New Research from the Burgess Shale: Thorny worms that swarmed in the Cambrian seas

Hallucigenia sparsa is no ordinary animal. This poster child of the Burgess Shale biota is the ultimate weirdo, and the ROM holds the world’s largest collection of specimens.

New research published July 31st in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series B, provides fresh new revelations about this fascinating creature.

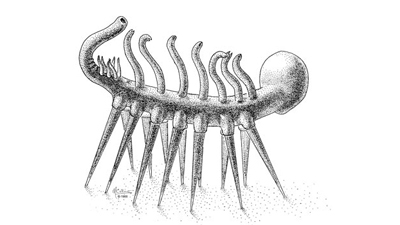

Hallucigenia was originally described as a creature walking on sticks (above). Drawings from the time showed a tubular body supported horizontally on what looked like sets of stilts.

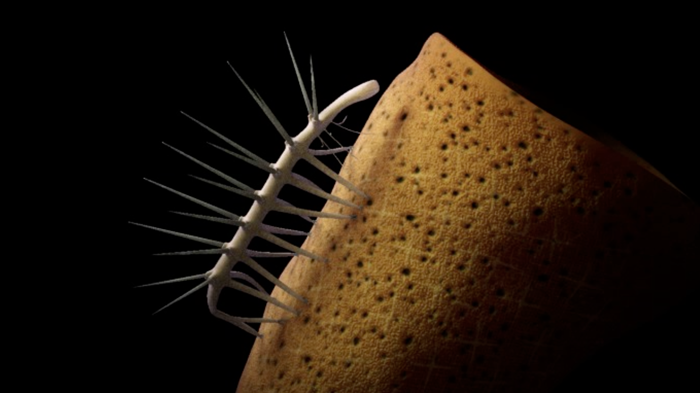

This idea of how Hallucigenia looked was literally turned upside-down when pairs of bona fide legs equipped with sharp terminal claws on its other side were discovered. The legs, now visualized as facing down, were previously thought to be some sort of feeding tentacles projecting vertically above the body in the search for food. In this new portrayal, the “walking sticks” were reinterpreted as lethal defensive needles to ward off predators that might have been interested in snacking on Hallucigenia’s otherwise soft body parts.

Don’t be alarmed – this animal is thankfully, well, really tiny – no longer than an eyebrow. It lived 505 million years ago in a long lost world, before plants or animals lived on land, when the biggest creatures known lived in the oceans. Today’s closest relatives to Hallucigenia are the velvet worms. Unlike their spiny Cambrian ancestors, velvet worms have lost all their defensive spines and plates. Evidently these structural defenses became useless during the course of evolution, but when the modern forms lost these features is unknown. Modern velvet worms, or onychophorans, as they are commonly called by scientists today, live exclusively on land, in tropical forests. They are nocturnal ambush predators, lurking among decaying trees and feasting on arthropods and other small preys they trap with sticky slime shot out of glands near their mouths. By contrast, Hallucigenia might have lived on sponges or decaying matter on the sea floor. See also the Burgess Shale website.

It turns out that Hallucigenia had many close relatives all over the world during the Cambrian period, a fact that eluded scientists for decades. Even the species name, “sparsa,” means rare. So how did we figure out that this animal was, in fact, quite common, and had a much bigger family tree than was previously thought?

The problem, if we can find one with the Burgess Shale, is that few sites in the world preserve soft-bodied organisms. Because Hallucigenia was entirely soft-bodied, it had few chances to be preserved under normal conditions. The only exception was its spines, which are slightly more robust than the rest of the body. But even though the animals in the Burgess Shale are preserved exceptionally well, it is still only one site, representing only one place and period of time. Looking at only one site alone does not provide enough information to learn about the spatial distribution of species during the Cambrian period more broadly, or exactly when an animal like Hallucigenia might have first evolved.

