North Africa is very hot and dry. The Sahara would stretch right across from near the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea if not for the Nile River. The Nile has allowed people to live in Egypt and develop a great civilization. The dark rich soil deposited by the annual flood, the Inundation, enabled farmers to grow two crops a year. During each flood, however, all the fertile land was flooded, and property lines and low-lying structures were washed away.

When the Ancient Egyptians buried their dead, they did not want the bodies to be washed away by the floods, nor did they want to use up valuable farm land for cemeteries. The dead were buried close to the villages of the living, in the higher, dry deserts that flanked the Nile.

These deserts are so dry that bodies placed into them will quickly lose all moisture. Without moisture, the bacteria which cause decay will not be able to survive, and the body will simply dry up – a natural mummy.

The Egyptians must have found many natural mummies over the centuries before the Age of the Pyramids. Knowing that it was natural for a body to be preserved, the Egyptians may have felt that it was unnatural for it to decay, and that there must be some important reason why bodies did not decay, but retained their hair and skin, and continued to be recognizable for many years after death.

Most preserved bodies of Ancient Egyptians from the Age of the Pyramids are natural mummies. There are far more skeletons, however, than mummies, in the tombs of the Age of the Pyramids. Bodies are less likely to be preserved if buried in fine tombs, than if left in the sand. Why?

The problem with burying bodies in the hot dry sand is that, although the body is safe from decay, it is not safe from animal scavengers, nor from thieves who might dig the body up to take jewellery or other grave goods. To keep bodies safe, the Egyptians began, about five thousand, five hundred years ago, to bury some people in very large baskets, wooden boxes, or underground tombs with stone floors. Unfortunately, while these burials were often perfectly safe, without the contact of hot sand to speed the drying process, the flesh rotted, leaving only skeletons.

Because the natural course of events in Egypt was for the body to be preserved and to remain recognizable after death, the decay of bodies which were carefully protected in fine tombs was unacceptable.

Two methods evolved to preserve bodies artificially: linen and plaster and natron.

Linen and Plaster

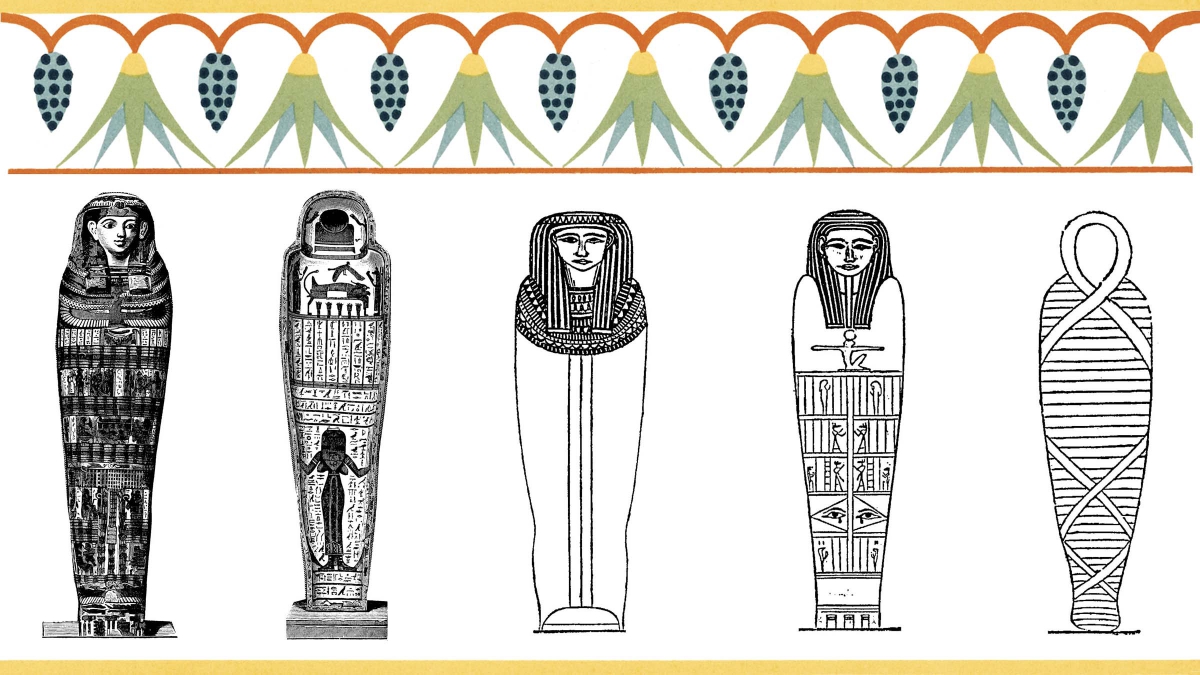

The first method of preservation was to wrap the body in as many layers of linen as possible. Individual fingers and toes were wrapped separately, and the whole body, when wrapped like this, kept the form of a human being. [These mummies look like the ones in movies and comic books.]

