After looking at the best known of the dubious ‘Minoan’ figurines (which may be modern) in my last post, here I show some of the genuine Minoan objects discovered in archaeological excavations on Crete.

There are similarities between these certainly Minoan antiquities and the ‘Minoan’ figurines without a known archaeological findspot that I discussed previously. These similarities were originally used to prove that the ‘suspect’ figurines were also genuinely Minoan. However, it is now recognized that the parallels are a mixed blessing. On the one hand, they may show that the ‘suspect’ figurines are of the right style to be Minoan, but on the other hand, they provide a model for forgers to copy when creating fake Minoan objects. It is important to consider when each of the Minoan objects was excavated, since this shows which of them were known (and so could be copied) before the ‘suspect’ figurines appeared on the art market.

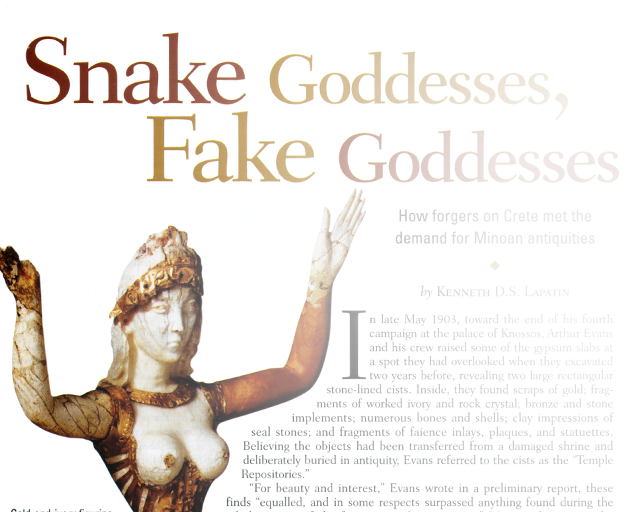

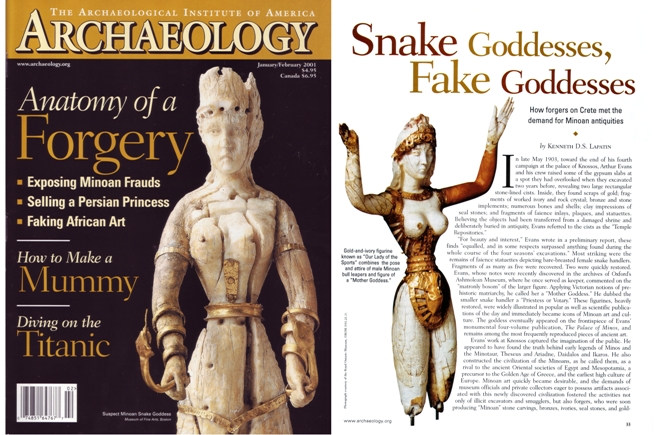

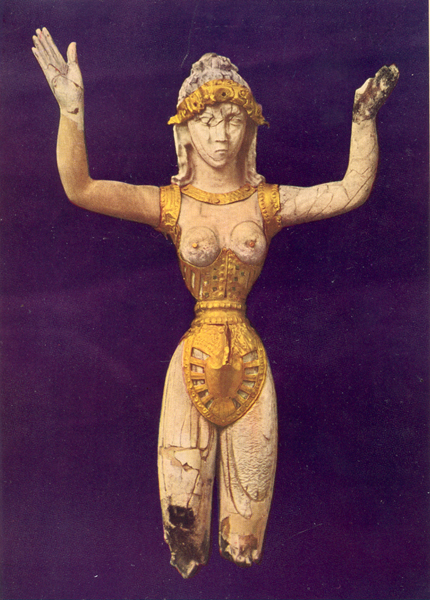

Faience Snake Goddess figurines from Knossos

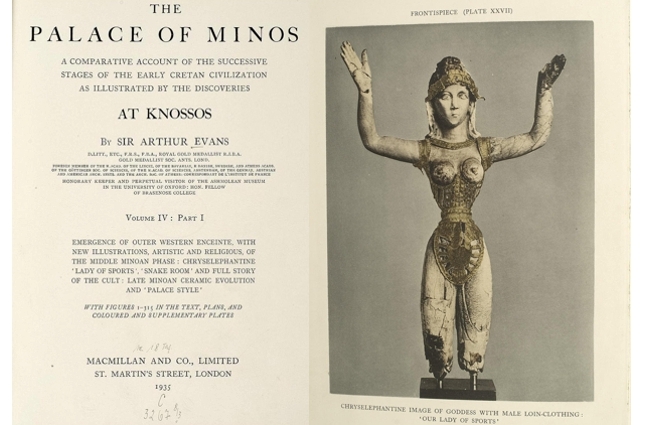

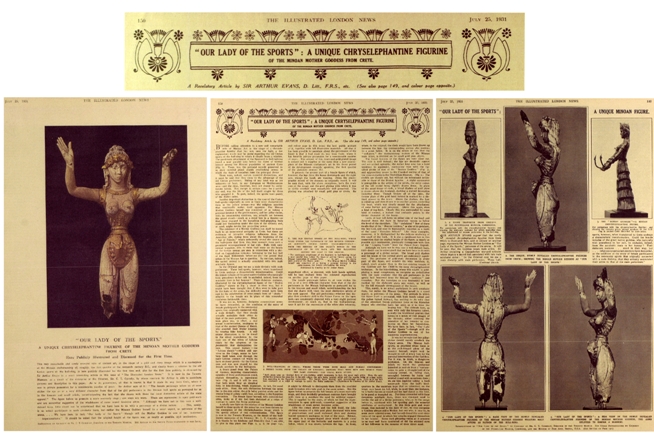

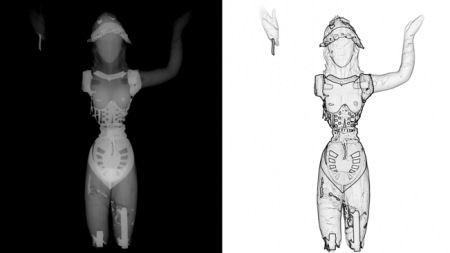

The ‘Shrine of the Snake Goddess’, a “conjectural arrangement” by Sir Arthur Evans of the excavated objects

including the two faience figurines, c. 1600 BC, now in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete

Image from Evans, 'Palace of Minos' volume 1(1921) figure 377

Some of the best known images of Minoan ‘goddesses’ are these two standing figurines holding snakes and made of faience (a glassy quartz ceramic material often used in ancient Egypt). They are very similar in appearance, although not in material, to the ivory Snake Goddesses from Boston and Baltimore.

