How palaeoart brings to life worlds that existed billions of years in the past

Each fossil has an extraordinary story to tell, starting with the amazingly small chance that each one had to become frozen in time—normally, when organisms die, their remains quickly decompose and get recycled through natural processes and very little is left behind, if anything at all. Entering the fossil record provides a real shot at a second—and nearly infinite—“life,” but fossilization is an incredibly rare event.

One problem is that fossilization is usually messy; organisms tend to fall apart quickly after death, or only certain parts of their bodies tend to be preserved. Even after fossilization, remains get compressed and distorted in the rocks, and often eroded or broken up at the surface if they are not discovered quickly. And sometimes, fossils are simply too small or difficult to see to untrained eyes.

Considering all these problems, palaeontologists usually turn to palaeoartists to help them bring fossils to “life.” In this process, palaeoartists collaborate with palaeontologists to recreate stunning visuals, such as paintings, 3D models, or animations. These recreations are the ultimate tools for communicating what life was like in the past. Palaeontologists have always relied on artists to help share their discoveries with their fellow researchers and the public alike.

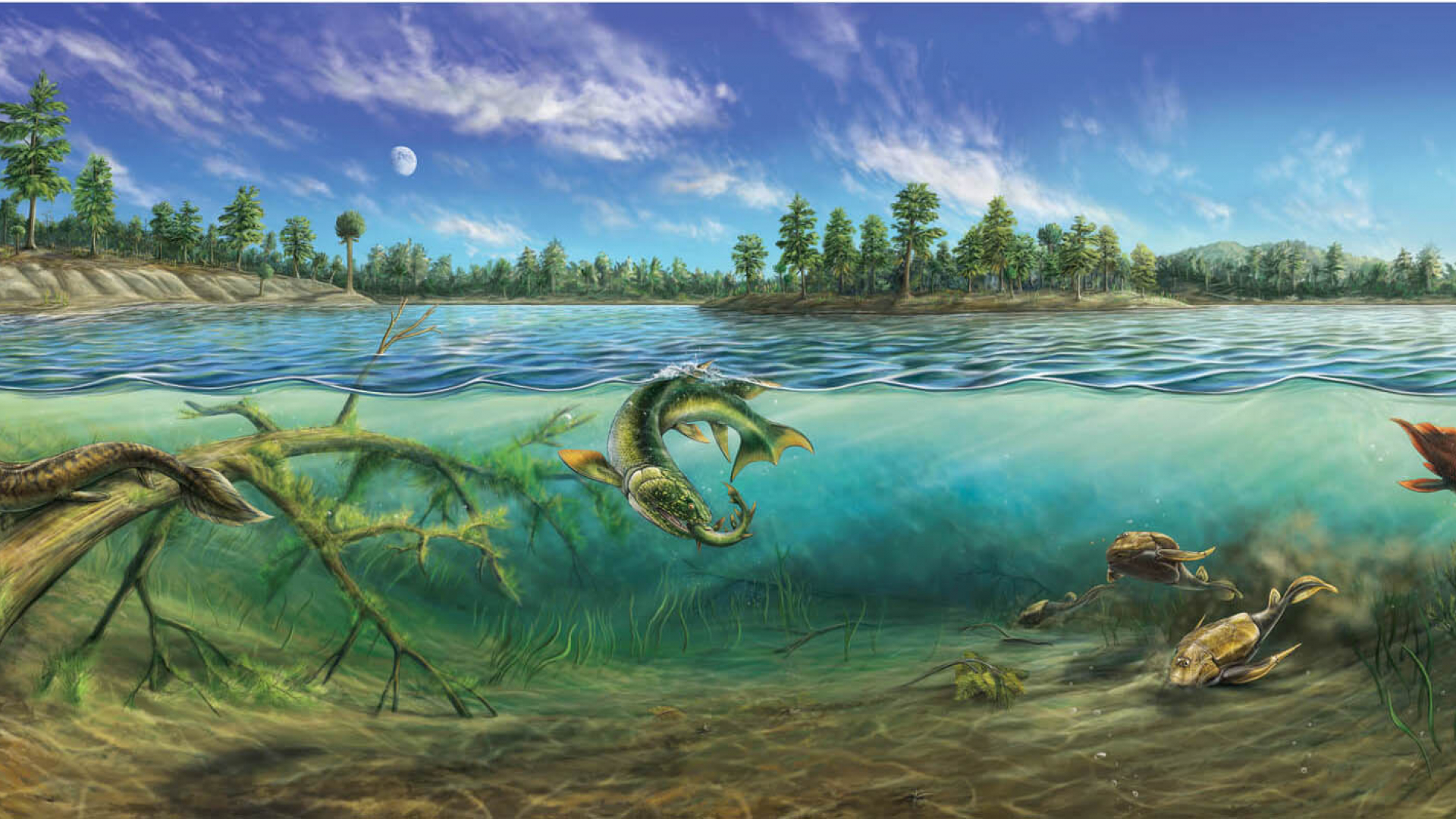

Creating accurate, lively visuals of how fossil organisms looked when they were alive is usually a tedious process, requiring a great deal of time and effort. It is a process that is grounded in the scientists’ knowledge of the organisms and their environments, but requires the artists’ touch to fill in the many unknowns, such as reconstructing missing body parts or colours that were not preserved. Because the colours of fossil organisms are so rarely preserved, artists often choose colours based on comparable environments or organisms living today to create a realistic picture.

For the Willner Madge Gallery, ROM has commissioned many original art pieces from a dozen of the most talented and acclaimed paleoartists in the world, starting with two of our very own staff: Danielle Dufault and Georgia Guenther. Dufault specializes in the rendering of fossil organisms and paleoenvironments in 2D. For the gallery, she worked on the creation of large murals of two of the most iconic Canadian UNESCO World Heritage sites, Miguasha (Quebec) and Joggins (Nova Scotia). Each of the giant graphic walls required hundreds of hours of work to depict the most intricate details of these environments.

Guenther, on the other end, is a sculptor who uses traditional techniques and materials like wax for her artwork. She has been tasked with creating many 3D models, including the spectacular Acutiramus, a giant predatory arthropod which lived during the Silurian Period about 420 million years ago in what is now Ontario and New York State. Guenther’s work is being cast in bronze by Artcast, a GTA-based company specializing in lost-wax casting. The bronze models are meant to be touchable, so everyone can experience the creatures first-hand.

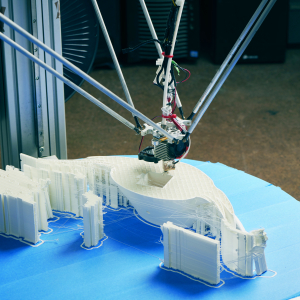

