Photographing Polar Bears

Award-winning photographer Martin Gregus on his craft, adventures, and how to scare off polar bears.

Published

Categories

In the spring of 2020

In the spring of 2020, as most Canadians holed up at home, hoarding toilet paper and binging bad news, Martin Gregus got a call from a Manitoba tour company. Covid was crushing their business. Was he still interested in travelling to Hudson Bay to photograph polar bears?

For Martin, a burgeoning nature photographer and filmmaker who had spent more than five years working up north before the pandemic hit, the answer was a resounding yes. He would plan and lead the expedition. They would help.

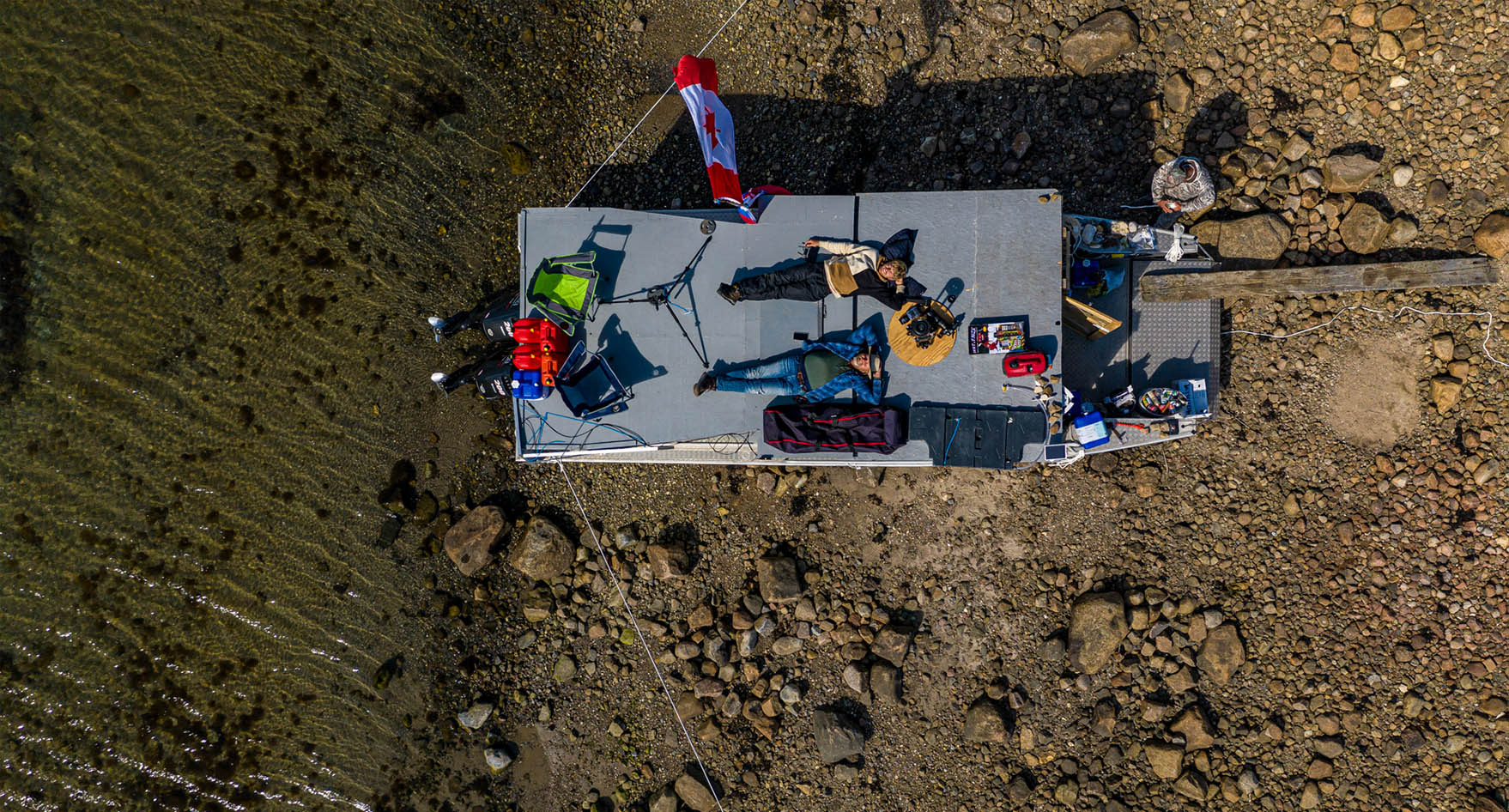

That summer, laden with “five suitcases full of gear and three backpacks, each as heavy as a small child,” he and his crew arrived.

