Measure for Measure

New research reveals how differing techniques of weighing a dinosaur yield strikingly similar results.

Published

Category

Author

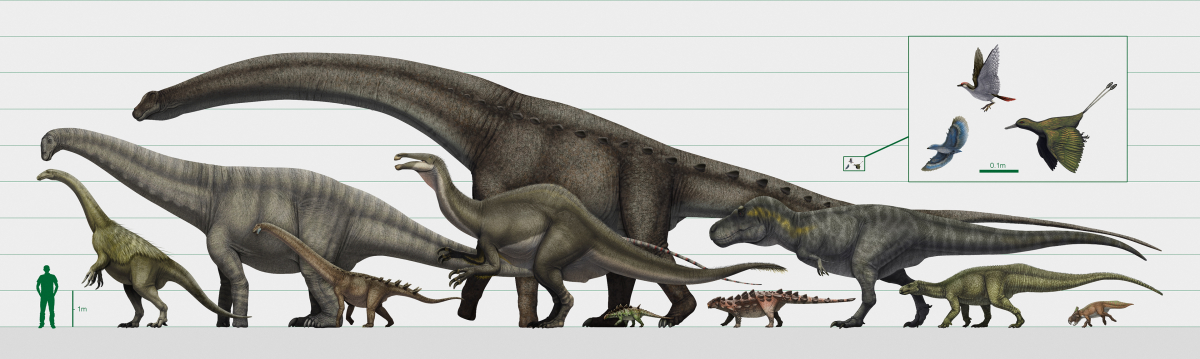

The largest and the smallest

The largest and the smallest: dinosaurs reached an amazing range in size through the Mesozoic Era. Image courtesy of Vitor Silva.

