Go with the Flow: Technology & Early Glass

Glass is probably the most fluid of solids. Looking at blown glass, such as that in the ROM's Chihuly exhibition, is like watching movement made still. If you look carefully at the handles of the perfectly preserved handles of this Roman glass vase from Syria (above), it looks as though it is still a fluid, still dynamically moving along its flow. In a way, that is because it is. Glass essentially has the atomic structure of a fluid, but it has been so rapidly cooled that it is essentially stuck in that condition.

The face of an ancient glassmaker? Bead in the form of man's head with beard and hat, Glass, multicoloured, formed around a core of sand, Phoenician, c. 400-300 BC, ROM# 2000.106.420 - Gift of Joey and Toby Tanenbaum, Height 2.5cm Width 1.3cm Depth 1.5cm

Ancient glass is primarily made of silica. A typical ancient glass was made of about 75% silica, 10% calcium oxide or lime, and 15% sodium carbonate, or soda. The silica will have come from quartz-rich sand or crushed stone, the lime may have been added or naturally occurring in the sand as shell. The soda will have come from plant ash. Quartz melts at 1670 °C, and so the soda acts as a flux that helps the quartz melt at a lower temperature (Canadians know of this effect when they put salt on solid water to help it melt at a lower temperature). The lime helps to stabilise the glass. Other elements may also be added to ancient glass: aluminium improves the chemical durability of the glass and prevents re-crystallisation; magnesium decreases the solubility of the glass, potash is also a common flux, making a glass which hardens more rapidly and at a higher temperature; while lead oxide as a flux makes a glass of lower softening temperature and high density.

Possibly the oldest fragment of glass in the ROM (photographed in the Egypt gallery), other fragments *may* be older, but this is from the reliably-dated occupation of Tell al-Amarna in Egypt, Amarna Period, 18th Dynasty, New Kingdom; c. 1352-1327 BC, 927.75.10 - Gift of Sir Robert Mond, Length 4.2cm Height 2cm

The preparation of ancient glass entails grinding all of the raw materials together very finely. The raw materials are not now melted together in very ancient glass, but are typically sintered or fritted together at about 750-850 °C for several hours. This slow process enables gases to escape from the mix. The resulting material, known as "frit", is then ground to a powder. This powder is essentially raw glass. By the 1st century BC the glassmakers actually melted the raw materials into glass. Glass must be heated again to a sufficient viscosity to be worked. Viscosity is measured in units of "poise". At a viscosity of 7.65 poise the glass is soft enough to be worked, and at a poise of 4.0 it is in a molten state, so glass is typically worked between these states. For ancient glass that would be typically between about 690 and 1000 °C.

This cup is made of blown glass with trailed decoration, gas bubbles or "seeds" may be seen in the body. Syria - Mediaeval Period - 7th-8th century AD, ROM #926.11.1 - height 6.3cm diameter 6.4cm

It seems that the earliest evidence for all developments in ancient glass production may be found in the Levant or Greater Syria, comprising the modern countries of Lebanon, Western Syria, Israel, Palestine, and the Hatay province of Turkey around Antioch. The earliest glass object is a bead found on the site of Tell Judeidah in Hatay, dating to the 3rd millenium BC. Later in the 3rd millennium rare glass beads are known from a handful of sites across Mesopotamia, but it seems that in contemporary texts the words used for glass are from the Western Semitic region (i.e., the Levant). These beads are formed by rolling the soft glass around a straight rod.

This rod-shaped bead is actually from about 1200 BC, but the structure of it shows the same technique as on very early glass beads, with semi-molten glass wrapped around a rod. From Tchoga-Zanbil, Iran, Elamite Period; c. 1200 BC, 961.176.8.A-B, length 4.8cm diameter 1.5cm.

The earliest glass vessels are found again in Hatay at Tell Atchana (ancient Alalakh) of the 16th century, and were part of a glass bead industry that was known across the region. It is really only at this time that glass becomes a significant part of the archaeological record. These early vessels were made by making a core of clay wrapped around a rod. Semi-molten glass was then attached and wrapped around the core and when the glass was cold the clay core would be broken out. Many important glass-working techniques were already present in this period, for instance "trailing" different coloured glass strands across the vessel and "marvering" the vessel by rolling it on a hard surface to shape it. The glassmakers also used the techniques of stonecutters to cut glass when it was cold. However, it is thought that this was all made for the elites of society.

This small bottle was formed around a clay core, then when it cooled the core was gouged out, and the bottle was cold-cut on a grinding wheel Found in Egypt, probably Fustat - Mediaeval Period - 9th-10th century AD - ROM #950.157.68 - Gift of Miss Helen Norton - height 8.9cm diameter 2.1cm. ROM Photography.

In the first century BC, possibly in Sidon in Lebanon, glassmakers discovered that by sticking a hollow tube into molten glass and blowing it, you could make it expand and thus cheaply make numerous vessels. Across the then Roman world blown glass became a popular item for much of society.

