Great Whales

Published

Category

Author

Great whales are the largest animals living on Earth today

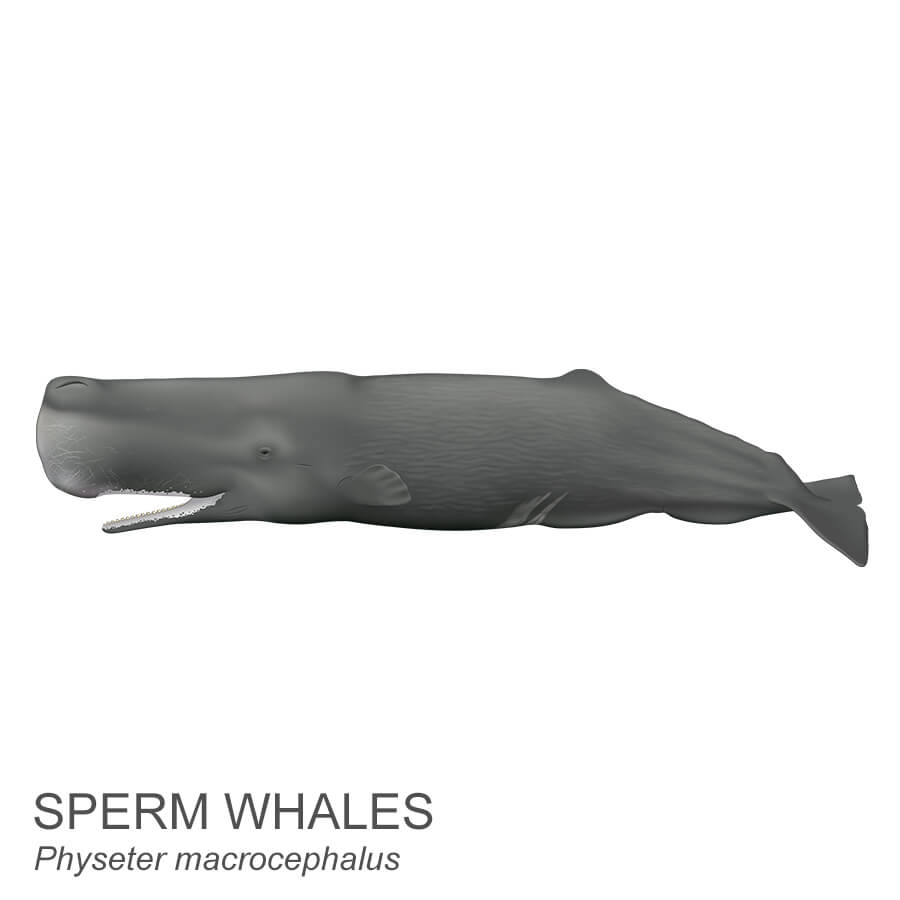

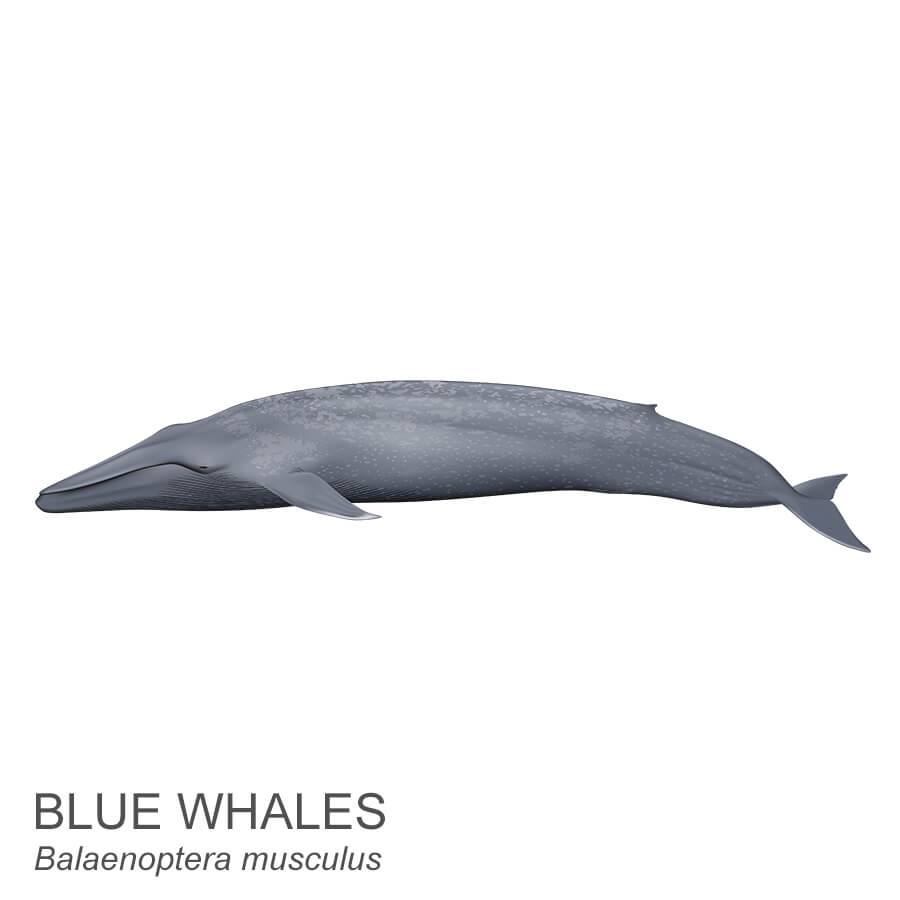

They are typically longer than 10 metres (32 feet) and weigh more than 10 tonnes (22,000 pounds). In addition, great whales are important to ocean ecosystems and have inspired cultures around the world and throughout time. This group includes most of the baleen whales, which feed by filtering prey out of the water, but includes only one toothed whale, the sperm whale. The ROM exhibition Great Whales: Up Close and Personal showcases three great whale species: the blue whale, the North Atlantic right whale, and the sperm whale.