They were found by Arthur Evans in 1903 in the excavations at Knossos (here on a map), in an area to the south of the Throne Room that he named the ‘Temple Repositories’. Evans believed they represented a Snake Goddess (the figure on the left of the image) and a Priestess, or perhaps another goddess (the figure on the right), and that they were votive objects that were part of a shrine. The image shows his suggested reconstruction of the figurines and other objects discovered with them. This is a highly imaginative reconstruction which unites objects found scattered in at least two deposits and both complete figurines have been reconstituted. The ‘Priestess’ had no head, which was added by Halvor Bagg, a Danish artist, together with the headdress that incorporates (on practically no evidence) a tiny feline also found in the excavations. The face of this figure is pure reconstruction. The ‘Snake Goddess’ was missing the lower skirt, which was restored based of the other figurines and plaques from the excavation area.

Whether or not the details of reconstruction are accurate, the snake-handling women do seem to be associated with some aspect of Minoan ritual. The similarities between these faience figures and the ivory Boston Goddess explains why Evans was so eager to authenticate the ivory figurine when it appeared. He believed that it provided further support for the existence of Minoan Snake Goddess, but for other experts the resemblance was suspiciously convenient.

Ivory Figurines from Knossos

Minoan figurines made of ivory are relatively rare, and have only been excavated in a few areas of Crete. Objects made of carved bone, or ivory strips, such as plaques, inlays, combs and containers are more common, but the craft of carving ivory into rounded figurines seems to have been pretty much restricted to the Minoan Neopalatial period (also called the Second Palace Period, roughly 17th -15th centuries BC). The ivory figurines that do survive are not often well-preserved. Most of the finds are single components of a figure – ivory heads, arms or feet – since many Minoan figurines were made up of several ivory parts joined with sections made of other material that no longer survive, such as wood.