Sometimes plaster was smoothed over the face and body, to preserve the appearance of a human being even better. The face might be carefully modeled to look like the deceased. Hair and facial features, such as moustaches or prominent eyes, could be indicated.

Bodies treated in this way show what the people looked like in the Age of the Pyramids. The body beneath the wrappings, however, is usually skeletal. Linen stiffened with plaster or gesso is called cartonnage and was used in mummification until the beginning of the Christian era.

Natron

Natron is a kind of salt that occurs naturally in Egypt. It can be dug up in the Wadi Natrun, and other places. Its chemical composition varies from one place to another, but the best is more or less half sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) and about the same of sodium carbonate (washing soda), with sodium chloride (table salt) and sodium sulfate as 'impurities.' Poor quality natron is almost all sodium chloride.

In mummification, this salt takes the place of the hot, dry desert sand. The process is actually rather similar to preserving fish or meat by desiccation. The body is placed on a special table, perhaps on a layer of natron, and covered with natron. Natron was also used internally. Small packets of it were made up and put inside the body cavity to speed the drying process.

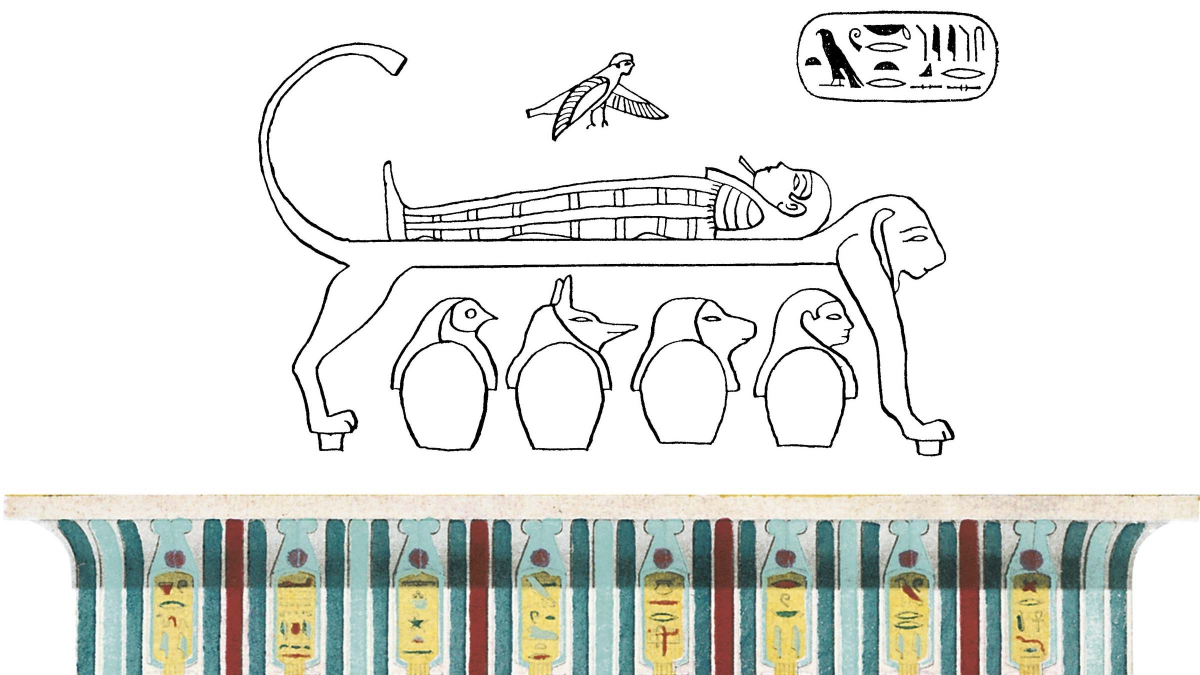

The Ancient Egyptians did not discover the best way to mummify a body all at once. During the Age of the Pyramids, there were many experiments. One important observation was that the internal organs, because of their moisture, would rot quickly, and should be removed if the body was to be preserved artificially. The lungs, stomach, liver, and intestines were taken out of the body, dried out separately, and placed in four canopic jars. During the Old Kingdom, these jars had simple flat lids. They were placed in a separate stone compartment in the burial chamber of Fifth and Sixth Dynasty pyramids. A canopic jar of Pepy I has been found, intact.

