Portraying a Literary Giant

As the ROM unveils a new portrait of Austin Clarke, artist Neville Clarke shares his thoughts on the creative process.

Published

Category

Author

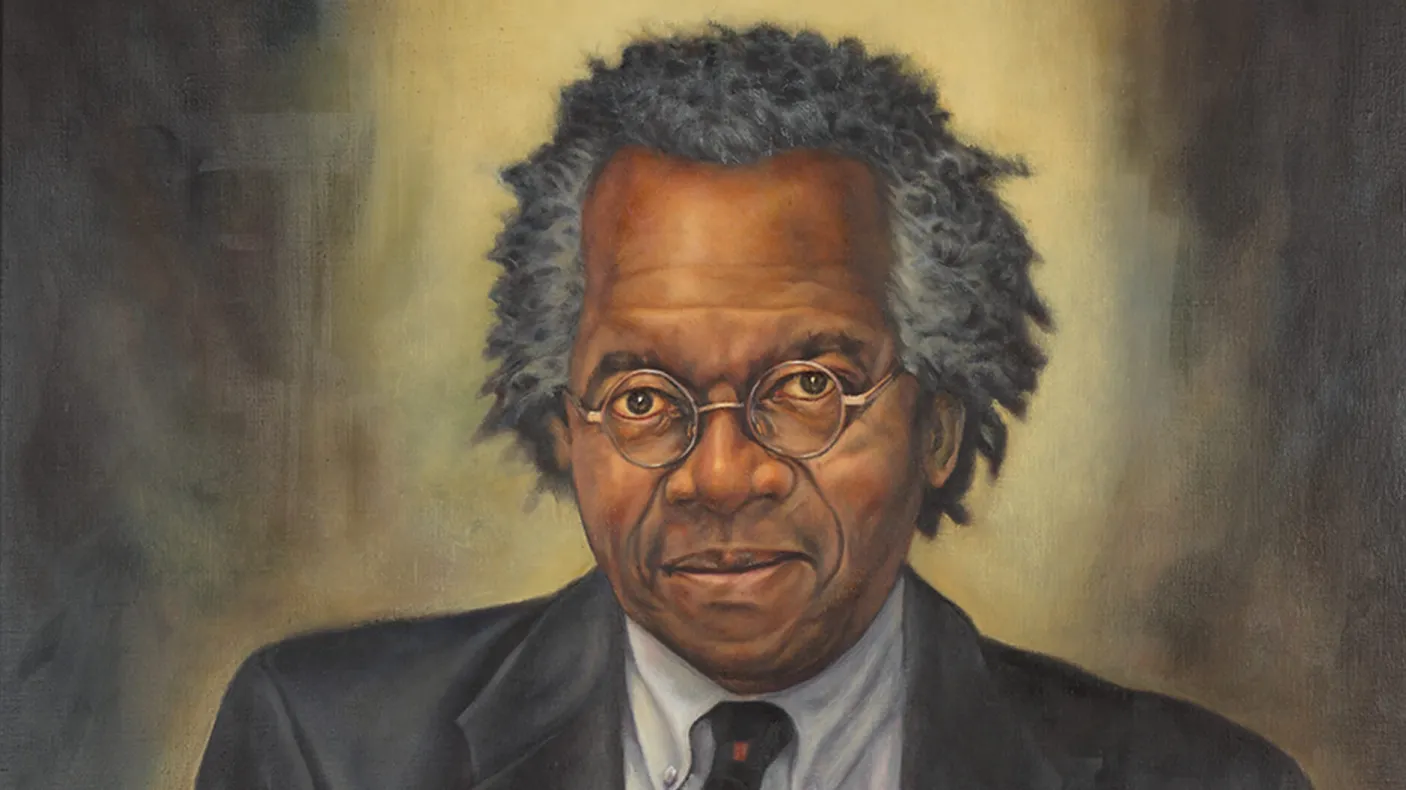

Towards the end of his life

Towards the end of his life, the Canadian portraitist John Wycliffe Lowes Forster (1850–1938) bequeathed a small group of his portraits and a nominal sum of money for the founding of a national portrait gallery of “eminent Canadians.” Today, the ROM is home to the Forster National Portrait Gallery, a discrete collection within the ROM’s holdings. (It is currently not on display.) The collection is composed of subjects Foster considered of cultural import at the time, including authors, performers, educators, and scientists. Recently, the portrait of Austin Clarke—a modern and contemporary cultural figure par excellence—was commissioned from the Forster National Portrait Gallery Fund, and now takes its rightful place within this foundational group as part of the upcoming installation Austin Clarke: Recognizing a Literary Great.

In tune with Forster’s original vision, Austin Clarke (1934–2016) was a renowned novelist, essayist, and poet. Born in Barbados, Clarke immigrated to Canada in 1955, attending Trinity College (University of Toronto). He would eventually go on to run for parliament for the provincial Conservative Party, and work as a journalist and author, focusing primarily on the complexities of life for Caribbean immigrants in Canada.