For two weeks, Martin camped near the apex predators, rising at 4 a.m. each morning to watch the sun rise before getting to work. He braved fog and storms. He tinkered with drones. He aligned his circadian rhythms with the bears, waking and napping when they did. And he woke to the sound of a screeching bear alarm, often multiple times a night, forcing him to scramble to the roof for safety.

But, most importantly, he took a lot of pictures. And the results are stunning.

In one photograph, shot by an overhead drone, a mom and her cub nap side-by-side, nestled among a swath of verdant green and grey rocks. In another, a bear swims through choppy waters, its stark white head against a brilliant blue sky.

The series won him the London National History Museum’s Wildlife Photographer of the Year (WPY) Competition “Rising Star Portfolio Award,” spurring coverage in major news outlets around the world.

In November 2021, just after WPY’s big debut at ROM, I connected with Martin to discuss his award-winning series. Sporting a salmon crewneck and a couple weeks’ worth of blonde scruff, Martin opened up about polar bears, his process, and his biggest artistic inspiration: his father.

What’s your favourite photograph in the series

CF: What’s your favourite photograph in the series?

MG: The mother and cub is my favorite in terms of moment. But my favorite photograph is the sea bear, with the wave washing across him when he's in the water. Just ’cause I had that image in my mind for years.

CF: Wow. So, how were you finally able to get that shot?

MG: It took years of planning and finally getting a boat capable of going far enough on the Hudson Bay and big enough that we feel safe in it. Because no one in their right mind is gonna swim with a polar bear. So, just figuring it out over years of going to the Arctic, then eventually coming to a consensus of, “Okay, we're going to build our remote-control boat, put a camera on it, drive it out, and hope a polar bear swims by.”

CF: How do you protect yourself from getting mauled in the field?

MG: Caution and safety were always our number-one priority, so it's that judgment of which bears are safe and which bears aren't. If there was a big male bear that had a lot of scars, or a skinny bear, you wouldn't go out there. But if it's a family of bears or super healthy bears, then you're more willing to see what they're up to.

I would also never go anywhere without my bear guard, who always had a gun on him. And each of us in the team also carried a horn, bear spray, and some rocks.

CF: Rocks?

MG: Honestly, clanging rocks works better than anything else to scare off a polar bear. The last thing you want to do is use the gun. The air horn works okay, the bear spray’s fine.

You can also throw rocks near the bear, and the bear will usually run off—unless it’s a cub. We had one cub getting a little too close, and I threw a rock to scare it off. But instead of startling it, the bear chased the rock back to camp. They’re very much like puppies sometimes.

Gallery 1

Maybe it’s because of all the Coke ads

CF: Maybe it’s because of all the Coke ads, but most people think of polar bears as snowbound animals. You photographed them in summer. Why?

MG: Whether in National Geographic or on TV, we usually see the polar bears in snow. What do these bears do in the summertime? ’Cause usually when we see them in the summertime, they're skinny. They're malnourished.

That’s where the idea for the trip came from. And we were able to see some unique behaviors that you wouldn't see in the winter.

CF: You captured these apex predators at their most intimate and vulnerable: playing, nursing, napping. Why those moments?

MG: If people have a connection with something, they are more prone to protecting it. I wanted these images to convey polar bears as loving families, these animals that are just trying to survive.

They're facing tremendous challenges in their environment due to humans, and if we protect them and just leave them alone, they have the opportunity to flourish.

CF: You’ve been shooting nature since you were eight years old. And not just amateur shots, either—you won the 11-14 age category of WPY in 2010. How has your style and approach evolved over the years?

MG: I look at some of my images that I took when I was younger, and some of them I still like.

My family are immigrants. They never had a lot of money, and these photos were taken on a very small budget. When I first started photography, I was taking pictures with a tiny Sony camera. The two images that got awarded at Wildlife Photographer of the Year were taken with a 6-megapixel Nikon D70, which I inherited from my dad when he bought a better camera.

And that's what I always want to tell people. It doesn't matter what equipment you have, as long as you have the eye and the talent for it.

CF: WPY crowned you a “Rising Star.” Whose work do you turn to for inspiration?

MG: My biggest inspiration is my dad. He has been a photographer for over 40 years and he's the one that got me into it. He's the one that I always turn to for advice, whether it be planning images, building equipment, or even sending emails to people. We work hand in hand. Even for the drone stuff, we plan all the shots together. So, he is the one I always look to and who I strive to be like.

CF: Tell me about your next expedition.

MG: I have a big one coming up to Mexico in February, so we're going for a week or two to document whale migration in Baja. And then I'll probably spend most of my next summer somewhere in the Arctic, whether it be Churchill or potentially even higher up north.

Colin J. Fleming

Colin J. Fleming is Senior Communications Creative Strategist at ROM.