At some times, a solution of natron in water seems to have been used to 'pickle' the dead person. The evidence for this comes from canopic jars. The organs of the Fourth Dynasty queen Hetepheres, the mother of King Khufu, for example, seem to have been preserved in solution. Because there was a very long delay (over two hundred days) between the death and burial of Queen Meresankh, also of the Fourth Dynasty, it is sometimes argued that she was mummified by being placed in a solution of natron. Experiments have shown at a 4% solution of natron will preserve small animals, but to preserve a human body in this way would require a very large containers - something bigger than a bathtub - for the liquid and the body, and no such containers have ever been found.

Burial Customs

We know nothing about the funerals of ordinary people, but the decoration in Old Kingdom tomb chapels tells us a little about the funerals of nobles. The Pyramid Texts and the layouts of royal mortuary temples give us some idea about rituals surrounding the death of the king. Although there were changes to this ritual over the next two thousand years, the changes were surprisingly minor. Evidence from the New Kingdom and Late Period suggest that the rituals that had once accompanied only kings and nobles later were performed for small landowners and craftsmen. How were the masses, the farmers, taken to their eternal rest? We do not know, but the Middle Kingdom text, The Dispute of a Man with his Ba, offers a sad image of the resting place of the very poor.

Those who built in granite, who erected halls in excellent tombs…their offering stones are desolate, as if they were the dead who died on the riverbank for lack of a survivor.

In the Late Period, the story of Setne Khaemwase and Sa-Osiris offers another thought about the burial of the poor. Prince Khaemwase looks out of his window and saw the rich funeral of one man, and the pathetic lack of ceremonies of another. Saddened at this sight, he is reassured by his son, Sa-Osiris who takes him on a tour of the Underworld:

My Father Setne, did you not see that rich man, clothed in a garment of royal linen, standing near the spot where Osiris is? He is the poor man whom you saw being carried out from Memphis with no one walking behind him and wrapped in a mat. They brought him to the netherworld. They weighed his misdeeds against the good deeds he had done on earth. They found his good deeds more numerous than his misdeeds in relation to his lifespan, which Thoth has assigned him in writing, and in relation to his luck on earth. It was ordered by Osiris to give the burial equipment of that rich man, whom you saw being carried out from Memphis with great honours, to this poor man, and to place him among the noble spirits, as a man of god who serves Sokar-Osiris, and stands near the spot where Osiris is.

Soon after death, the body was taken to the wabet, the 'pure place,' where the embalming actually was carried on. This appears to have been a tent, away from residential areas, on the edge of the desert. The dry heat of the desert air and the sun pounding down on the linen roof would have speeded the drying process. Drying and wrapping took about seventy days. The formal mourning period may have coincided with the embalming. During the New Kingdom, the process of mummification began in the Per-Nefer - the House of Beauty.

