Desire and Design

How eighteenth-century global trade fostered a new-found fascination in plants and flowers from around the world, ushering in a golden age of botany that influenced the decorative arts.

In the 1700s

In the 1700s, plants, flowers, and floral motifs were powerful symbols of social standing in European societies. The prestige associated with florals was a product of European imperialist ambitions and global trade at the time. The French, Dutch, and English East India Companies, among others, imported spices, tea, and luxury goods that, for the most part, were only affordable to the elite and rising merchant classes. The luxury goods included painted porcelain ceramics, Chinese wallpapers, and hand-painted Indian cottons—all decorated with patterns and flowers that were exciting and new. Together, these goods spawned an enthusiasm for a hybrid Asian artistic style that drove the fashions of the day—for the home, and for the wardrobes of the leisured classes.

Western Europeans

Western Europeans were especially eager for the vibrantly coloured Indian cottons (“Indian chintzes”) that, unlike linen, wool, and silk were both washable and colourfast. Indian Chintz proved so popular that Britain and France imposed formal legislation between 1686 and 1774 prohibiting its import and use for dress or furnishings, in order to protect their domestic textile manufacturers. Despite the ban, imports continued.

The British East India Company (EIC) fanned the fires of consumer desire for chintz by custom-ordering designs from India that catered to “English taste.” The English preferred cloth decorated with flowers that were domestic and familiar—rose, tulip, dianthus, narcissus, morning glory, peony, prunus, chrysanthemum, and marigold—often painted on a bright white background, much like Chinese porcelain.

Occasionally, EIC officials

Occasionally, EIC officials altered their instructions, requesting that Indian artisans run with their imagination and create “exotic” designs with rambling fanciful patterns of their country —in this way catering to both the thirst for a perceived Asian artistic style and the growing popularity of “exotic” (non-native) plants in Europe.

European rising interest

European rising interest in plants from other continents in the 1700s related to another aspect of their wider commercial and imperial ambitions. Surgeon botanists working for the East India Companies, and other natural historians travelling the globe, explored distant continents documenting the vegetation, and searching for plants of economic importance or medicinal value to generate trade. Botanical gardens were established in foreign lands and seeds, roots, and shoots of local plants were sent from them to private collectors and botanical gardens on the continent. There, skilled gardeners grew them and developed new horticultural varieties that were more suitable to Europe’s cool climate. Gradually these exotic plants made their way into private gardens and conservatories and were sold in nurseries.