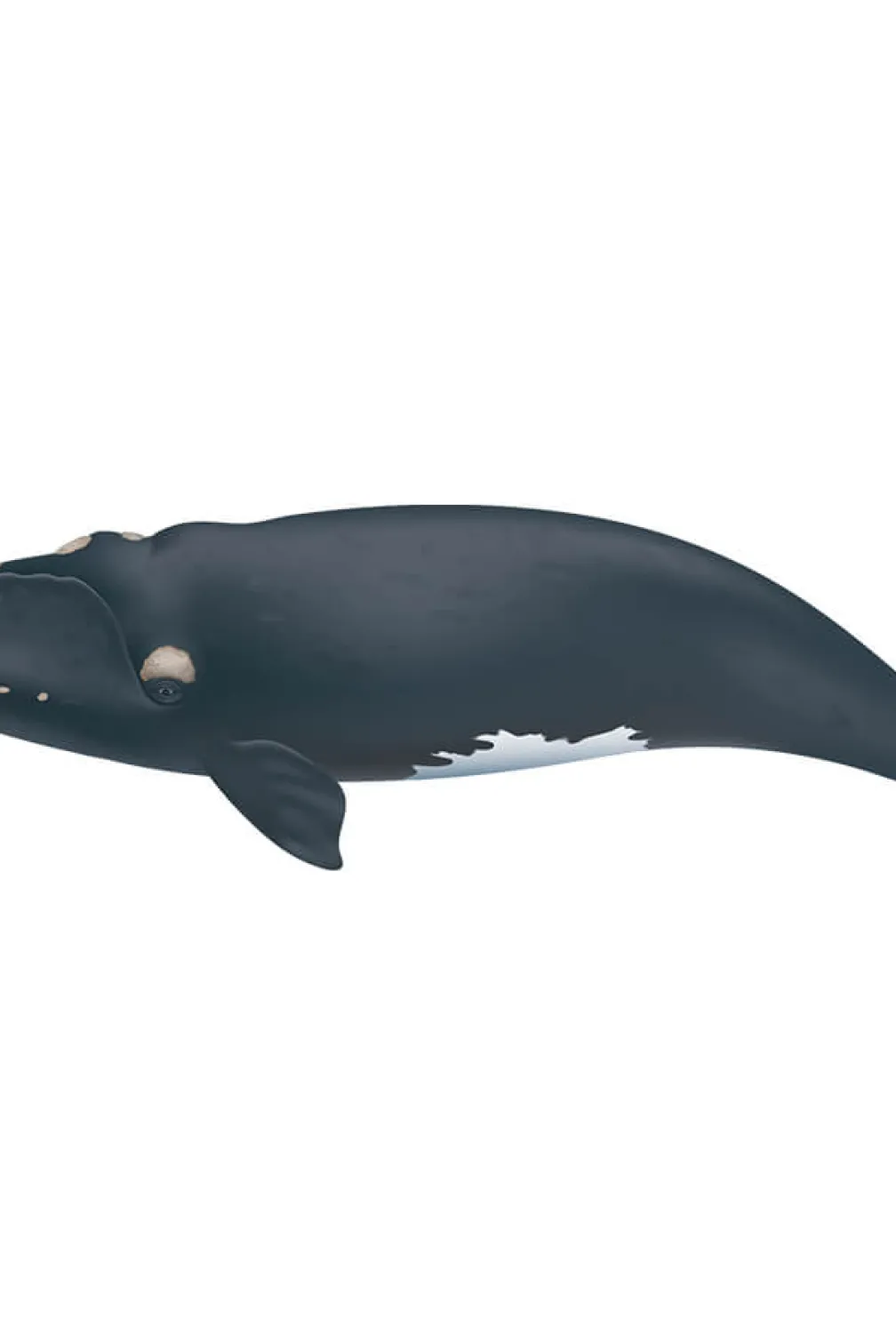

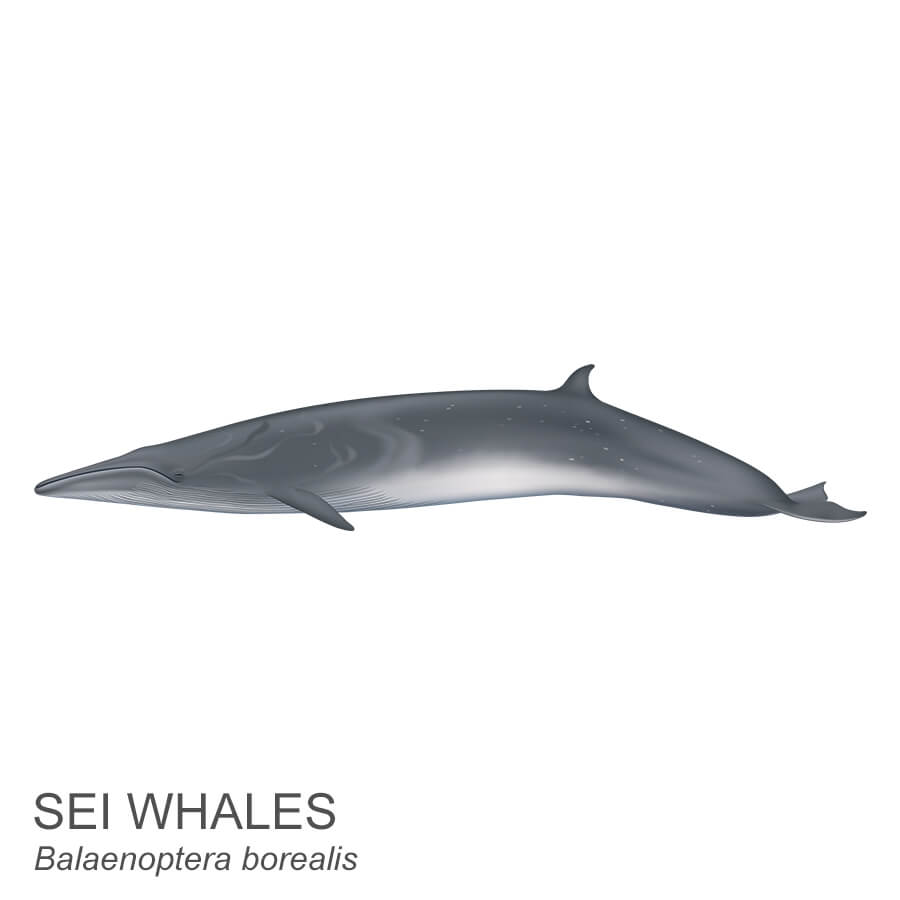

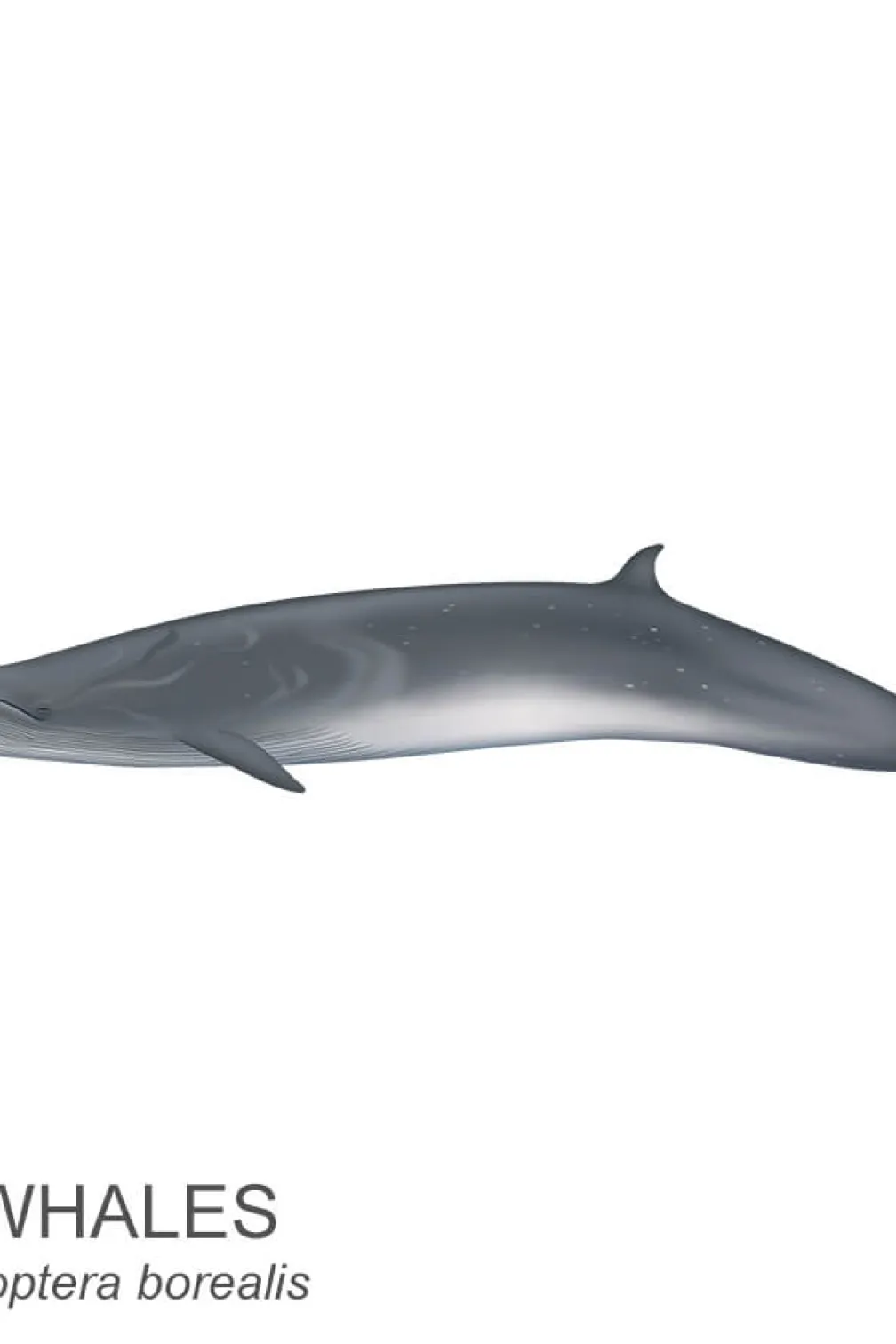

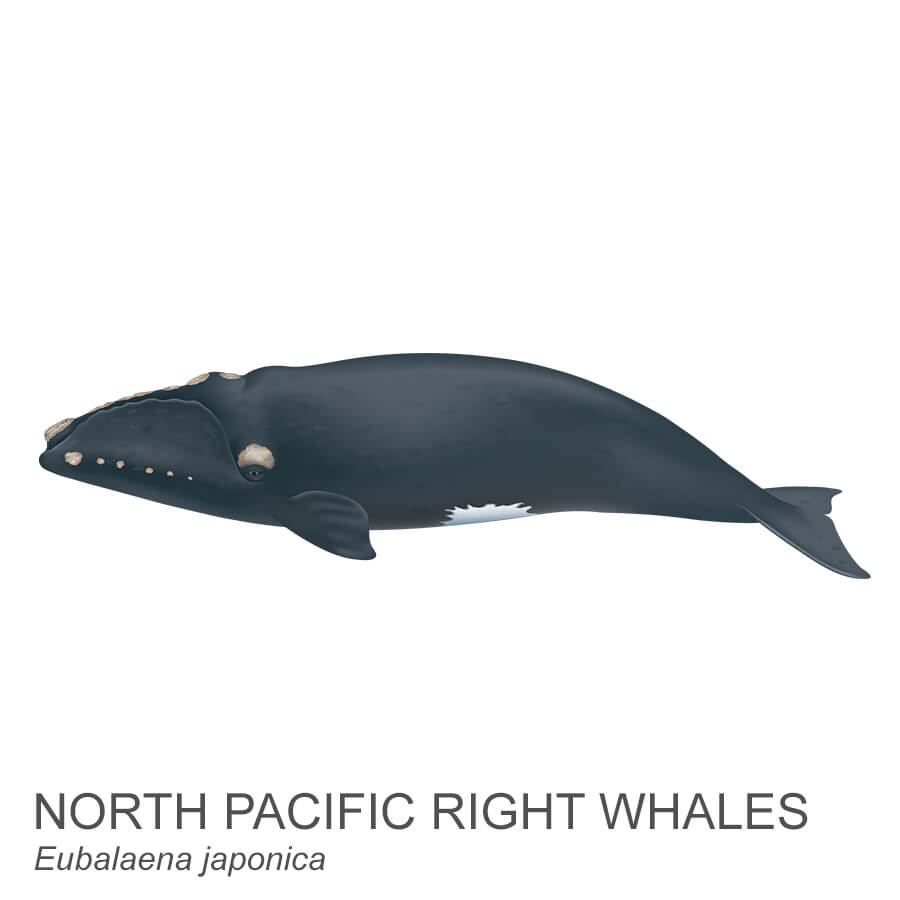

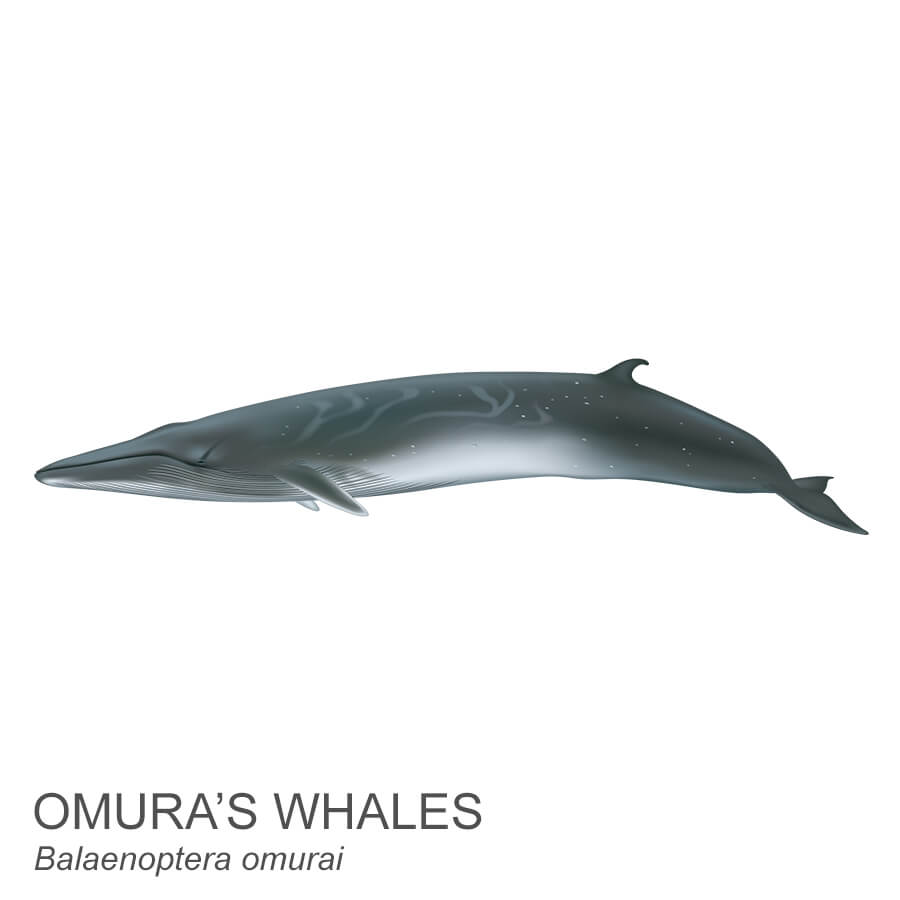

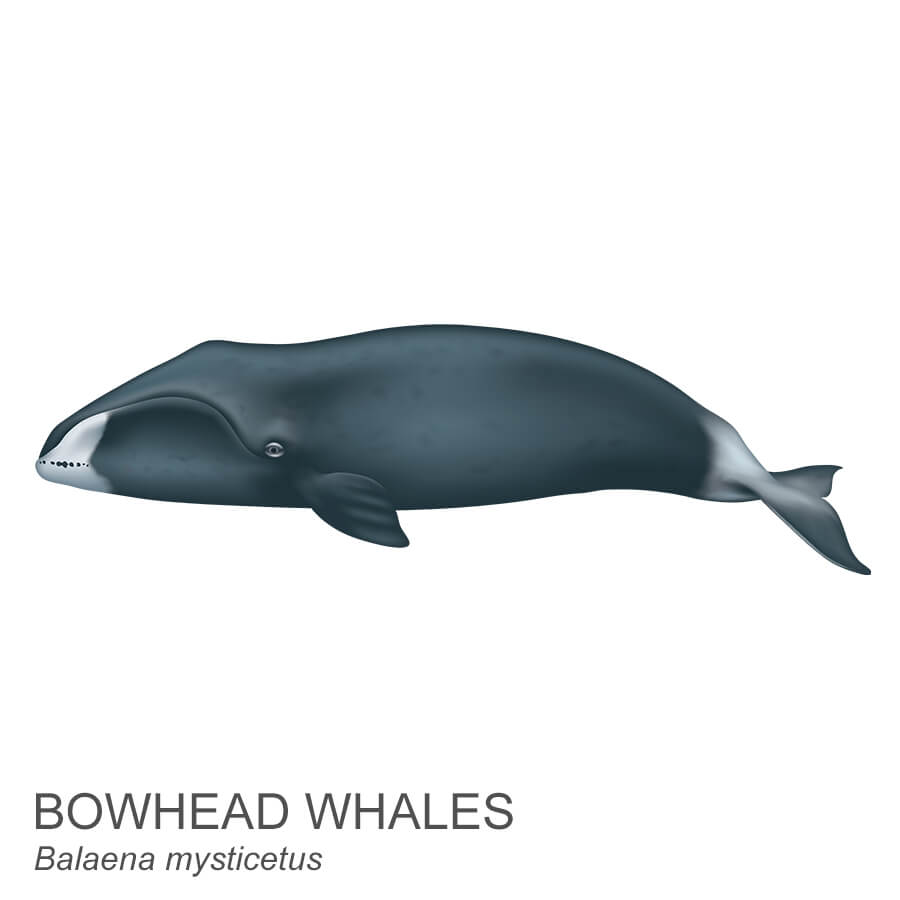

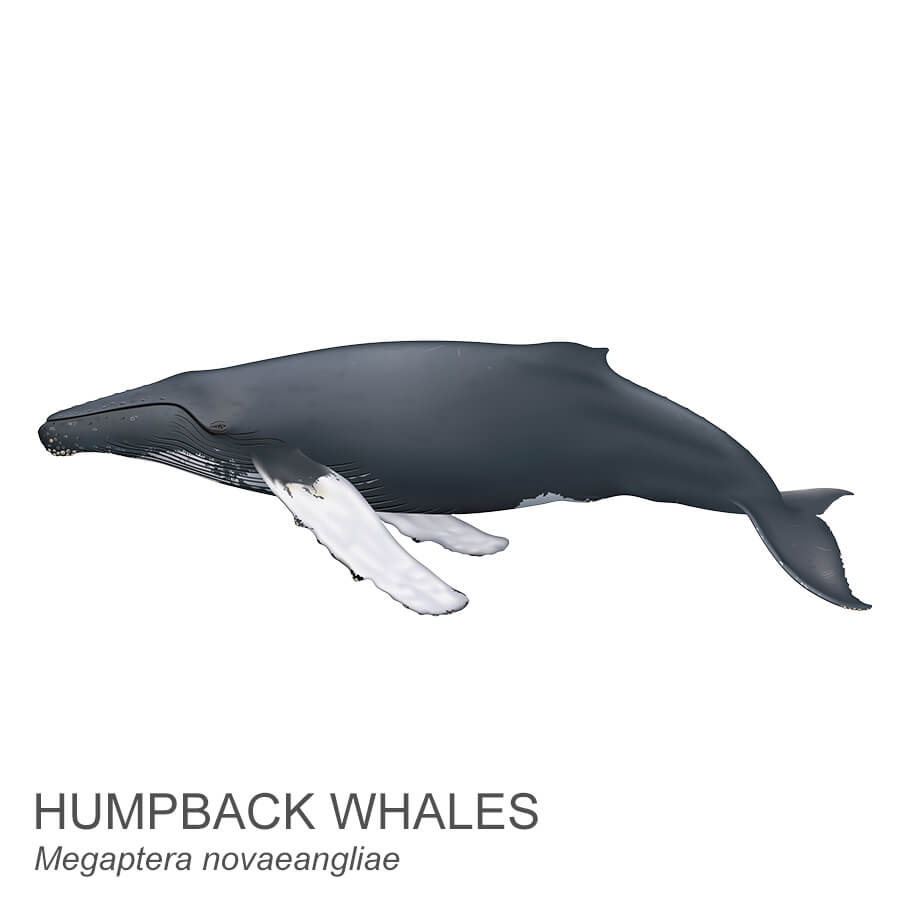

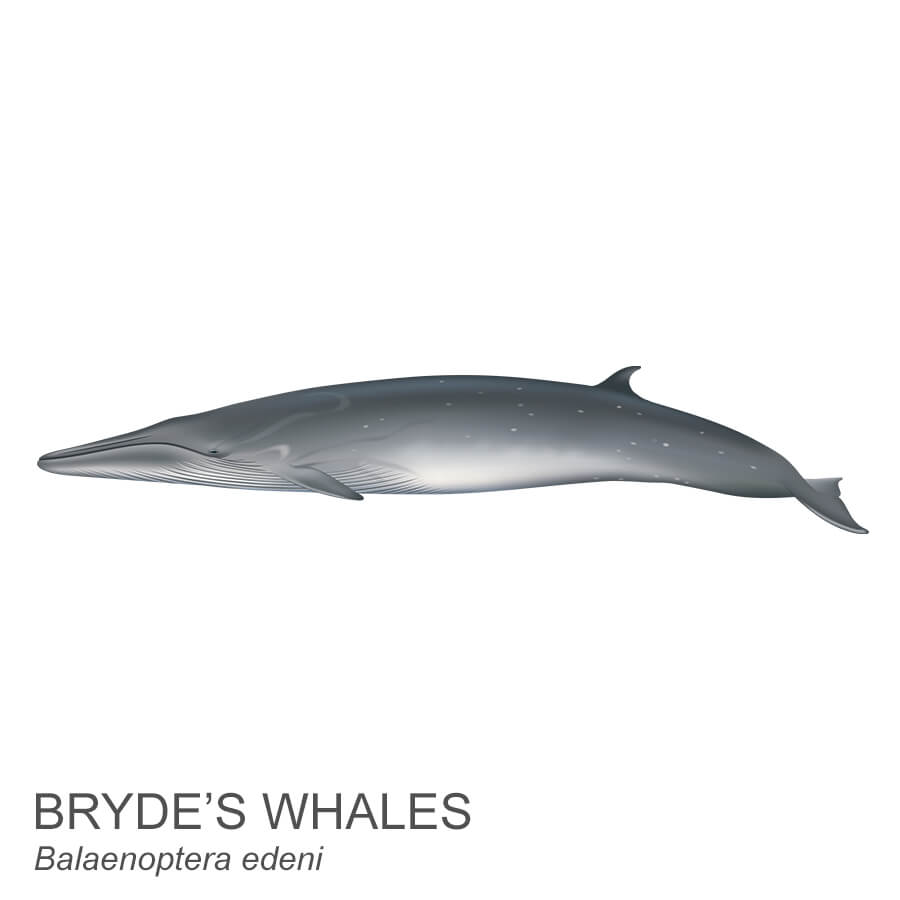

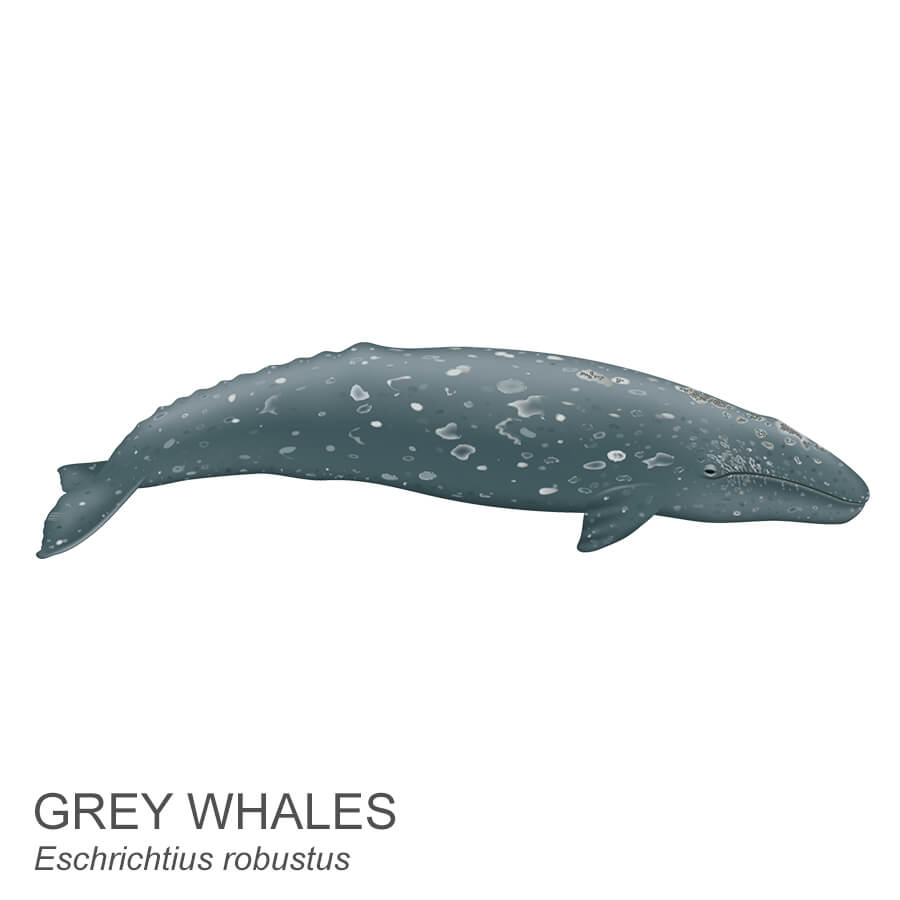

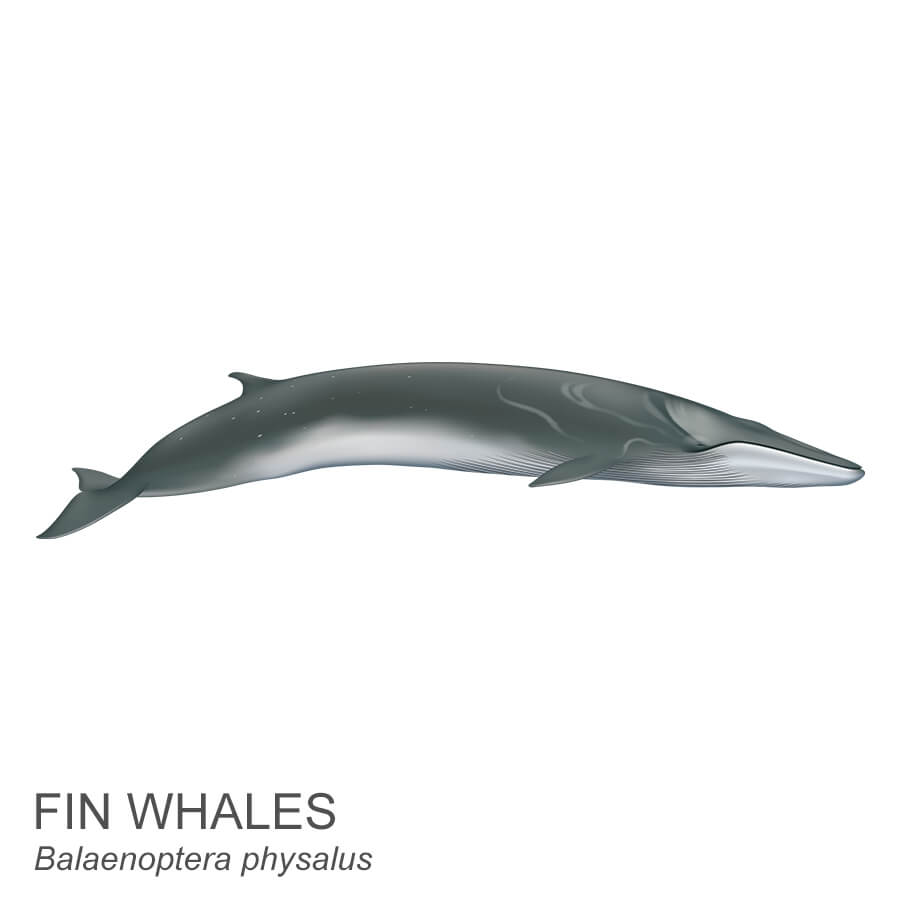

Cetacea is the formal scientific name for whales, and the living whales are divided into Odontoceti (toothed whales) and Mysticeti (baleen whales). Indeed, the largest and most massive