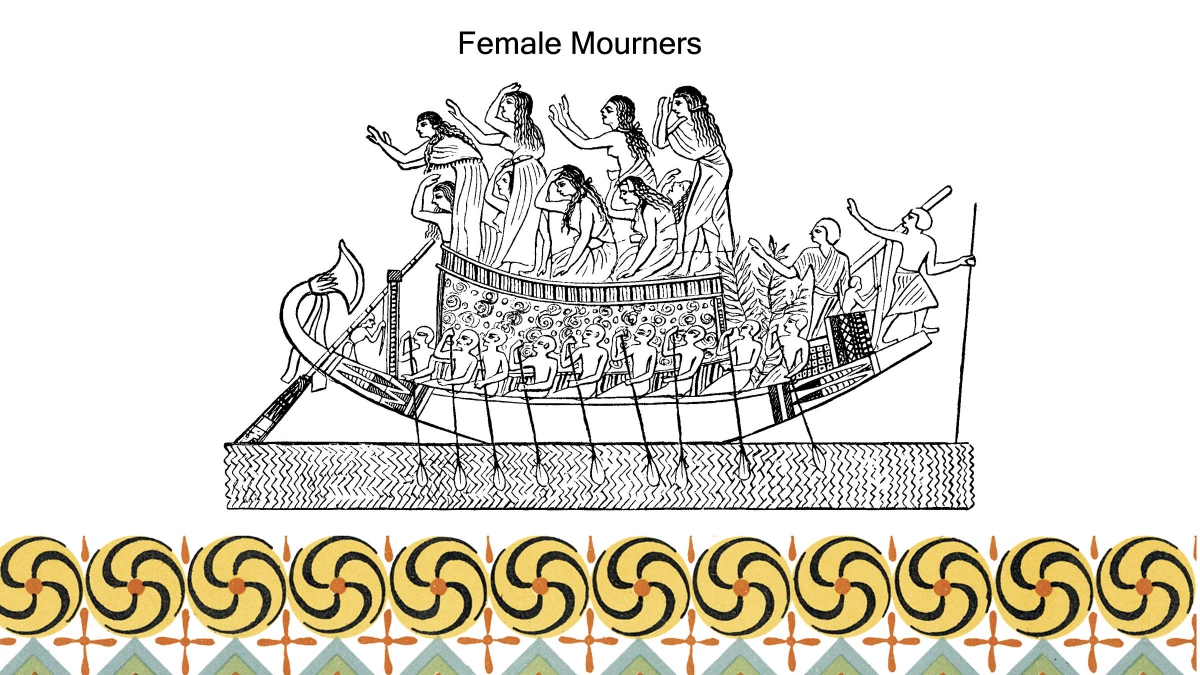

The tomb of Ankhmahor shows the body of the tomb-owner being taken from his own home, amid much weeping. Two women play the roles of the goddesses Isis and Nephthys; they are called the djeret mourners. The women who performed these parts may have been professional ritual practitioners, or members of the family. Tombs of the Nobles, and even of the Craftsmen of the New Kingdom, show the same ritual djeret mourners, who may have been family members or professionals, hired for the event.

The body was ferried across the Nile from the East Bank, where the living dwell, to the West, the land of the Dead. The coffin would then be dragged on a sledge from the water's edge to the tomb itself. In the case of kings, the mummification may have been carried out in the Valley Temple, and the body then dragged up the Causeway to the Mortuary Temple at the base of the pyramid. Craftsmen performed the funeral ceremonies for their friends, and seem to have carried the mummified body to its tomb, much as pallbearers carry a coffin.

In front of the tomb, lector priests read out prayers, and burned incense before the coffin and the ka statues. For kings, there would be dancing and singing by priestesses, and sacrifices of animals. Richer nobles probably had similar ceremonies, on a smaller scale. Singers and dancers could be hired for such occasions.

A procession carried the wordily possessions of the dead person to the tomb. Considerable amounts of cloth, cosmetics and furniture, as well as the traditional food offerings were placed in the tomb.

Finally, when the coffin was in its place, a ritual practitioner would perform the Opening of the Mouth ceremony, probably on the ka statue, to enable the dead person to see, hear, breathe, eat and speak again.

One of the last acts of the ritual practitioners would be to sweep footprints from the floor of the burial chamber.

The final part of a funeral was a funerary banquet, (perhaps somewhat like an Irish Wake) at which the relatives and friends of the deceased, sure that everything possible had been done for the safety of their loved one, could relax a little, and remember the good times

It was the priests and bureaucrats of the Twenty-First and Twenty-Second Dynasties who collected the ravaged New Kingdom mummies from their tombs in the Valley of the Kings and reburied them safely, but without glamour, in old tombs. During their clearance of the Royal Tombs, they had the opportunity to observe hundreds of mummies. As robbers had often torn the bandages in search of jewellery, the bodies had been laid bare.

For perhaps the first time in Egyptian history, embalmers could examine the results of their predecessors' work. They clearly thought that even the best of previous attempts had not been completely successful. Embalmers of this period tried to improve upon the New Kingdom model. They sometimes introduced packing of sawdust, natron, or other materials under the skin. They added false eyes of faience or stone.

Bodies were even painted, red-brown for men, yellow for women, and 'make-up' applied to faces, to enhance their life-like appearance. Wigs of twisted yarn were sometimes placed on the body or woven into the mummy's natural hair.

