Sebastião Salgado

GENESIS

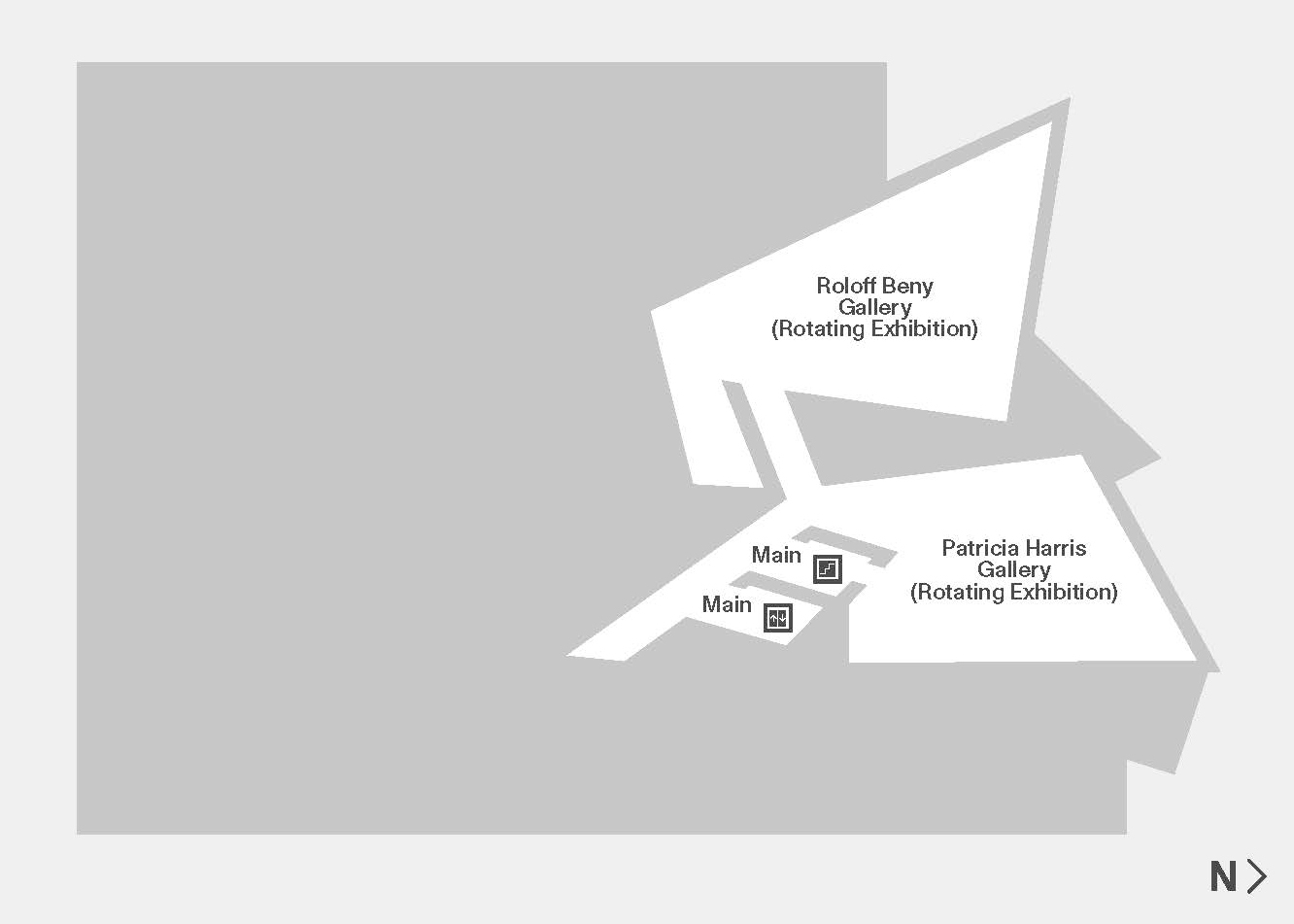

Date

Location

About

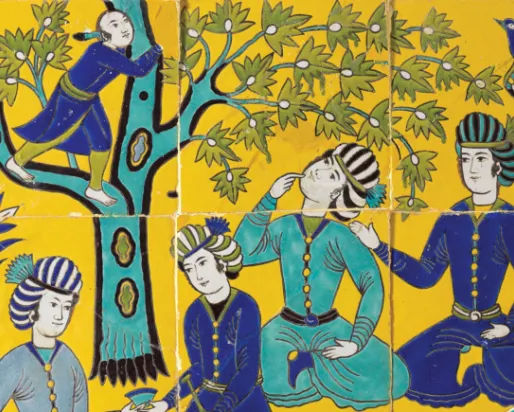

Genesis by internationally renowned photojournalist Sebastião Salgado makes its North American premiere at ROM, organized by Amazonas images, with support of Vale and presented by ROM Contemporary Culture and Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival. Genesis is an eight year photographic expedition traveling to 32 different locations around the planet. Showcasing over two hundred hauntingly beautiful and provocative photographs, Genesis depicts the raw beauty of the landscapes, seascapes and people that have escaped the destructive reach of modern society. Curated by Lélia Wanick Salgado, GENESIS takes you on a journey to rediscover the far corners of the world and urges you to consider what is left of our planet, what is in peril and what is left to be saved.

Highlights

Through innovative exhibitions and contemporary projects, ROM Contemporary Culture provides insight and inspiration to help our community make sense of the modern world and connect with one another. This season, ROM: Contemporary Culture explores the issues of environment and climate change, asking: how does landscape change a culture and how does culture change a landscape?

The Making of Genesis

From May 4 to September 4, 2013, as part of this year’s Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival, the ROM will be home to the North American premiere of renowned photographer Sebastião Salgado’s Genesis, an exhibition curated by Lélia Wanick Salgado. It is his third large-scale photo-project examining global issues. The 245 images in the exhibition have been selected from among the many thousands taken by Salgado during eight years of travelling to 32 different locations. These extraordinary images capture the stunning beauty and epic majesty of areas of the globe as yet untouched by the heavy and destructive hand of human “progress.”

Born in Brazil in 1944, Sebastião Salgado has been called an “icon of social conscience,” “a solo branch of the United Nations,” and “one of the most important photojournalists living today.” Prior to Genesis, Salgado’s exhibition Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age (1986-1992) focused on the struggle and dignity of large-scale manual labour and its gradual passing in the late-capitalist age. Migrations (1993–2000) was a study of the displacement and dislocation of peoples by war and by a globalized world economy that had left them financially and physically vulnerable.