whales are mysticetes, which include many familiar species, such as the blue whale—the heaviest animal ever to have lived. But there are several relatively small mysticetes as well. Likewise, there are large toothed whales. The killer whale, or orca, is related to dolphins and is big, but not large enough to be considered a great whale. There are about 90 species of whales in the oceans at this time, of which 12 are considered great whales. In addition to the three species in the ROM’s exhibition, the other nine great whales are the bowhead, southern right, North Pacific right, sei, Bryde’s, Omura’s, fin, grey, and humpback.

Gallery 1

There are about 90 species of whales in the oceans at this time, of which 12 are considered great whales. In addition to the three species in the ROM’s exhibition, the other nine great whales are the bowhead, southern right, North Pacific right, sei, Bryde’s, Omura’s, fin, grey, and humpback.

Gallery 2

Canada’s great whales

Great whales swim in the expansive waters of all the oceans around the globe including the Gulf of St. Lawrence, one of the most productive marine environments in the world. In addition to fresh water from the Great Lakes, it receives the cold Labrador Current from the Arctic and the warm Gulf Stream from the Tropics. This milieu supports a wealth of marine organisms ranging from microscopic plankton to great whales. But the Gulf of St. Lawrence is also a major international shipping corridor and commercial fishing area that is a primary economic driver for Atlantic Canada.

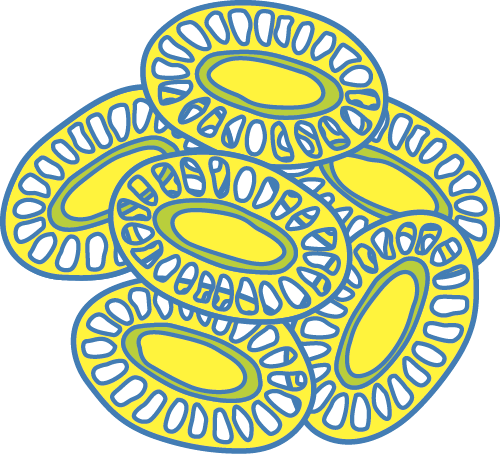

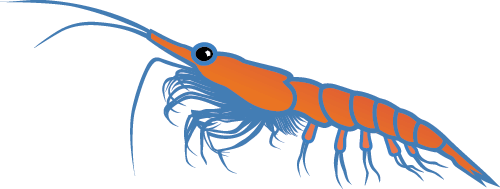

The waters off Canada’s east coast are a prime feeding zone for predators and prey. Blue whales feast on swarms of krill, small shrimp-like crustaceans, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence beginning in the early spring. Until a few years ago, North Atlantic right whales were common in the Bay of Fundy. However, recent climate-driven changes have altered the distribution of copepods, tiny crustaceans that are their main food. This has affected the distribution of North Atlantic right whales. They have begun showing up in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where they were not typically found before, resulting in more ship collisions and entanglements in fishing gear. Sperm whales hunt for squid in the deeper waters farther out in the Northwest Atlantic.

Much remains unknown about where great whales mate and give birth. North Atlantic right whales mate during summer in northern waters, and females migrate south for the winter to give birth off the coast of the southeastern United States. Adult male sperm whales tend to migrate farther toward cooler, higher latitudes during summer than females and younger males. But adult males return to warmer waters to mate. No one has seen a blue whale give birth, and little is known about where it happens. It probably occurs in winter, when whales are in warmer waters nearer to the equator.