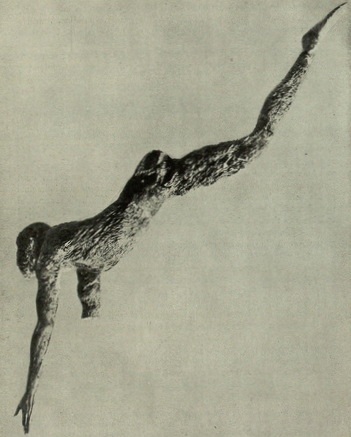

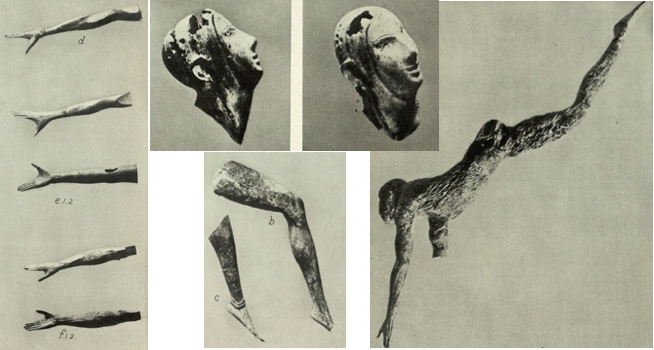

‘Acrobats’ from the Ivory Deposit at Knossos, c. 1600-1500 BC, now in Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete

Photograph from Evans, ‘Palace of Minos’ volume 3 (1930) figures 296 & 297, plate 36

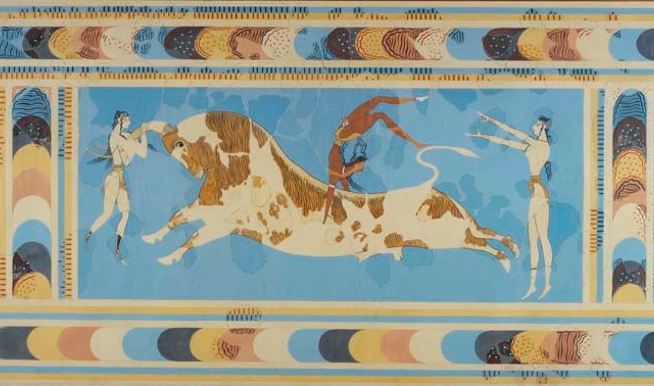

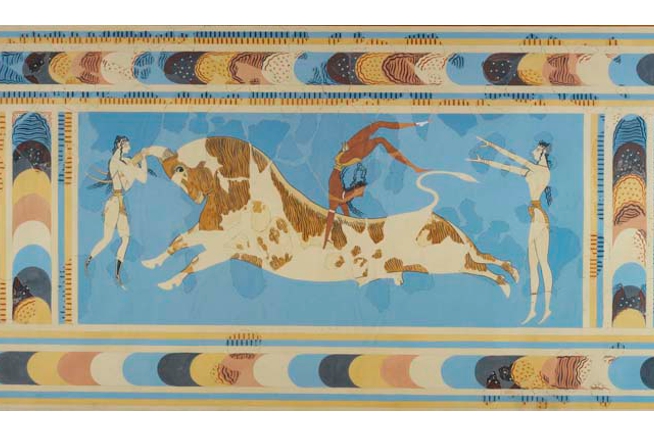

In 1902 the first of these ivory figurines were discovered in Evans’ excavations at Knossos. In the ‘Domestic Quarter’, east of the Central Court, he uncovered what may have been the carbonized remains of a wooden box, which he believed had fallen from the ‘Temple Treasury’ on the floor above. The contents of the box, which Evans named the ‘Ivory Deposit’, included ivory parts from several male figures. These separate limbs included legs and feet, arms with the veins and muscles and even bracelets carefully defined, and heads, with carved features and holes for fixing separate locks of gilded bronze hair. The one figure that was complete enough to be reconstructed was a male acrobat leaping through the air with head tilted back and arms and legs outstretched, almost 30 cm tall. The surface of this figurine is badly preserved, but it was made of separately carved ivory head, arms, legs and torso, connected by a missing section of waist, now restored, but perhaps originally made of wood. The ivory head has holes for locks of hair. In the same deposit was also part of the head of a faience bull, which suggested to Evans that this was once a miniature model of a bull-leaping performance, complete with ivory bull-leapers.