Sebastião Salgado spoke to ROM Senior Curator Deepali Dewan.

DD: Genesis is your most recent in a long line of photography projects. How did it come about?

SS: Every project is born from the previous one. Whenever something has awakened my interest, I have tried to follow it up. Before starting Genesis, I had photographed some very difficult subjects—workers, migration, refugees, wars—and I needed a break. With my wife [Lélia Wanick Salgado, the curator of his work and designer of his books] I had launched an environmental project in southeast Brazil to rebuild the ecosystem of 676 hectares of land that once belonged to my family. The beautiful rainforest I had known as a child had been completely destroyed by unsustainable farming. Lélia and I created Instituto Terra, a non-profit organization, and set about planting close to two-million trees, representing more than 300 species. Slowly we witnessed the rebirth of our forest. From this came the idea that we should go in search of places around the world that are still pristine. During our research, we made the incredible discovery that close to half the planet is still much as it was described in the Book of Genesis. So we designed the project and secured the funding and finally I started to photograph in 2004. The work went on for eight years.

DD: Can you speak about the process of creating Genesis?

SS: We identified 32 different locations around the world to visit. The entire project required detailed organization because some places were inaccessible in winter and others could only be photographed in winter. I was accompanied on most trips by an assistant, Jacques Barthélemy, an experienced high mountain guide. In each place, I also found local guides. On some expeditions, we needed a large team of helpers, on others I worked alone. At different times, I travelled by boat, in balloons, in small planes, by car, and on foot. In the north of Ethiopia in 2008, I walked 870 kilometres across mountains. During this trip, which lasted close to two months, I lived with different tribes.