Unfortunately, these attempts to recreate a life-like appearance were not always successful. The packing materials could swell up, giving the body a very plump or even pregnant appearance, or burst through the skin, leaving a cracked, very unattractive face.

Perhaps in an attempt to make the body more complete, or perhaps because they had seen that canopic jars were often smashed by robbers, the embalmers now often wrapped the internal organs and then returned them to the body cavity. The canopic packages might also be placed inside the coffin, between the legs of the mummy.

Artificial Mummies

A great many mummies remain from the later periods of Egyptian history, and it is these that are usually encountered in museums. The bodies of the royal dead from these periods have not been found, and so we cannot know what treatment was available at the upper end of the scale. Therefore, this description applies to the bodies of the middle classes.

Some are almost as well made as those of the New Kingdom, some are very poorly preserved. The painting of bodies continued, and so did experimentation and variation. Many bodies were prepared chiefly by evisceration and then having a coating of molten resin applied. These bodies are often shiny and black, and look rather as though tar - bitumen- had been used. During the Roman period, bodies sometimes had gold leaf applied to the skin, and some mummies from this period, particularly those from the Oases, were well preserved by the natural climate. However, many beautifully wrapped corpses turn out to be mere collections of bones when x-rayed. Artificial mummification gradually died out in Egypt as the old religion which believed that the preservation of the body was essential was replaced by Christianity and Islam.

The Ka, the Ba, and the Akh

Over the course of their three millennia of culture, the Ancient Egyptians developed many complex ideas about humanity. Western European culture often divides the person into body and soul. Modern psychology divides the person in other ways, using terms such as ego, id, and superego, or animus and anima, persona and so on.

There are seven, or perhaps nine, elements to the human being in Egyptian thought: the name, the heart, the corpse or body, the shadow, and three spiritual elements called the ka, ba, and akh. Two other elements, the sekhem which is the individual's ability to control his faculties, and the sakhu which refers to a person's social status in this world or the next, are sometimes considered. No one knows to what extent ordinary Egyptians thought about the many theoretical divisions of the being. The is good evidence, though, that at least to the level of craftsmen, people did believe in the existence of the Ka, Ba, and Akh.

The Ka

The idea that some part of the human personality survived death is a very ancient one in Egypt. Many kings formed their names with the element ka: for example, Menkaure and Shepseskaf of the Fourth Dynasty. Ka was also a common element in non-royal names. The hieroglyphic sign for ka shows two arms, palms open, outstretched. The word ka has associations with food, with bulls, and with the soul, the spirit or essence of a human being.

Every person, rich or poor, man or woman, had a ka. It was the life force, the element that made the difference between a living person and a dead body. At death, the body and the ka were separated. In order to enjoy eternal life, they had to be reunited.

The ka was a spiritual entity, but it needed food to survive. This food could be in the form of real offerings, or it could be images or even words. Inscriptions on tombs from the Age of the Pyramids often ask passers-by to say a prayer - "May this official be given a thousand loaves of bread, a thousand jugs of beer," because the words would be enough to feed the ka if no tangible offerings were available. The written prayers, as well as the pictures and the appeal to the living, were all required if the ka was to survive. The ka could inhabit a human body, or a statue. The images found in serdabs are ka statues, able to replace the body of the deceased if it should be destroyed. The ka needed a recognizable form to dwell in; without it, the ka might cease to exist.

