Martians among us

With the announcement of three new Martian Meteorites in the ROM’s planetary science collection, recent evidence of flowing water on Mars, and of course, the success of the Hollywood movie “The Martian”, it seems fitting to sit down and take a closer look at the Red Planet. And we can do that here at the ROM, because we are one of the most important international collectors of Martian rocks IN THE WORLD! Out of only 100 Martian meteorites found here on Earth, the ROM has samples of 22 of them (12 are considered ‘main masses’, which means that they are the largest known piece of a particular meteorite). Many of these samples have been acquired and donated by ROM Research Associate Dr. David Gregory, whose passionate interest in meteorites was sparked by a school visit to the ROM years ago.

Here are some of the most common questions we get asked about our Mars samples.

How do we know they’re from Mars?

Over 30 years ago scientists were puzzling over some unusual features in a meteorite which had been found in the Antarctic. They noted that there were dark veins and patches in this meteorite which turned out to be glass. It wasn’t like the glass we see in windows or bottles, but a type of natural glass formed from the rapid melting and then equally rapid cooling of certain minerals such as feldspar, which occurred in this meteorite. Such glasses are often formed as the result of a brief but intense pulse of pressure: a shock wave moving through a rock. These kinds of shock waves are known to occur when asteroids collide since such shock glasses are commonly seen in other types of meteorites.

Image Credit: Natural History Museum

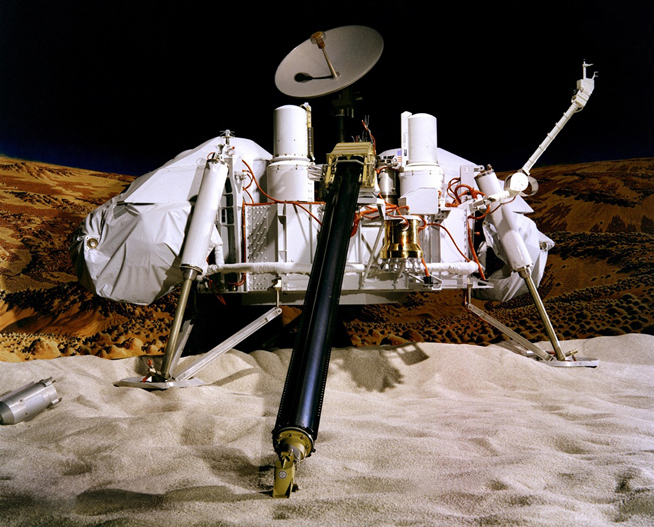

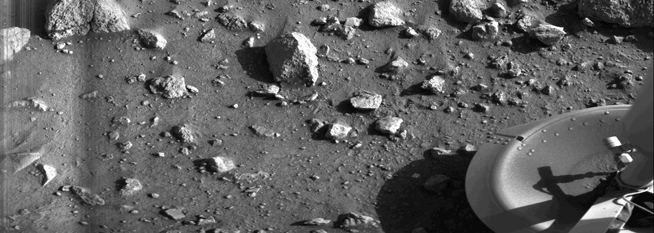

What made this glass different was that it contained small vesicles – cavities – which, upon close analysis, turned out to contain gases. As luck would have it (and there is often a good degree of luck in science) the two Viking probes launched by NASA had landed on Mars in 1976 and measured the Martian atmosphere. It turned out that the gases extracted from the mystery meteorite were an exact match for gases such as neon, nitrogen, argon and carbon dioxide measured on Mars. As the saying goes it was a slam-dunk and the source of the mystery rock was identified. Since then at least five other Martian meteorites have produced the same results confirming the original finding.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

Image Credit: NASA

How did they get here?

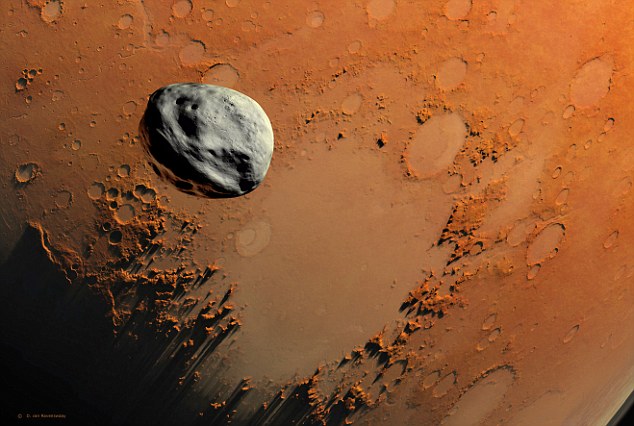

How they got here is hinted at in the first question. The energy released during the impact of a large meteorite or asteroid onto a planetary body is unimaginably extreme and can be in the order of millions of pounds per square inch. This energy is released instantaneously upon impact creating the shock waves mentioned above. This energy can also, if the impacted body is small enough, literally blow material off the surface and launch it into space. Mars is less than half the size of our planet and so has much less gravity. The most likely mechanism, then, for there being Martian rocks on Earth, is that they were blown off the Martian surface during large impacts; and with a great deal of luck they made it to the Earth and were discovered.

Image Credit: Planetary Science Research Discoveries

Image Credit: Daily Mail

How many are there?

More Martian meteorites are discovered nearly every year, so the total number changes regularly. But currently there are just over 100 Martian rocks on our planet.

What are they made of?

Just as with Earth-rocks not all martians are the same. There are three basic types: shergottites, nakhlites and chassignites. These names come from the type localities, the place where the first piece was recognized, Shergotty, India; Nakhla, Egypt and Chassigny, France. These three basic types vary in their mineralogical composition but the interesting things is that, despite being from another world, they are surprisingly similar to terrestrial rocks. They are composed largely of three common minerals: pyroxenes, feldspars and to varying degrees olivine. Such minerals compose rocks on Earth that we generally refer to as mafic, an acronym meaning that the minerals in these rocks are rich in elements such as magnesium and iron (or in Latin, ferrum hence the “f”). In fact the crusts of the 4 terrestrial planets – Mercury, Venus, the Earth-Moon system and Mars – are all composed of mafic rocks. What this tells us is that, at least in bulk, the four terrestrial planets formed from the same types of materials.

Image Credit: NASA

Why are they important?

Samples of other worlds allows us to understand the Earth better. We have learned a good deal about our planet: how it formed, what it is composed of, how it functions; but much of this knowledge is theoretical and needs to be continually revised as we learn more. Having the opportunity to study how another planet formed gives us a reference point, something we can compare, contrast and test our theories against. We think this or that may have happened here. Has it happened elsewhere in the solar system? Has something else entirely different happened that we hadn’t thought of? And of course as talk increasingly turns to sending humans to Mars or even colonizing it, having some idea of what to expect – geologically speaking – before you get there would be a good thing. If a colony is to survive there they will need, eventually, to extract all their resources from the surface of that planet. Is that possible? The rocks are our only way to find out.

The ROM’s collection of minerals, gems, meteorites and rocks is on display in the Teck Suite of Galleries: Earth’s Treasures. Visitors can share their own samples of meteorites, rocks, minerals, gems, and fossils, at the ROM’s Identification Clinic on December 9, 2015 at 4:00 pm. Come explore the ROM’s meteorite collection during the ROM for the Holidays: Planet ROM program, Dec. 26, 2015 – Jan 3 2016.