DD: What role do your photographs of humans play in Genesis?

SS: To photograph the people for this project, I went looking for the nearest I could come to [the Old Testament’s] Genesis, for how we lived 5,000 years ago, 15,000 years ago. This meant finding ancient people in their element, in their environment, where they live unhurried lives in communion with nature. I did many more portraits than I had ever done before. At times, I created a rustic studio and invited people to pose for me. But for the majority of the shots, I simply spent a long time hanging out with people, watching them go about their lives, waiting for things to happen.

DD: Is Genesis intended to move people to make changes in their own lives and in the world around them?

SS: I hope so. But I cannot say that my projects are designed to change the minds of anyone. We are living in an important moment for our planet. The photographs are a way of sharing this historical moment. If my photographs carry this message, all the better. But I have never taken photographs as a campaigner. I’m not an activist. I go to photograph as a photographer. I’m not presenting information as a journalist. Nor am I an anthropologist or a sociologist. For Genesis, I am simply a person curious to explore our planet, to see its landscapes, its flora, its other animals. Until now, I had only photographed one animal: us. Now I found animals as rational as we are. I saw trees that were 4,000 or even 7,000 years old. I discovered that landscapes have personality and dignity. They too are very much alive. In the end, Genesis gave me eight years of freedom to seek out beauty. I hope these images convey the Earth’s strong personality. Ours is a powerful planet to be seen with fresh eyes. For me, Genesis is a kind of respectful poem that we are writing about our natural home.

DD: What was it like shifting to digital photography for the first time during the Genesis project?

SS: I started out working with negatives with a medium-format Pentax camera. About halfway through, in 2008, I switched to a digital camera because I was in constant fear that security machines at airports could destroy my films. A friend assured me that digital images were now of good quality. When I went digital, I switched to a Canon camera and I found the quality was much better than the medium-format negatives. In the final prints, you can see no difference because I have worked with one film, Kodak Tri-X film, all my life, and we were able to reproduce the exact grain of that film in the digital image. We also created a way of working that was no different from how I had always worked. I recorded everything on digital cards just as I did with film and, from these images on the cards, contact sheets and prints were made for me. Those I selected were then made into negatives. So, except for minor differences, the process was exactly the same.

DD: You have talked a lot about the importance of light in your work, light as physical element in the composition. How long have you waited for the perfect light? What is the longest time?

SS: There is no perfect light, or rather, all light I feel is perfect. The light of a photographer doesn’t come from a flash. It comes from inside himself, from his own life and experience. I was born in Brazil where the light is incredible, such a strong light. As a kid, I spent hours looking at light, how it constantly changes. In everything I see, light is important for me. Most of my pictures are taken against the light. This gives so much more volume, much more contour. It’s much more difficult to work like that, but when there’s enough... Sometimes I’ll be walking without a camera when I see an incredible light. I become desperate. I long to have a camera with me so I can work with it. I always work within natural light; I’ve never used any other kind of illumination. I’m a daylight photographer. I go to sleep very early and wake up very early in order to have my daylight in full.

DD: What do you say to critiques that your work aestheticizes struggle, and makes it beautiful?

SS: I don’t make anything beautiful. These subjects are beautiful. When I photograph people around the world, I respect their dignity. Poor for me is not poverty in material goods. Poor for me is someone who doesn’t belong to a community. Rich for me is someone with a sense of solidarity and community. I come from the other side of the planet. And the story that I tell in my pictures is my story, viewed from my perspective. Photography is my language and I write it with the camera as my pen.

Partners & Sponsors

This exhibition is organized by Amazonas images with the support of Vale. Presented by ROM Contemporary Culture and the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival, Sebastião Salgado: Genesis is a primary exhibition of the festival. CONTACT is supported by the Canada Council for the Arts, Celebrate Ontario, the Ontario Arts Council and the Ontario Cultural Attractions Fund.