The Anatomy of a Book: Saving The Naturalist's Library

Published

Categories

Blog Post

Books are remarkably durable. Fragments have survived from ancient times, while others have traversed the centuries in near perfect condition. One such example is the St Cuthbert Gospel from the 7th century, the earliest intact European book. But despite the robust structure of the book, the rigours of use and the passage of years cause many fall into disrepair and to require mending.

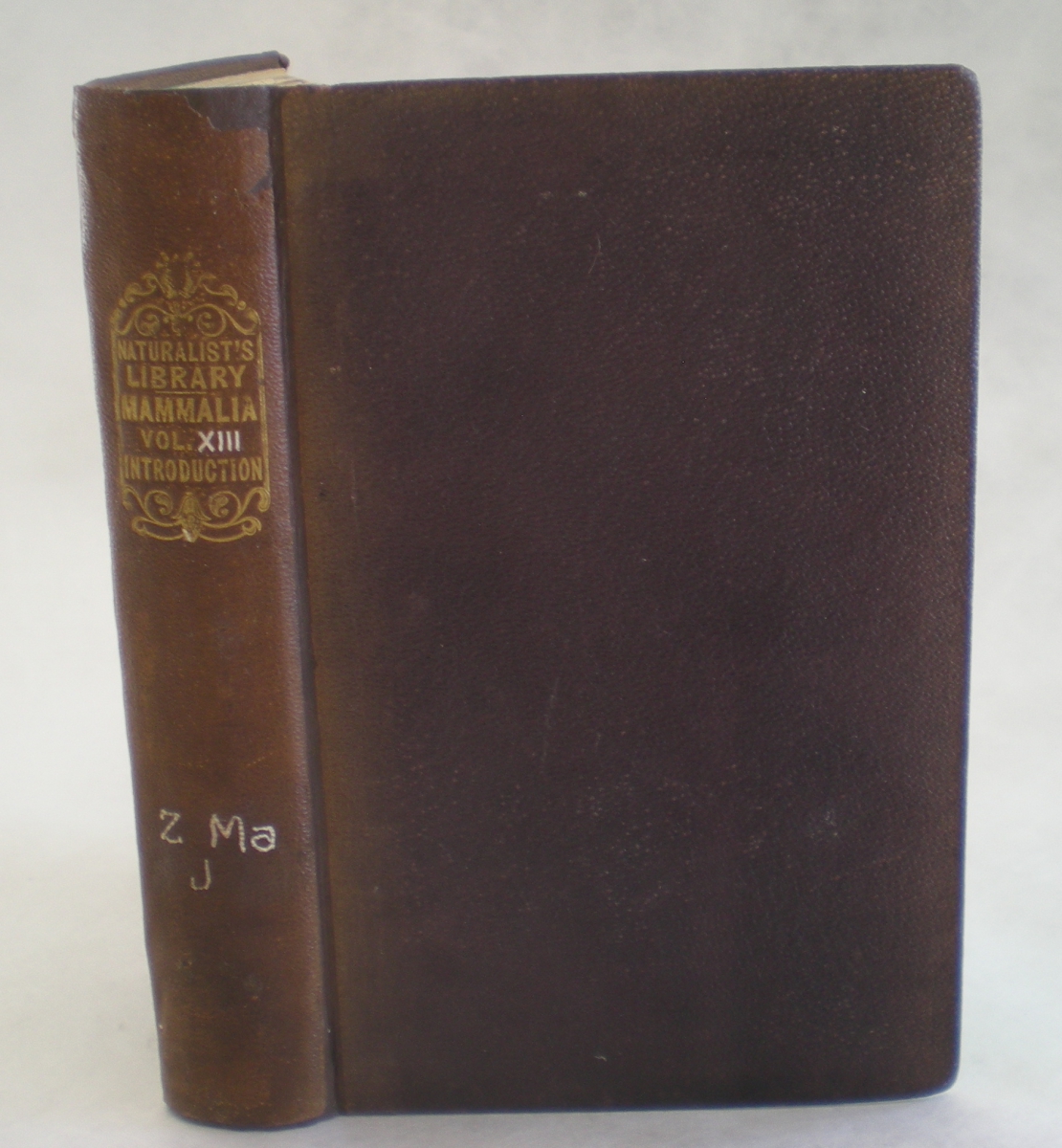

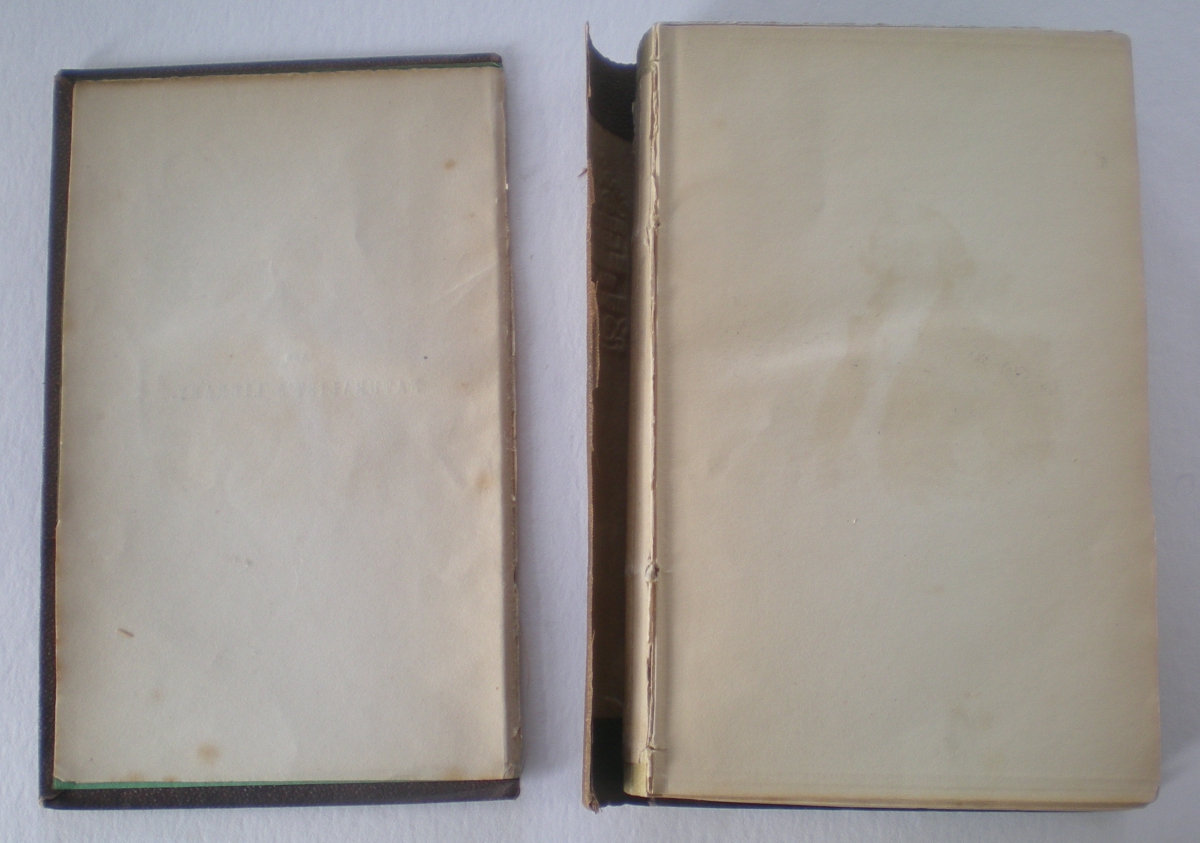

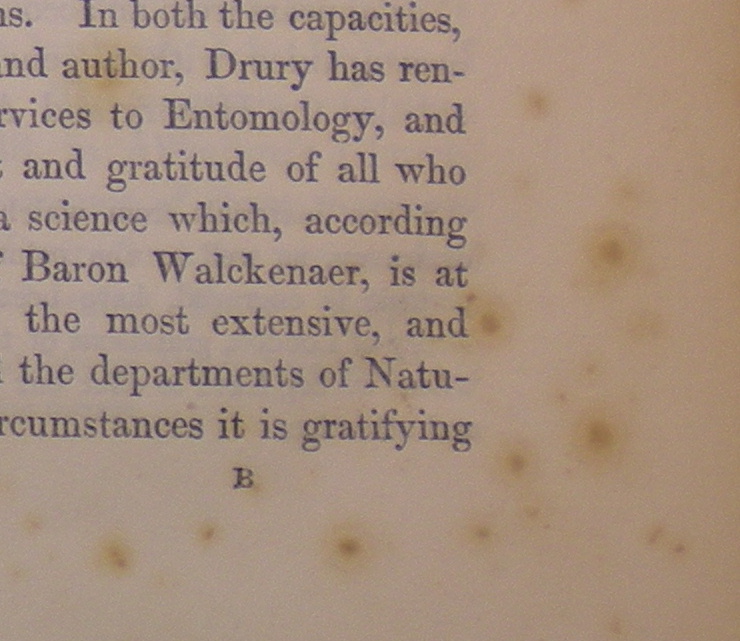

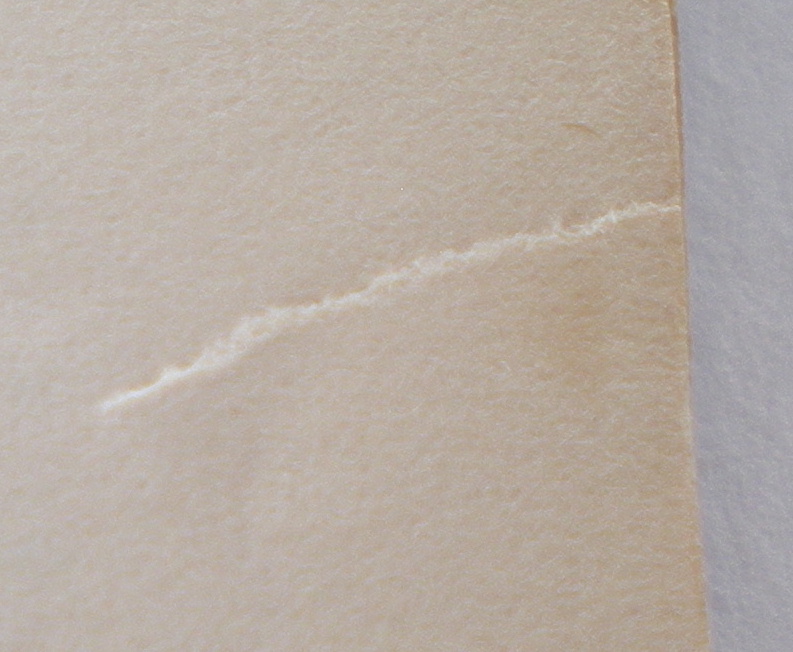

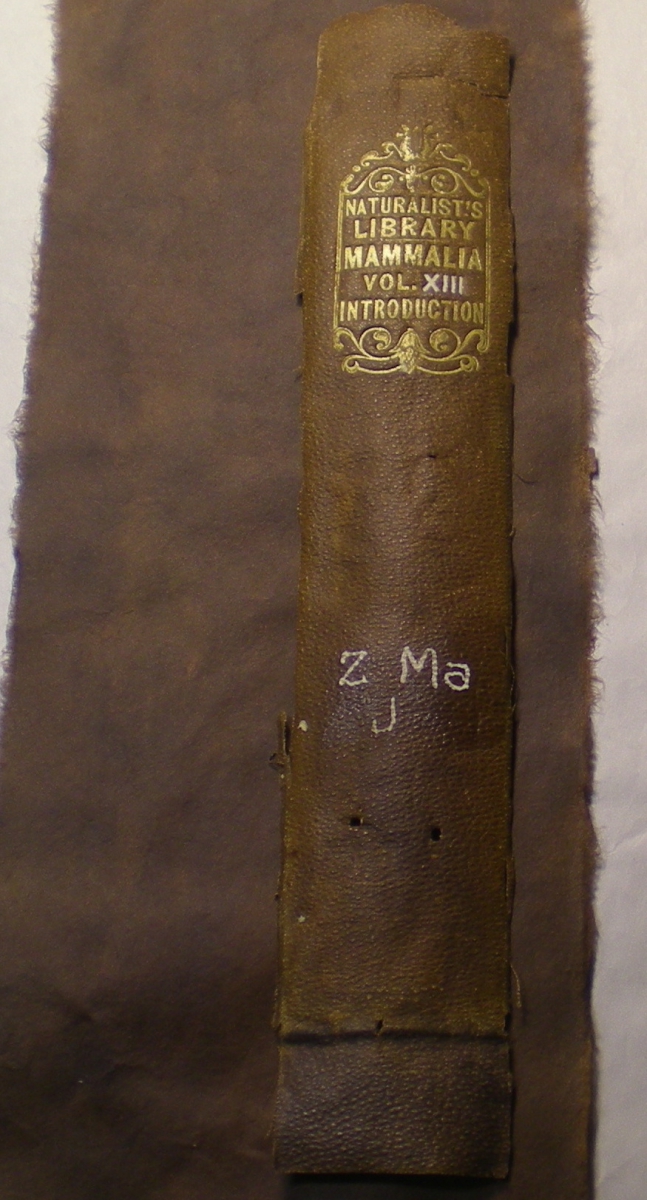

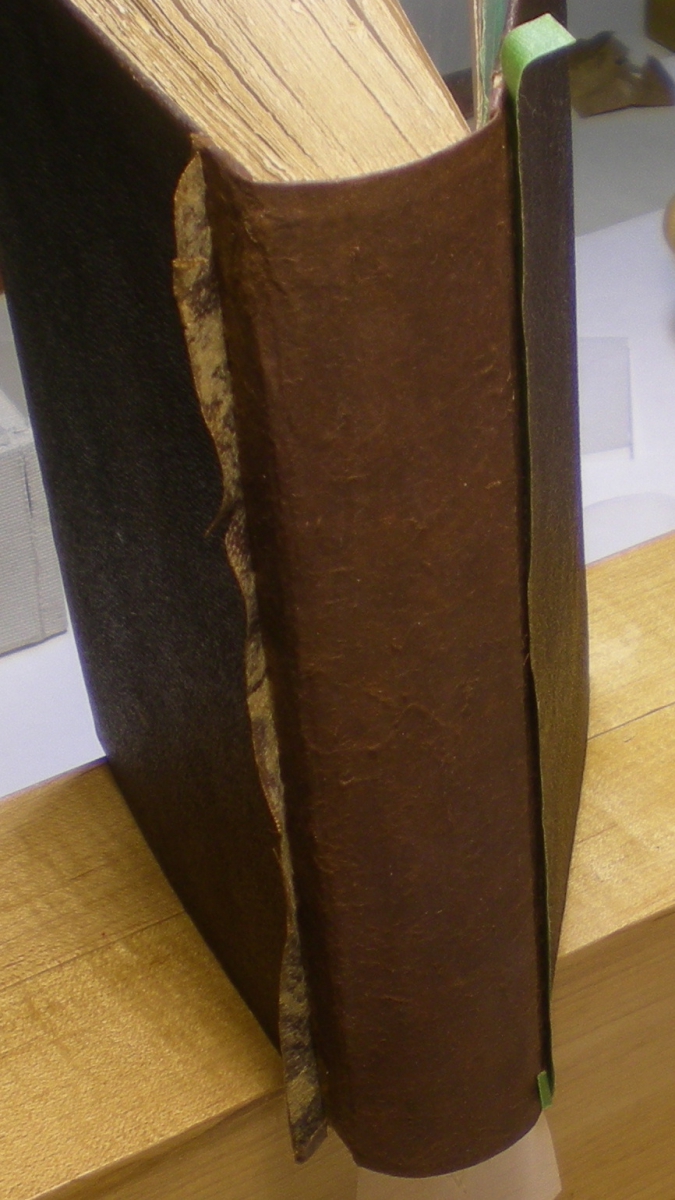

One of the most important duties of librarians and archivists is to maintain and preserve books for future use, and this often means fixing them. One of the ROM books has recently undergone repair and offers a look at how books are made and mended. This is the damaged copy of volume XIII of The Naturalist's Library by Charles Hamilton Smith from 1842. The front cover and spine have fallen away, exposing the binding. The binding stitches have loosened, allowing the pages to slide about in the covers, and some of the pages have been torn.

The modern book is essentially unchanged since late antiquity when the codex form began to replace the scroll. Each book is comprised of three basic parts: the covers, the spine, and the book block.

Book covers are designed to protect the pages inside, and they can be made from various materials. Medieval books often have thick wooden boards as covers, sometimes covered in decorated leathers or rich velvet or brocade fabrics. From the early 19th century on, decorative paper covers became more common, often with a marbled effect. The most common cover material for the codex book is reinforced cloth or leather.