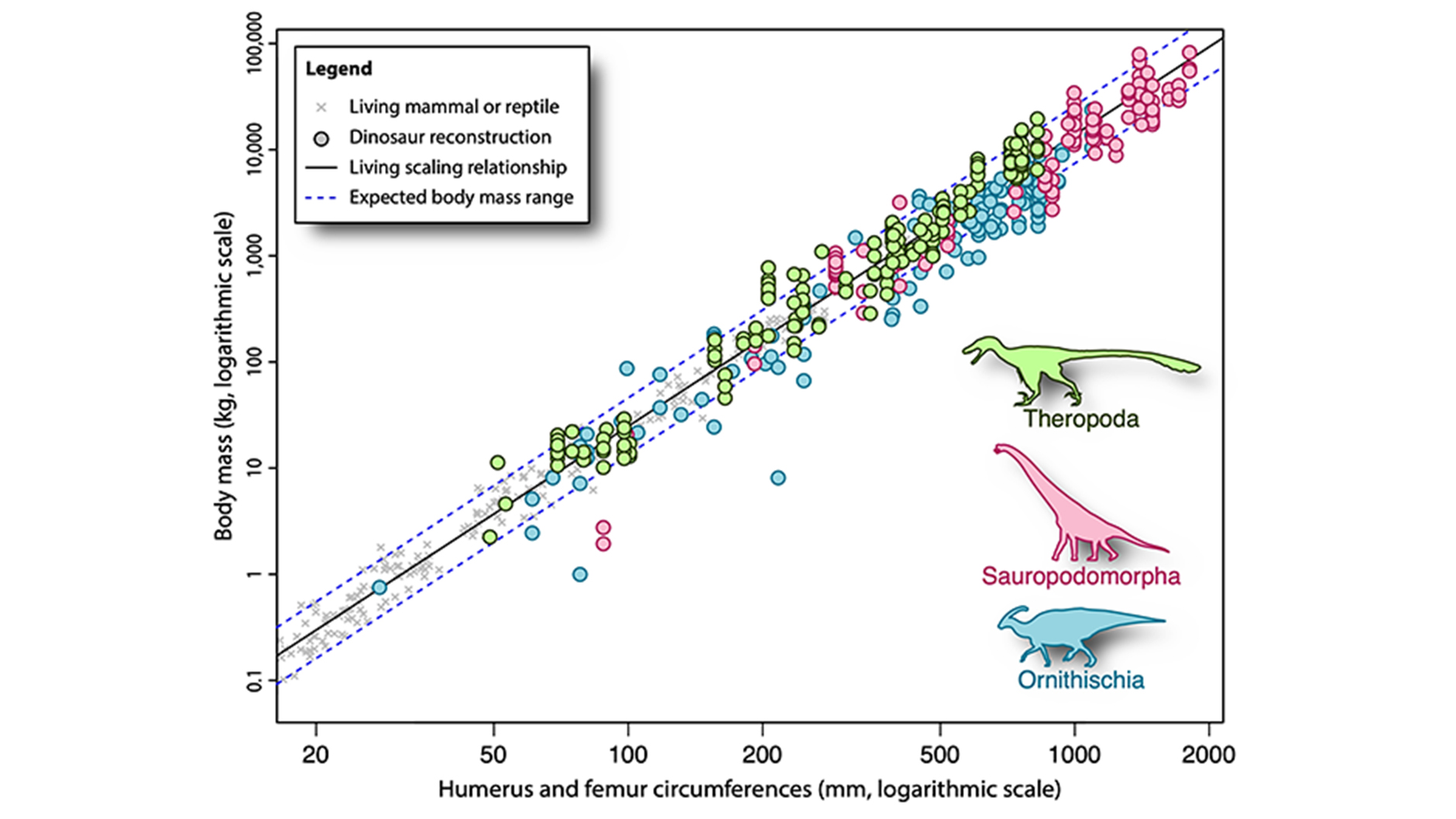

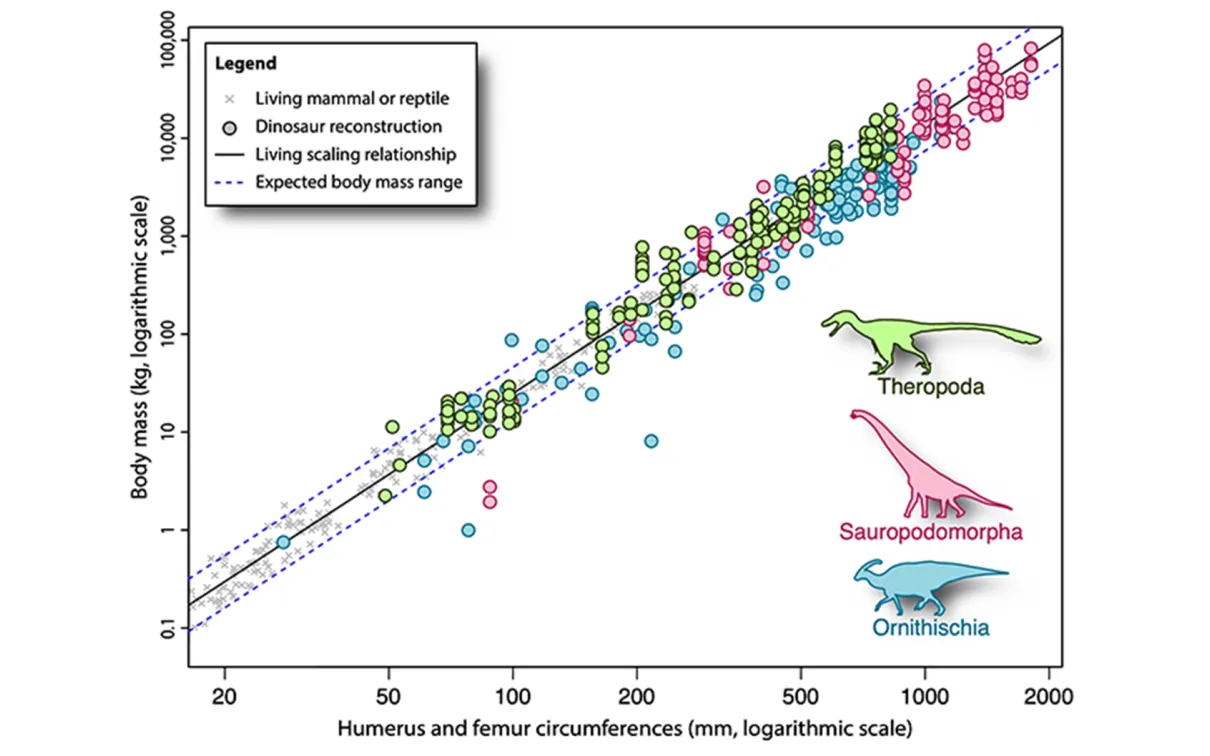

How does one weigh an animal that went extinct millions of years ago? Although a range of different methods to estimating body mass have been tried over the years, it comes down to two fundamental approaches: measuring and scaling bones from living animals to compare with the dinosaur fossils, or calculating the volume of three-dimensional life reconstructions that approximate what the animal may have looked like in real life.

While there has been heated debate over which method is better, a new paper published in the prestigious journal Biological Reviews reveals that while opinion on the preferred method might differ, both techniques yield strikingly similar results.

“The findings should give us some confidence that we are building an accurate picture of these prehistoric animals,” says study leader Nicolás Campione, who did the study as a part of his Ph.D. at the University of Toronto and the ROM. “Body size, in particular body mass, determines almost at all aspects of an animal’s life, including their diet, reproduction, and locomotion. If we know that we have a good estimate of a dinosaur’s body mass, then we have a firm foundation from which to study and understand their life retrospectively.”

The research team of Campione

The research team of Campione and David Evans (Royal Ontario Museum Temerty Chair of Vertebrate Palaeotology) compiled and reviewed an extensive database of dinosaur body mass estimates reaching back to 1905, to assess whether different approaches for calculating dinosaur mass were clarifying or complicating the science. The researchers found that once scaling and reconstruction methods are compared en masse, most estimates agree. Apparent differences are the exception, not the rule.

According to Evans, senior author on the paper and Campione’s Ph.D. supervisor, there will always be uncertainty around understanding long-extinct animals, with weight being a large part of the puzzle. “Our new study suggests we are getting better at weighing dinosaurs, and it paves the way for more realistic dinosaur body mass estimation in the future,” says Evans.

The researchers recommend that future work seeking to estimate the sizes of Mesozoic dinosaurs, and other extinct animals, need to better-integrate the scaling and reconstruction approaches to reap their benefits.

Campione and Evans

Campione and Evans suggest that an adult Tyrannosaurus rex would have weighed approximately seven tonnes, or about as much as bull African bush elephant—an estimate that is consistent across reconstruction and limb bone scaling approaches alike. The research, however, emphasizes the inaccuracy of such single values and the importance of incorporating uncertainty in mass estimates—not least because dinosaurs, like humans, did not come in one neat package. Such uncertainties suggest an average minimum weight of five tonnes and a maximum average weight of 10 tonnes for the “king” of dinosaurs.

“It is only through the combined use of these methods and through understanding their limits and uncertainties that we can begin to reveal the lives of these, and other, long-extinct animals,” says Campione.

Nicolás Campione

Nicolás Campione is a research fellow and lecturer at the University of New England. This study was part of his Ph.D. thesis at the University of Toronto and the Royal Ontario Museum, supervised by David Evans, Temerty Chair of Vertebrate Palaeontology at the ROM.