The Ba

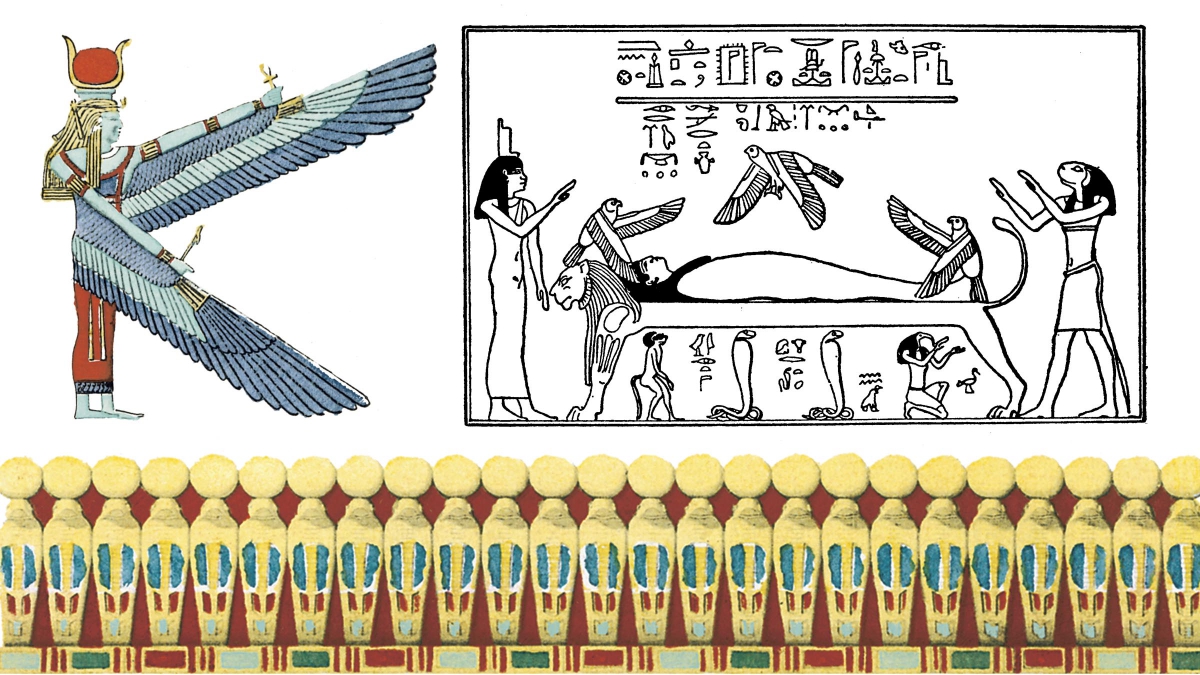

The ba is another spiritual entity. In the Age of the Pyramids, it was thought that only the King had a ba. The word ba was similar in sound to the word for 'ram' and seems to have connotations of power and strength similar to that animal. Unlike the ka which had to stay near the body of the deceased, the ba could move above, even fly. In later periods of Egyptian history, every person was believed to have a ba. The Ba is often shown as a human-headed bird, flying over the motionless body of the deceased, or exiting the tomb.

Some charming images from Ramesside Books of the Dead show the Ba perched on the arm of the deceased, or hugged to his body, like a pet parrot. the small pyramids built over the tomb chapels at Deir el Medina contained a little niche near the top, where the Ba could perch, to watch the sunrise, and to observe the goings-on in the village where it had lived. Like the Ka, the Ba reacquires food. The Ba wants to move, eat and copulate forever.

The Akh

An akh is yet another spiritual entity. Every good person who died and was buried in 'hallowed ground' in the official cemeteries, became an akh. This word was used, as far back as the First Dynasty. An akh is the blessed or 'transfigured' soul of a person who died and whose soul had been judged by Osiris and found maat kheru - justified. An akh was an effective spirit, one would could still influence events in this world. It is because he has become an akh that Metjetji can promise to help anyone who prays for him:

As for any servant or any man of my funerary estate who will come to offer to me [and give me bread], I will let him see that he recognizes it is useful to offer to a spirit (akh) in the necropolis.

Condemned criminals were not permitted a proper burial, and their real names were stripped from them, so that they could not survive in the Afterlife. An evil-doer could not become an akh. Thus, criminals were condemned in this life and in the next.

Both the Ka and the Akh required a tomb and a preserved body in order to survive. The Ancient Egyptians took this requirement very seriously. When the explorer Mekhu died on active service in Nubia, his son Sebni took a troop of men and a hundred donkeys loaded with trade goods, and located his father's body and brought it back to Egypt for mummification and burial. When King Pepy II learned of Sebni's filial piety, he sent a letter by royal courier:

It was said in this command, "I will do for thee every excellent thing, as a reward for this great deed; because of thy bringing thy [father].

Death did not break the bonds between the living and the dead. The living had a duty to help those who had gone before them, and to those who would come after, by building and maintaining tombs. Tombs were the interface between time and eternity.

Maat Kheru

Maat is an ancient Egyptian word meaning 'justice' and 'balance.' At the end of a civil trial, one party or the other was declared maat kheru, 'true of voice' or 'justified.' After death, each Egyptian expected to face a trial in the next world. In the final phase of this trial, the heart, the seat of intelligence and moral judgment as well as of emotions, was weighed against an ostrich feather that represented Maat, the goddess of Truth and Justice. If the heart balanced, against the feather, the person had lived a good life, and could enter into the Afterlife. If the heart did not balance, a monster called The Devourer consumed it.