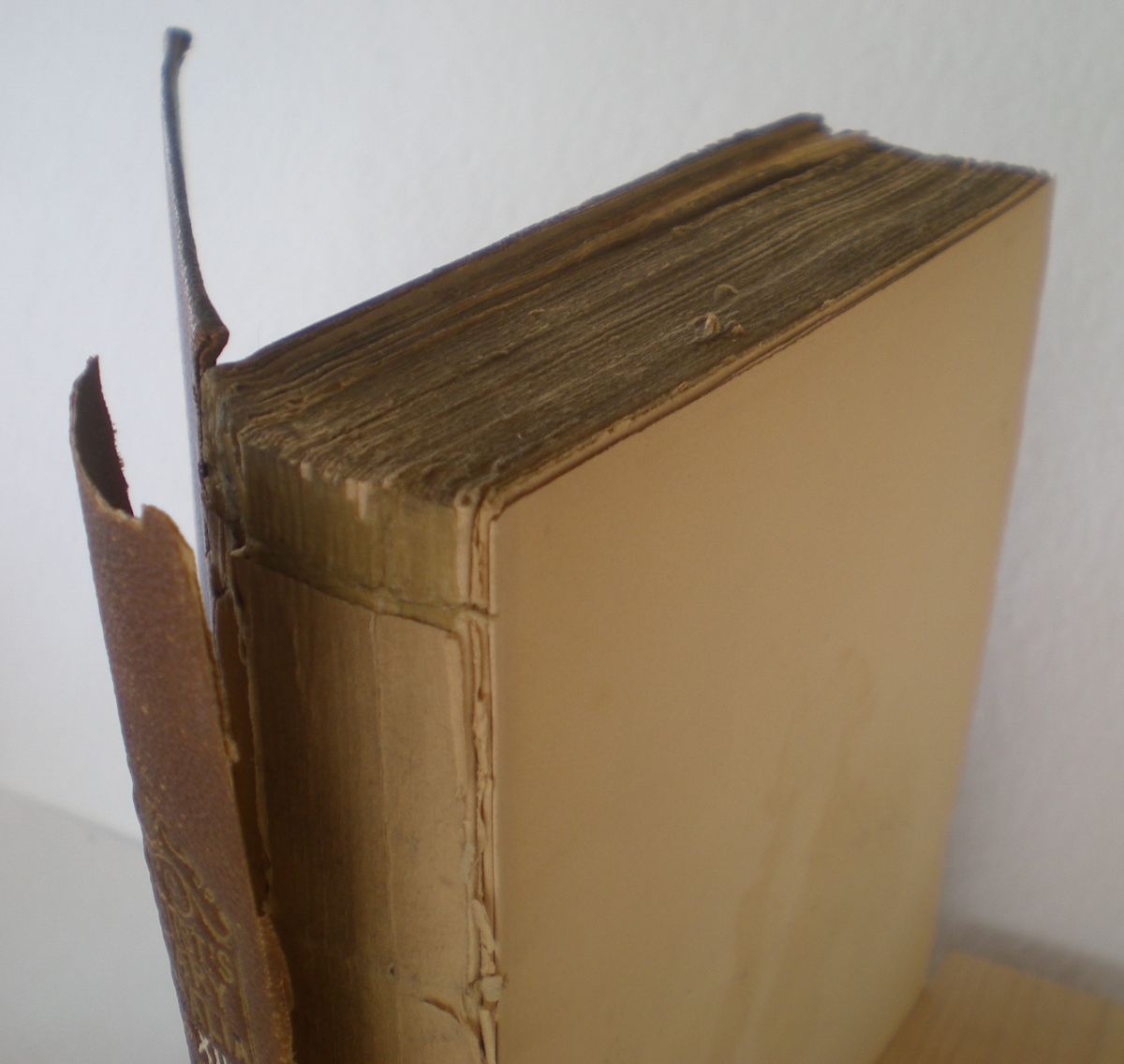

The spine is perhaps the most vital part of the book, and the most vulnerable to damage. The spine keeps the pages together and the more often a book is opened and used, the more stress it endures. There are many kinds of bindings which make up the spine of a book. Modern paperback are usually glued, but traditionally books are sewn together using various stitches. One of the oldest is called Coptic stitch, and was used in Egypt from as long ago as the 2nd century CE.

When constructing a book, a stack of signatures is held together and then pricked and stitched or glued together. Above, the book block of The Naturalist is being pressed and the old glue and loose stitches cleaned and tightened, securing the signatures together again.

The result is a fully repaired book, ready to be used and read for years to come!