Left: These models were created for Dawn of Life by Georgia Guenther, ROM sculptor and model maker. At the back is Cooksonia, one of the first land plants, with the red algae Waputikia from the Burgess Shale on the right and a wax model of Hylonomus, the first reptile to lay eggs on land, from Joggins, Nova Scotia, on the right. Centre: Toronto-based company Objex Unlimited was tasked with producing small and large 3D prints for Dawn of Life. Here, a cross-section of the body of the largest predator of the Cambrian period, Anomalocaris canadensis, from the Burgess Shale, is in the process of being printed. The finished model has been glued together, retouched, and painted by Guenther and measures nearly one metre in length! Right: Georgia Guenther stands next to Acutiramus, a distant relative of scorpions but which lived in the seas of southern Ontario and New York State about 421 million years ago. Guenther’s wax model reconstruction is shown in the bottom right for comparison.

The transformation of Guenther’s original Acutiramus model from wax into bronze involved scanning the model and then 3D printing it at full size, about two metres long, using a pink resin that looks like bubble gum. This model, a little more durable than wax, was assembled, polished, and cleaned before being used to make a mould that the bronze could be poured into. Everyone in the team is eagerly waiting to receive the finished bronze models of Acutiramus and many other beasts from ArtCast in the Fall.

In addition to traditional sculpted models, Dawn of Life will showcase dozens of computer-generated

Left: These are 3D printed resin models of multicellular organisms from Mistaken Point, a 565-million-year-old UNESCO World Heritage site in Newfoundland and Labrador. These models are used for creating a ceramic shell mould, which will then be filled with melted bronze (centre). Right: After a period of cooling, this is the first view of the bronze cast inside the ceramic shell mould. This is not the end of the process. The cast will then be cleaned and stained with a particular patina before final installation in the Dawn of Life gallery.

The half-billion-year-old Burgess Shale is my favourite site. The Burgess Shale collection is the world’s largest, and new discoveries of global significance are made and published every year by ROM teams and students conducting field-based research there. This site will get a special treat when it comes to digital art. One of the most memorable features of the gallery will be an immersive recreation of the Burgess Shale environment along a 180-degrees curved wall made of 36 OLED screens and covering

These are only a few examples of artworks in this gallery. When you visit the new Willner Madge, Dawn of Life Gallery, look at the beautiful fossils, but also have a look at the reconstructions, models, and animations. They will help you imagine distant worlds from our very own planet.

The Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life is named in honour of Jeff Willner and Stacey Madge, who generously donated toward its creation. Located in the Peter F. Bronfman Hall on Level 2, it features almost 1,000 fossil specimens from ROM’s world-class palaeontology collections.