The weighing of the heart is a common motif on coffins of the Late Period, and can also be seen in Books of the Dead. The Devourer was considered too dangerous to be seen on coffins, though she does make an occasional appearance on them in Ptolemaic times.

Burial Customs

We know nothing about the funerals of ordinary people, but the decoration in Old Kingdom tomb chapels tells us a little about the funerals of nobles. The Pyramid Texts and the layouts of royal mortuary temples give us some idea about rituals surrounding the death of the king. Although there were changes to this ritual over the next two thousand years, the changes were surprisingly minor. Evidence from the New Kingdom and Late Period suggest that the rituals that had once accompanied only kings and nobles later were performed for small landowners and craftsmen. How were the masses, the farmers, taken to their eternal rest? We do not know, but the Middle Kingdom text, The Dispute of a Man with his Ba, offers a sad image of the resting place of the very poor.

Those who built in granite, who erected halls in excellent tombs…their offering stones are desolate, as if they were the dead who died on the riverbank for lack of a survivor.

In the Late Period, the story of Setne Khaemwase and Sa-Osiris offers another thought about the burial of the poor. Prince Khaemwase looks out of his window and saw the rich funeral of one man, and the pathetic lack of ceremonies of another. Saddened at this sight, he is reassured by his son, Sa-Osiris who takes him on a tour of the Underworld:

My Father Setne, did you not see that rich man, clothed in a garment of royal linen, standing near the spot where Osiris is? He is the poor man whom you saw being carried out from Memphis with no one walking behind him and wrapped in a mat. They brought him to the netherworld. They weighed his misdeeds against the good deeds he had done on earth. They found his good deeds more numerous than his misdeeds in relation to his lifespan, which Thoth has assigned him in writing, and in relation to his luck on earth. It was ordered by Osiris to give the burial equipment of that rich man, whom you saw being carried out from Memphis with great honours, to this poor man, and to place him among the noble spirits, as a man of god who serves Sokar-Osiris, and stands near the spot where Osiris is.

Soon after death, the body was taken to the wabet, the 'pure place,' where the embalming actually was carried on. This appears to have been a tent, away from residential areas, on the edge of the desert. The dry heat of the desert air and the sun pounding down on the linen roof would have speeded the drying process. Drying and wrapping took about seventy days. The formal mourning period may have coincided with the embalming. During the New Kingdom, the process of mummification began in the Per-Nefer - the House of Beauty.

The tomb of Ankhmahor shows the body of the tomb-owner being taken from his own home, amid much weeping. Two women play the roles of the goddesses Isis and Nephthys; they are called the djeret mourners. The women who performed these parts may have been professional ritual practitioners, or members of the family. Tombs of the Nobles, and even of the Craftsmen of the New Kingdom, show the same ritual djeret mourners, who may have been family members or professionals, hired for the event.

The body was ferried across the Nile from the East Bank, where the living dwell, to the West, the land of the Dead. The coffin would then be dragged on a sledge from the water's edge to the tomb itself. In the case of kings, the mummification may have been carried out in the Valley Temple, and the body then dragged up the Causeway to the Mortuary Temple at the base of the pyramid. Craftsmen performed the funeral ceremonies for their friends, and seem to have carried the mummified body to its tomb, much as pallbearers carry a coffin.

In front of the tomb, lector priests read out prayers, and burned incense before the coffin and the ka statues. For kings, there would be dancing and singing by priestesses, and sacrifices of animals. Richer nobles probably had similar ceremonies, on a smaller scale. Singers and dancers could be hired for such occasions.

A procession carried the wordily possessions of the dead person to the tomb. Considerable amounts of cloth, cosmetics and furniture, as well as the traditional food offerings were placed in the tomb.

Finally, when the coffin was in its place, a ritual practitioner would perform the Opening of the Mouth ceremony, probably on the ka statue, to enable the dead person to see, hear, breathe, eat and speak again.

One of the last acts of the ritual practitioners would be to sweep footprints from the floor of the burial chamber.

The final part of a funeral was a funerary banquet, (perhaps somewhat like an Irish Wake) at which the relatives and friends of the deceased, sure that everything possible had been done for the safety of their loved one, could relax a little, and remember the good times.