Several other fragments of ivory figurines were found in later excavations in another area of Knossos. In 1956-1962 the ‘Royal Road’ to the north of the Palace was explored in excavations conducted by Sinclair Hood for the British School at Athens. Pieces of ivory male figurines, as well as the possible remains of an ivory-carving workshop were discovered there. The ivory fragments of arms, hands and feet show the same attention to detail of muscles and veins as those discovered in 1902, but they belong to larger figures – originally over 40cm tall – one dressed in a short kilt and another in sandals carved in ivory.

Ivory Figurines from Palaikastro (Roussolakkos), East Crete

For over a century archaeologists from the British School at Athens have excavated at the site of the large Minoan town of Roussolakkos (here on a map), near the modern town of Palaikastro in eastern Crete, and at the nearby Bronze Age mountain-top sanctuary of Petsophas. The excavations have been well-published, and further records are kept in the archives of the British School at Athens.

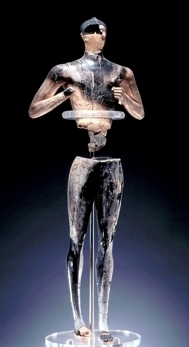

The ‘Palaikastro Kouros’, c. 1525-1450 BC, now in the Archaeological Museum, Sitea, Crete

Photograph reproduced with the permission of the British School at Athens, BSA Excavations Records-PLK 420-PhA 454 © BSA

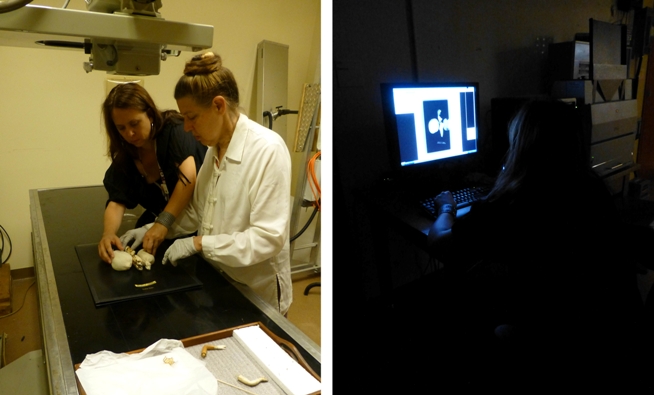

This spectacular figurine came to light only recently, discovered over several seasons between 1987 and 1990 in and around Building 5 to the north of the excavated area at Roussolakkos, during excavations directed by J.A. MacGillivray and L.H. Sackett. It was found in many pieces, some of them badly burnt. When it was reconstructed it proved to be a figure of a youth, around 50 cm tall, and made up of eight ivory sections joined together with boxwood and ornamented with precious materials, such as dark serpentine hair, rock crystal eyeballs, and gold-foil clothes (sandals, and a kilt). Unlike the other Minoan figurines (both archaeologically excavated and ‘suspect’) which were made of elephant ivory, this statuette is hippopotamus ivory – from the lower canine tusks. This is the largest and most elaborate of the ivory figurines known from Crete.

The excavators identified Building 5 as a town shrine, and the ivory youth as a cult statue of a god, perhaps a youthful Diktaean Zeus himself, who, according to legend, was born in this area of Crete, and had a sanctuary nearby from the 8th century BC. They believed that the Building 5 shrine was vandalized and the figurine was intentionally broken and scattered before the whole building was finally destroyed around 1450 BC.

