Minding the Stores

Guest blog by Lance McMillan

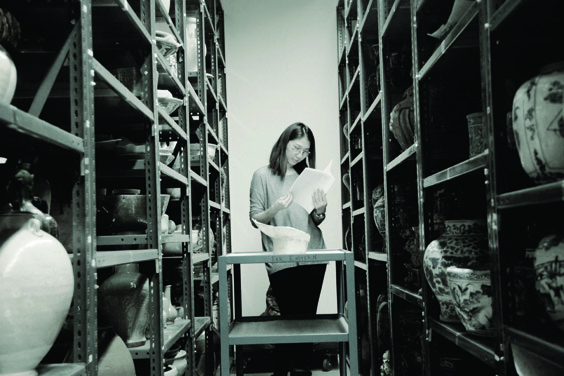

The ROM’s extensive collections are lovingly watched over by an expert team of dedicated curators and technicians.

With approximately 60,000 artifacts in the Royal Ontario Museum’s East Asian collection, managing this volume of items can be a daunting task. While some of the pieces are large and sturdy, like the Ming Tomb in the Gallery of Chinese Architecture, most are not. The delicate nature of the more fragile objects demands the utmost care and handling in order to preserve them— and the histories they represent.

At the ROM, a dry room is kept at a low humidity, approximately 25 percent, for the storage of certain metal artifacts, primarily those made of bronze. In contrast, a wet room with a higher humidity is used for storing objects made of lacquer and wood. The better part of the collection, such as ceramics, jades, prints, and bones, is kept in the main storage room at ambient temperature.

The use of acid-free materials, either pH-neutral or alkaline-buffered, further helps create a proper storage environment, increasing the longevity of the objects. Acid-free paper and boxes are used to separate and store prints. Acid-free foam cushioning safeguards smaller artifacts and props up larger ones, such as samurai armour chest plates.

While many safety measures are taken for the physical care of these objects, this is not the only means of preservation taking place. One of the ROM’s current projects is the digitization of its collection, which will make more artifacts and specimens available online. For the Asian collection alone, this will be an extensive process, particularly the cataloguing of the oracle bones—fragments of tortoiseshell and animal bone (even the occasional tiger bone and human skull) once used for pyromancy, a form of divination.

More than Bones

Oracle bones in the ROM’s collection number almost 8,000—the largest assemblage outside of China—dating back more than 3,000 years to the Shang Dynasty. These fragments, some less than a centimetre long, have to be measured and photographed, as well as rehoused, having been sitting loose in cotton-lined drawers since the 1980s. This process involves cutting out precise pockets of acid-free foam for each one. Like all acquisitions, they also have to be recorded in the Museum’s database, an exhaustive index that includes information about all objects and their donors as well as the curators’ reasons for collecting them.

On top of displaying artifacts through exhibitions and permanent galleries, the ROM also produces many publications that showcase its collections to the public. While a new book documenting the collection of oracle bones is years down the road, a book highlighting the Museum’s collection of more than 1,400 Chinese jades is planned for release later this year. Presented in both English and Chinese, it will be co-authored by Chen Shen, Senior Curator and the Bishop White Chair of East Asian Art and Archaeology, and jade specialist Gu Fang.

Projects like these will continue to arise because the ROM is constantly receiving new acquisitions, primarily from donations and bequests. The largest acquisition last year was a donation from York University Professor Emeritus Balfour Halévy of more than 600 artifacts, the bulk of them prints by the 19th-century Japanese artist Ogata Gekkō, making the ROM one of the largest collectors of this artist’s work in the world.

In addition to the quality of an object (one of the most significant factors curators consider when screening possible acquisitions), it’s also key to determine the object’s effectiveness at filling any gaps in the current collection. They need not be relics either, as was the case with the recent addition of a monkeyengraved teacup made by the noted Japanese potter Rakusai Takahashi for the Year of the Monkey. One of reasons this cup is significant is that it contributes to the ROM’s small collection of Shigaraki pottery.

With new acquisitions through donations, curators first need to answer some questions: Do the objects have cultural significance? Are they authentic and of sufficient quality? Do they fall in line with the ROM’s comprehensive acquisition policy? And finally, is there enough space to store them? One of the setbacks of having such an impressive collection is that space has become increasingly limited.

Taking in and caring for artifacts is a never-ending endeavour at the ROM, and each day is different. The process is a painstaking, careful one that takes time. But, it’s the best way to ensure new objects are authentic and can be properly stored, preserving their stories for years to come.

Originally published in the Summer 2016 issue of the ROM Magazine.