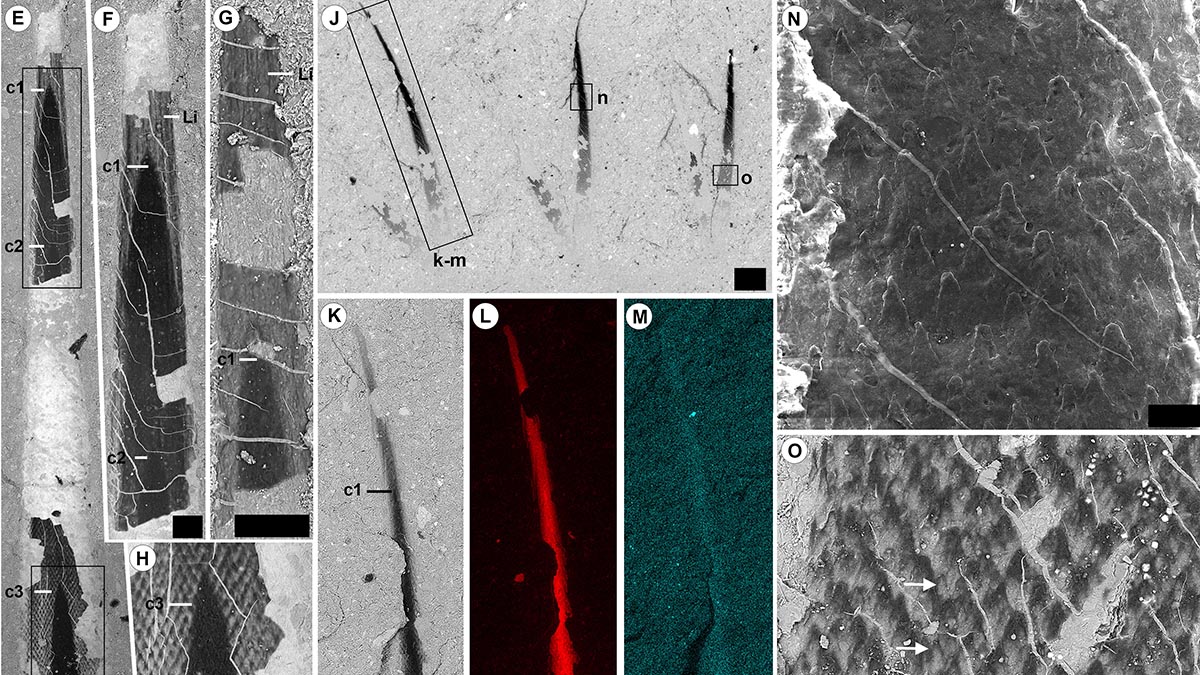

What we discovered was fairly serendipitous. Using a powerful microscope called a scanning electron microscope, we saw that the spines of Hallucigenia had tiny little projections on them that formed specific and unique patterns. The spines were also constructed like a stack of ice-cream cones, with the sharp end pointed upwards.

Similar spines had been discovered all over the world in fossil sites where soft-bodied animals were not preserved. At these sites, only tiny bits and pieces of tough or mineralized body parts withstood the fossilization process (to learn more follow link). Most of these disassociated spines found at those sites remained mysterious even to paleontologists – they did not seem to belong to any known creature. In fact, nobody had a clue what these spines were before our discovery. However, because sites with these microfossil spines are relatively common, they had provided information on the distribution of species during the Cambrian period. Now that we know the spines belong to Hallucigenia or its closest relatives, we are able to piece together Cambrian ecology in even more detail.

This story emphasizes the complementary role that different types of fossil deposits can bring to our understanding of life on our planet. It also shows that, despite its exceptional preservation of soft-bodied animals, the Burgess Shale does not provide answers to all questions!

This story emphasizes the complementary role that different types of fossil deposits can bring to our understanding of life on our planet. It also shows that, despite its exceptional preservation of soft-bodied animals, the Burgess Shale does not provide answers to all questions!

What’s next? Well, we still have lots of work to do. For instance, we still do not know for sure which end of Hallucigenia is the front and which is the back! A full redescription of Hallucigenia is currently underway, thanks in large part to the fantastic Burgess Shale collections at the ROM – the world’s largest. Surely there are more discoveries to be made, and this little critter has not yet finished surprising us. Stay tuned for more news!

Research paper reference: Caron J.-B., Smith M., Harvey T.H.P. 2013 Beyond the Burgess Shale: Cambrian microfossils track the rise and fall of hallucigeniid lobopodians. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences First published online July 31st, 2013.

A press release about this new research can be found in the ROM’s Newsroom.

See also a National Geographic article by Ed Young: "When hallucinations walked the world"

Jean-Bernard Caron, Curator of Invertebrate Palaeontology (links to bio page; research page)

To learn more about the Burgess Shale location in Yoho National Park and they mysterious creatures that were fossilised there, visit the interactive multimedia website developed by the ROM and Parks Canada. http://www.burgess-shale.rom.on.ca/