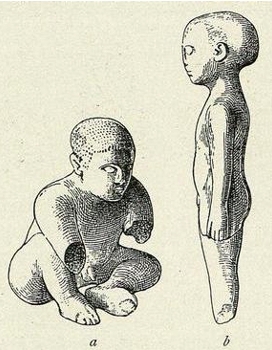

The ivory boys from Palaikastro, c. 1600-1500 BC

Drawing from Evans, ‘Palace of Minos’ volume 3 (1930) figure 310

It was during the first excavation seasons at Roussolakkos, directed by R.C. Bosanquet and R.M. Dawkins, that another pair of small ivory figurines was found in a Minoan house to the south of the excavation area (block Sigma) in 1904. Coincidentally, C.T. Currelly, who would later be the ROM’s first director, took part in that excavation season. These were two ivory figurines of young boys with shaved heads, one seated and one standing. The seated boy, about 5cm tall, was carved from a single piece of ivory, while the standing boy, who is 10.5 cm tall, seems, from photographs, to have separately carved arms attached at the shoulder. When these pieces were excavated, they were believed to be imported Egyptian objects, but they are now accepted as being made by Minoan craftsmen.

Most of the evidence for Minoan ivory figurines comes from these two Cretan sites, but there are examples of fragments which are not so expertly carved, and that suggest that there were several ancient Cretan workshops producing different styles. Finds made in 1980-1982 of small-scale heads and limbs from the Minoan palatial buildings at Turkogeitonia, at Archanes, near Knossos, are more crudely carved. There are also some examples of Mycenean ivory figurines from mainland Greece from approximately the same date that look rather different stylistically. Perhaps the best example is the trio of figures, carved from a single piece of ivory, found at Mycenae and now in the Athens National Archaeological Museum.

One of the most important issues these two posts have raised is how crucial it is to understand, preserve and record the archaeological context and findspot of any antiquities through careful excavation. When we lose the information about where an ancient object was found, either because it was not carefully excavated, or because proper records were not kept, valuable information is lost forever. We don’t know where the object was found, and what else was found with it, and, as my entire investigation into the ROM Goddess shows, we even have difficulty proving that the ‘antiquity’ is genuinely old. There are many current discussions about the damage caused by the looting of archaeological sites and the trade in antiquities. Two good websites that explain some of the issues are Looting Matters (a blog by Professor David Gill) and Trafficking Culture (the website of a research project at the University of Glasgow).

This, and my previous post - The Suspect Sisters (and brothers) - has introduced the objects that most closely parallel the ROM's 'Minoan' goddess. It is through comparisons with these figurines that the ROM goddess has been judged to be a modern fake in recent years, but is this fair? My next step will be to examine the stylistic and technical details of the ROM goddess and consider how they relate to these other figurines. To follow the story of the ROM goddess as it unfolds keep visiting the ROM Minoan Goddess research page.

Further Reading

C.L. Cooper (Kate Cooper), 'Biography of the Bull-Leaper: A 'Minoan' Ivory Figurine and Collecting Antiquity', in Cooper C.L. (ed) New Approaches to Ancient Material Culture in the Greek & Roman World (Leiden: Brill, MGR 27, 2021)

N. Dimopoulou-Rethemiotaki The Archaeological Museum of Heraklion (Latsis Foundation, 2005)

A. Evans, Palace of Minos: A Comparative account of the successive stages of the early Cretan civilization as illustrated by the discoveries at Knossos (Macmillan London, 1921-1935)

Faience ‘Snake goddesses’ from the Temple Repositories: Volume 1 (1921) pp. 495 ff

Ivory ‘acrobats’ from the Ivory Deposit: Volume 3 (1930) p.428 ff

Ivory boys from Palaikastro: Volume 3 (1930) p. 446 & Plate XXXVII

S. Hemmingway, ‘Art of the Aegean Bronze Age’ The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin v. 69 no. 4 (Spring 2012)

K. Lapatin, Mysteries of the Snake Goddess. Art, desire, and the forging of history. (Boston & New York, 2002)

J.A. MacGillivray, J.M. Driessen & L.H. Sackett (eds.) The Palaikastro Kouros, A Minoan Chryselephantine Statuette And its Aegean Bronze Age Context (British School at Athens Studies 6, 2000).

A Virtual tour of the Archaeological site of Knossos by the British School at Athens (this needs a plug-in such as Quick time player)

With thanks for assistance and picture permissions to Catherine Morgan and Amalia Kakissis (The British School at Athens)