Blown glass, whether free-blown or blown into a mould (like the pieces on the far left and right) became very popular across the Roman world, and became the staple of the table that it is to this day. All of these are from the Roman Imperial period (about the 1st century AD) and were probably all made in the Levant (Syria or Lebanon). ROM Photography.

This bowl was first blown and tooled to shape, then white glass was trailed onto the surface, then excised off, the surface was then marvered to make the decoration flat. Made in Egypt or Syria - Mediaeval Period - 12th-13th century AD, ROM #951X8.125 - height 6.5cm diameter 13cm. ROM Photography.

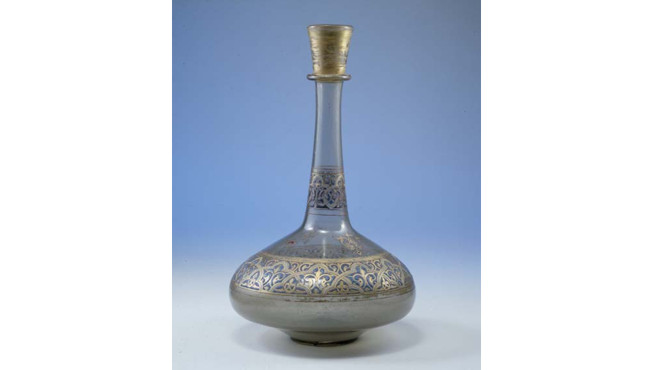

During the Islamic period the glassmaker's most desirable creations were of enamel-painted glass, probably starting in Syria in the early 13th century. In the 15th century Venice became the most important centre for this type of glass. Enamelling entails application of paints containing powdered coloured glass. After painting, the object is heated up again so that the paint becomes fluid and fuses to the body, but not to high enough a temperature for long enough that the body of the glass flows and deforms.

This bottle, of blown glass with enamelled decoration, was probably made in Syria, but was found in a mosque in Shanxi province, China. Blown glass was as mysterious and miraculous to the Chinese as porcelain was in the west, and vast amounts were transported to the East. Ayyubid Period - early 13th century AD, ROM #924.26.1 - The George Crofts Collection - Height 27.2cm Diameter 5.7cm. ROM Photography.

Ancient glass often has a distinctive patina. The surface of the glass reacts with the water in the soil in which it was buried to form very fine corroded layers When light bounces from the surface of these sheets, it creates the iridescence often found attractive in ancient objects, but which were not a part of the original object.

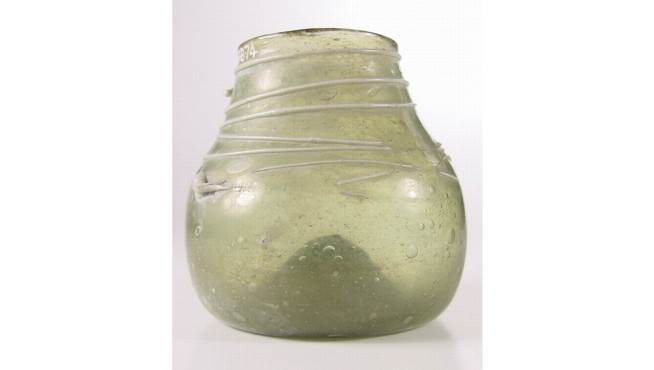

This vessel of blown and trailed glass has had its surface weathered. This is not a layer that has formed on the exterior, but actually *is* the exterior of the vessel turned into sheets. Where this has been removed in the past you can see the original colour of the glass, but the actual surface of the original vessel has been removed in order to see it. Syro-Palestine - Roman Imperial period - c. 350 to 425 AD, ROM #950.157.102 - Gift of Miss Helen Norton - Height 12.8cm Width 6.2cm Diameter 5.2cm. ROM Photography.

This jar was originally blown in transparent glass. The iridescence visible on the surface is due to the glassy structure reacting with the water in the soil in which it was buried to form very fine corroded layers. Levantine, Roman Imperial period; 175-300 AD, ROM# 950.157.240 - Gift of Miss Helen Norton, height 10cm diameter 6.6cm . ROM Photography.

So do come to the ROM and see the glass, in the Chihuly exhibition and in the galleries. And next time you are having a glass of water, think about the long history of that humble receptacle. A technology of fire and sand from the shores of the Levant.

Acknowledgements:

I'd like to thank my friend and colleague Dr Ian Freestone for valued input into this blog, and to Dr Kay Sunahara for pointing out the shiniest glass in the Greek & Roman collection.

Links:

Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Gallery of Rome and the Near East - excellent collection of Roman glass

Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Gallery of Byzantium - some very nice glass

Wirth Gallery of the Middle East - gallery covering the homeland of glass

Galleries of Africa: Egypt - some of our earliest glass on display

Corning Museum of Glass: Origins of glassmaking

MMA Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: Roman Glass