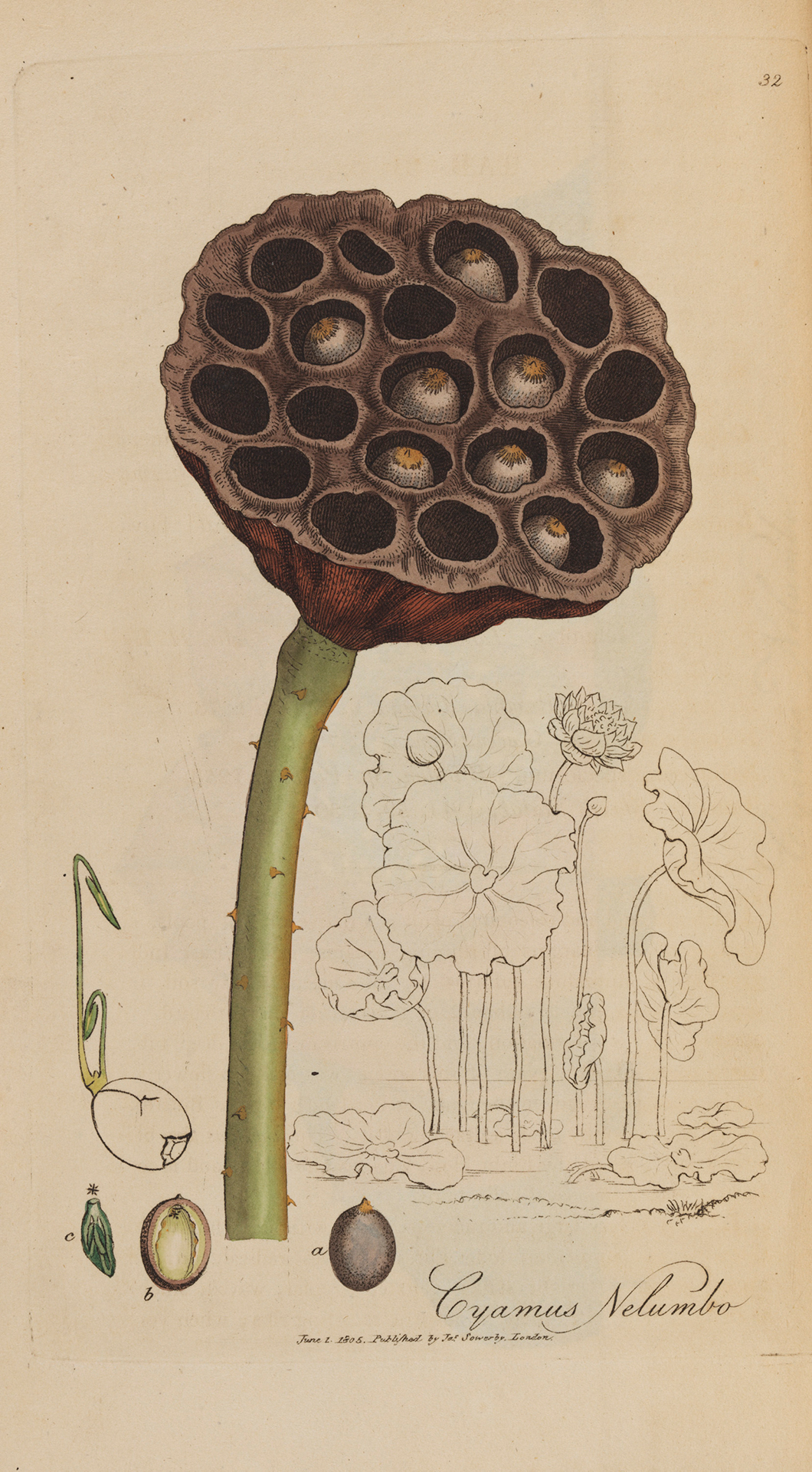

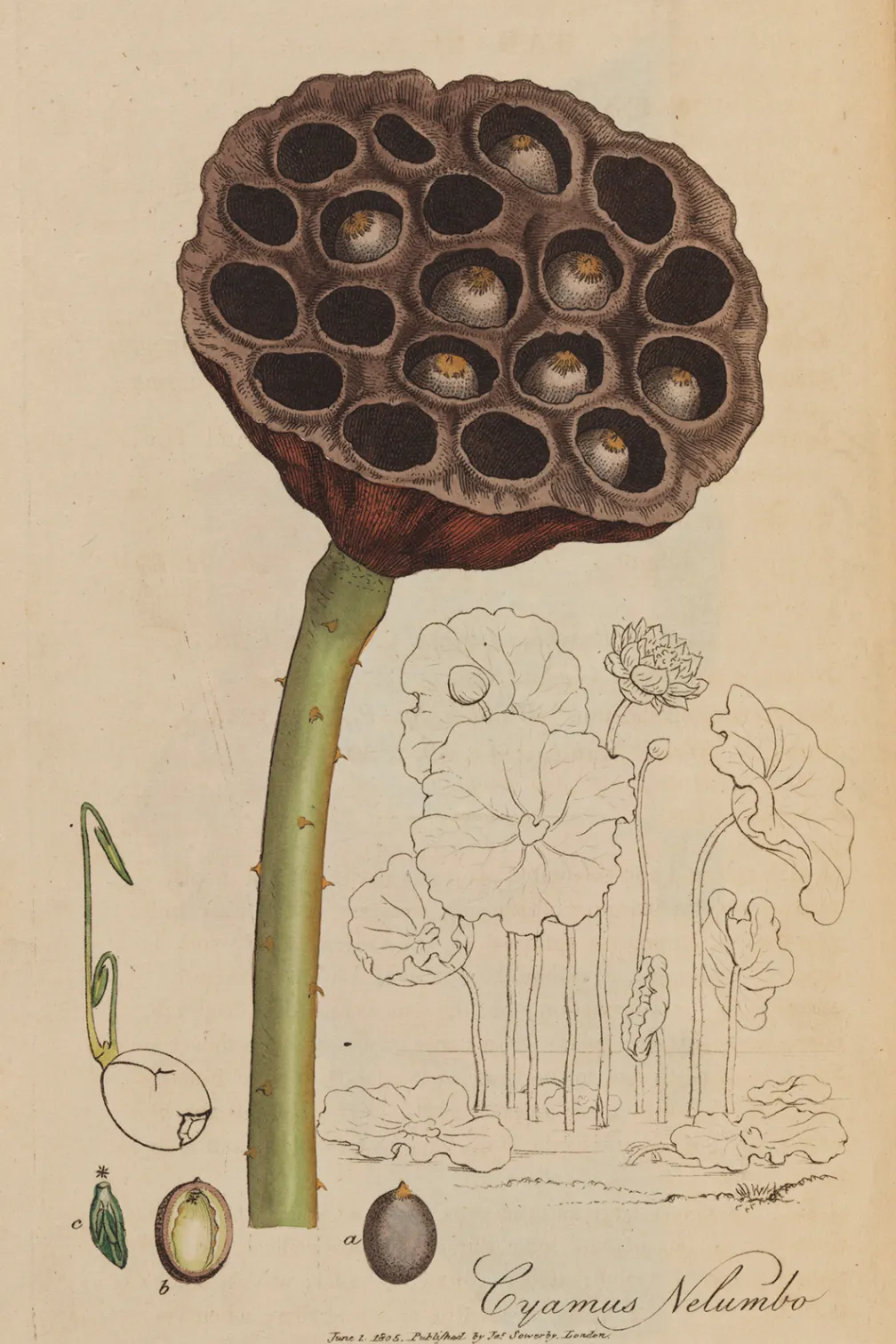

The form, and even the colours of plants introduced from distant continents, were often drastically different than European native plants. The incredible diversity altered European perceptions of the natural world and increased their estimates of the numbers of plants on earth. As the numbers of plants increased, so too did the desire and need for standardized systems to name, describe and organize them. Several botanists devised plant classification systems, but it was the Swedish botanist Carl von Linné (Linnaeus) who revolutionized the process of ordering and naming plants with an easy-to-use sexual system of classification (that divided plants into groups based on numbers of male and female parts) and a binomial nomenclature whereby plants were assigned a generic name and a species name. Linnaeus’ system of names is still used for all living organisms.

The process of describing plants was not left to the botanist and his words alone. It relied heavily on detailed drawings and coloured illustrations of the live plant as a record of the features required to describe and classify it. Scientifically accurate botanical illustrations or “plant portraits” focussed on the flowers and included separate illustrations of each flower part. Thus, the 18th century (1750–1850) ushered in an era that is often referred to as the “Golden Age of Botanical illustration,” when illustrators and flower painters were in high demand to document the newly encountered plants and record the beauty of elite gardens.

Gallery 1

It is in this realm of botanical art

It is in this realm of botanical art that these two parallel stories of global trade and floral fascination—in the decorative arts, and through scientific discovery—intersect.

Advances in engraving and printing technologies made it easier and more affordable to publish botanical illustrations. These works were then distributed to interested patrons in books, magazines, and even nursery catalogues, and became another highly desirable commodity that fed scientific curiosity and provided access to the latest plant fashions. Published botanical illustrations circulated and reappeared as hand painted motifs on ceramics and patterns on textiles, offering additional symbols of social currency for the home. Florals dominated the decorative arts and fashion of the day., and eventually became more widely accessible.

European botanical discoveries and floral desires and designs in the 1700s truly changed the world. They laid the foundation for modern botanical sciences and continue to influence the decorative arts. The plants growing in our gardens the botanical artwork on our walls, and the floral motifs adorning our homes and clothing are all lasting legacies of this era of global trade and floral fascination.

Deborah Metsger

Deborah Metsger is Assistant Curator of Botany at the Royal Ontario Museum.