The blue whale is the heaviest animal to have ever lived—even heavier than a dinosaur. The blue whale can weigh up to 150 tonnes (330,000 pounds). That’s equal to 2,200 average- sized people weighing 68 kilograms (150 pounds). The ROM’s blue whale weighed about 90 tonnes (200,000 pounds), equivalent to 15 African savanna elephants.

But the tallest animal ever was a giant sauropod that roamed North America about 110 million years ago called Sauroposeidon, which measured 18 metres (59 feet) high. Blue whales are about 5 metres (16 feet) from belly to blowhole. Blue whales can reach about 33 metres (108 feet) in length, with females usually longer than males.

How did great whales get so big?

Whales have been able to reach such great sizes partly because they are adapted to life in the sea and live entirely in water, which supports their great mass and reduces the effects of gravity. Land animals can be only as heavy as their legs can support, and legs can get only so big and still be functional. Whales are buoyed in the ocean, and their size is not as constrained as that of terrestrial animals.

The large size is also attributable to the fact that heat radiates much more rapidly in water than in air. As bodies increase in size, volume increases more quickly than surface area, which means relatively less heat is lost. Whales also have a layer of insulation called blubber, another adaptation that helps them stay warm in cold waters.

The size of most baleen whales requires additional explanation. Lengths over 10 metres may have been achieved some 15 million years ago, and larger-bodied species became more common about 4.5 million years ago. The size increase was driven also by changes in oceanic conditions associated with the repeated advances and recessions during the more recent Ice Ages. These fluctuations in the marine environment changed ocean currents and led to patchy but highly productive feeding opportunities for baleen whales, which eat plankton and other small organisms such as krill, which occur in large swarms.

Eating Habits

Baleen whales can take in a huge amount of food in a single gulp. Some, like right and bowhead whales, swim steadily through a swarm of tiny prey.

Toothed Whales

Toothed whales eat a variety of fish, octopus, cuttlefish, and squid—sperm whales, the largest of the group, even feed on giant squid. Sperm whales use their teeth to grasp large prey, instead of cutting or chewing their meal with sharp teeth.

Blue whales lunge forcefully through a prey swarm to get their fill. They eat about 70 mouthfuls of krill a day! Each gulp can hold about 60 kg (132 lbs.).

Whales at risk

Great whales have been hunted for centuries, first sustainably for food and survival. But as the demand for blubber and baleen increased, so did the whaling. By the end of industrial whaling in the 1980s, the global populations of the largest whales had been reduced by over 95 percent. We have long exploited these giants for commercial and industrial gain. Now, it is up to us to help save them from extinction.

Some of the richest feeding grounds for great whales are found in or near the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Six species are often seen in this extraordinary area, including blue, sperm, and North Atlantic right whales. Today, many whale species are threatened or endangered. In the Northwest Atlantic, whales must avoid ship traffic, escape from fishing lines that entangle them, and overcome challenges caused by human-induced climate change. Our human activity has caused whales great harm, and it is now our responsibility to fix the mistakes and help the whales. Whales can recover if given a chance.

We have long exploited these giants for commercial and industrial gain. Now, it is up to us to help save them from extinction.

There are approximately 360,000 sperm whales left worldwide

There are approximately 360,000 sperm whales left worldwide, a reduction of an estimated 65 percent since before whaling. Sperm whales have been known to get entangled in deep sea cables when feeding close to the ocean floor. Another human-induced factor is fast becoming a threat. Reports of sperm whales found dead with bellies full of plastic are increasing.

There are fewer than 20,000 blue whales left in the world today. It is estimated that the population has been reduced by 94 percent since before whaling. Blue whales are considered an endangered species in Canada and the United States. In California, policy changes and the banning of hunting have allowed the North Pacific population to rebound to almost 90 percent of what it was before whaling.

At the end of 2020, there were fewer than 375 North Atlantic right whales left in the world. It is estimated their population has been reduced by 98 percent since before whaling. Even more alarming is that only 75 reproductive female right whales remain. The good news, though, is that 17 new calves have been counted for the 2021 breeding season, so there is still hope. However, if we don’t change our actions, right whales could be extinct in less than 20 years. In the last few years off the coast of Canada and the United States, 51 percent of right whale deaths were caused by entanglements, and 37 percent were the result of ship strikes.

What can we do?

We can do so much to help our whales, and it doesn’t matter if we live on the east or west coast of Canada, or in the middle of the country. To start, we can learn more about the challenges these animals face and support the organizations helping to protect them. If you want more information on the North Atlantic right whale in particular, check out the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium website, which provides a full list of the organizations involved (narwc.org).

Fishers, crabbers, governments, and environmental organizations on the east coast are working hard to protect whales. We can do our part by keeping our water clean because all water is connected, especially directly from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

We can also minimize the use of chemicals, pesticides, and other pollutants that go down our drain or from our lawns to the storm sewer and eventually end up in the ocean.

We can reduce using plastics. Switch to reusable water bottles and shopping bags, and eliminate all other one-time-use plastics. Let’s keep plastics out of our rivers, lakes, and oceans.

We should buy local whenever possible. Let’s slow down the amount of shipping traffic around the world and eat responsibly sourced seafood that reduces over-fishing, ensures the long-term health of species, and helps protect the ocean environment. Buy from companies who support the environment, and choose political leaders who care. Our money and our vote matter.

And most importantly, we should get outside, fall in love with the natural world around us, and think about how our actions can have a positive effect on the world.

Excerpted from

Excerpted from the forthcoming publication Great Whales: Up Close and Personal by Mark Engstrom, Burton Lim, Jacqueline Miller, Oliver Haddrath, Mark Peck, and Gerry De Iuliis.