a teenager from the 20th Dynasty deposits at Deir el-Bahari, was the subject of a scientific autopsy in 1974. A multidisciplinary team employed radiography, histology, and other analytical techniques. Nakht had not been treated like other mummies; he had not been eviscerated and his brain was intact (his parents apparently invested in his coffin rather than his mummification). He had two types of parasites: a tapeworm and schistosomes. The tapeworm would have come from eating contaminated pork, and the schistosomes from wading in infested pools of water.

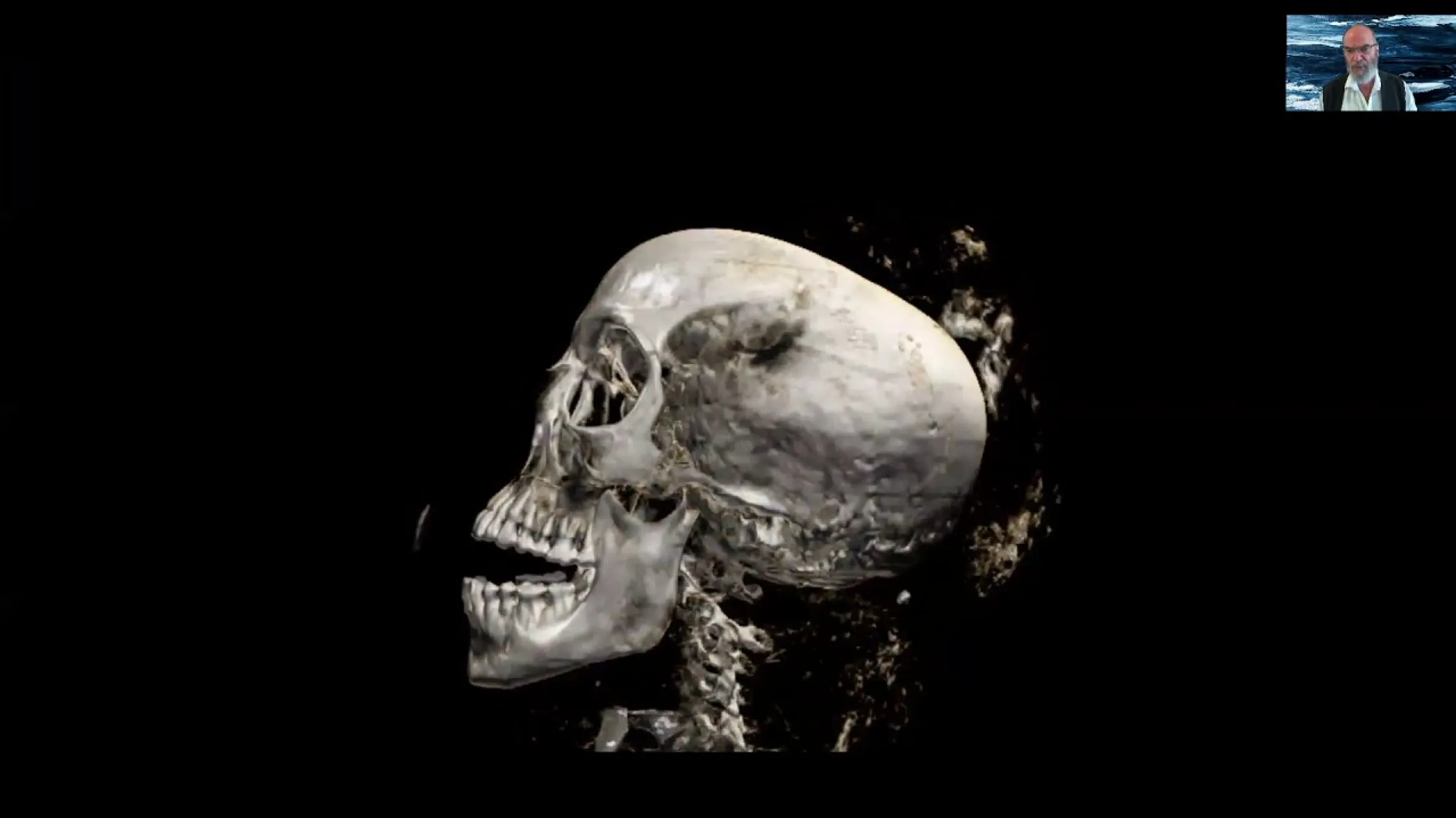

This autopsy yielded abundant information about Nakht’s age, health, and life (and a tunic, the oldest piece of clothing in the ROM’s collection), but it was also destructive. While the process then was state-of-the-art in the 1970s, non-destructive methods of studying mummies have now become the gold standard. Nakht was on the leading edge of that trend; in 1976, his brain was the first “mummy” to be scanned using computed tomography (CT). That feat was rapidly followed by the full body scan of Djedmaatesankh in 1977 (and again in 1994), revealing her spectacular collection of amulets. These scans, done at Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, changed the world of mummy studies.

The research has continued since. In 2007, one adult and two baby mummies were loaned to Western University for CT analysis. The adult, ROM 910.5.2.3 , was believed to be a male, associated with the coffin of a Wab Priest. To our surprise, she was in fact female. Later work associated her with a different coffin, and careful analysis by former ROM Egyptologist Gayle Gibson yielded the name Nefer-Mut, Chantress of Amun. This was no longer an inanimate mummy; she was a woman with a name and a profession—she came alive. The results of the scans have followed her as she has travelled throughout Ontario and China, as an ambassador from Ancient Egypt and the ROM.

Currently, research is focused on the conservation

Currently, research is focused on the conservation, X-ray, and DNA analyses of a mummy known as Djutmose, and on a child mummy, Nesmut, who was also a Chantress. There is a core team of ROM staff and enthusiastic volunteers keen to continue to push the boundaries of mummy studies, focusing on the Museum’s collection, and there will be more to share on this work in the future.

Andrew Nelson

Andrew Nelson is Chair of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Western Ontario.