The installation is part of the Canadian department’s imperative to better reflect in its collection and displays the historical and contemporary diversity of Canadian society.

Artist Neville Clarke (no relation) was commissioned by Arlene Gehmacher, ROM’s Curator of Canadian Art, and Pamela Edmonds, Senior Curator, McMaster Museum of Art to create the portrait. Here, he speaks about his creative process and the significance of diversity in Canada’s cultural institutions.

As a portraitist, you are used to having subjects pose for their portraits. Unfortunately, Austin Clarke passed away in 2016. How did you modify your approach?

NEVILLE CLARKE: Of course, painting and drawing portraits from life is my usual and preferred approach. However, working from photographs and other reference materials can be integral to the creative process. In this case, numerous photos—amateur and professional—were gathered from family members, friends, and public spaces. It is also important to note that physicality is only one aspect of portraiture. I had met Austin in person on several occasions at the Arts & Letters Club of Toronto, as well as at other art-related events, and I had a sense of who he was.

I use light combined with tonal values to structure form and volume, and to evoke mood. The illumination on the face and upper body was a way to shape hard, lost, and soft edges.

It was important for me to understand his complexities

It was important for me to understand his complexities in order to know and appreciate his humanity. To do this, I spoke with his family and consulted writings by and about him. I found he was often described as a generous, compassionate soul who embraced simple pleasures such as cooking and music. But he also had intense political passions, and these didn’t quite accord with the conservative principles of his Anglican belief.

Once you had a critical mass of photographs and other information, how did the concept for the portrait develop?

I would say it unfolded over time. Capturing the essence of the human form can communicate powerful messages and insight into the subject’s psyche. For me, it was imperative that I understand both Clarke’s physiognomy and his inner strength. I made a range of studies in pencil, watercolour, and acrylic paint over a six-month period to familiarize myself with him. I felt these different studies were critical in combing a clear path forward to individualize him, but in a way that also reflected his public persona. The studies allowed for the exploration of tangible attributes—the Order of Canada pin, the Trinity College tie, and his ever-present handkerchief, for example—but also the less obvious yet equally crucial aspects, such as skin tones and spatial relationships between figure and ground, as well as other idiosyncrasies that were signifiers of Clarke’s monumental presence in Canadian culture.

Such as?

Well, for example, in one study—the penultimate one—I had included a visual reference to Lawren Harris in the form of abstracted shapes. They were subtle and, initially, they held the composition together, serving as a nod to iconic Canadian content—effectively equating him with a member of the Group of Seven whose abstractions were inherently spiritual and philosophically elevated. In the end, though, I found the shapes and colours distracting rather than enhancing and I decided that the actual portrait of Clarke could be its own iconic content. Much in the same manner as the monumental, resilient tree trunk Harris featured in his iconic painting North Shore, Lake Superior.

I made a range of studies in pencil, watercolour, and acrylic paint over a six-month period to familiarize myself with Clarke.

Your use of light is also an important component

Your use of light is also an important component of the portrait.

Very much so. Generally speaking, I use light combined with tonal values to structure form and volume, and to evoke mood. The illumination on the face and upper body was a way to shape hard, lost, and soft edges. I worked the light as a descriptive element, deliberately on the nose and mouth: those are distinctive Clarke features on their own, but they assumed an intensified importance in conjunction with the eyes. I’ve signalled that Clarke has a gentle demeanour—the slightly raised shoulder hints at an element of the casual—but make no mistake, his eyes command the viewer to engage with him. And that slight smile is disarmingly knowing. Very no-nonsense.

I also used light as a device to focus attention to a particular area of the painting and subject. In this regard, the light served a dual purpose: it was the background, but it was also a halo set in contrast to the figure in creating spatial depth. More importantly, it became an attribute that I think people across many cultures would recognize as symbolic of virtue. For me, as a Black Canadian, it resonated particularly loudly because it implicitly acknowledges the respect with which Clarke is regarded, as well as his steadfast beliefs in the face of adversity. His sensitivity to the challenges of immigrants trying to determine their identity in a new context spoke volumes, and I think not just to me.

What would you like visitors to consider when they view the portrait?

Clarke is now a feature portrait within Forster National Portrait Gallery, but my understanding of Austin Clarke, and it is my hope that viewers receive this from my portrait of him, is of a complex man—mild-mannered yet passionate; an individual who marched strongly and resolutely to the beat of his own drum. For me, Clarke’s dreadlocks and round glasses became synonymous with the person whose name is now indelibly inscribed in Canada’s pantheon, not just of literary giants but of civil rights activists.

Arlene Gehmacher

Arlene Gehmacher is Curator of Canadian Paintings, Prints & Drawings at the ROM.

Pamela Edmonds is Senior Curator of the McMaster Museum of Art.

Plans are underway to display the portrait in the Sigmund Samuel Gallery of Canada this winter.